When a landlocked country loses reliable access to its nearest sea gateway, the effects ripple through prices, jobs, food security and state revenues. Over the last few weeks, Afghanistan has experienced precisely that shock: multiple Afghan-Pakistani border crossings have been closed amid security and diplomatic tensions, and Kabul has publicly accelerated plans to reroute trade through Iran and Central Asia. The closures sharpen an already fragile economic picture, modest growth, a widening trade deficit, acute food insecurity, frozen foreign assets, and limited formal banking, and force Kabul to choose between urgent stopgaps and longer-term structural changes. This article maps the current state of Afghanistan’s economy, explains the economic consequences of the near and medium term, and offers a practical prognosis and policy priorities for the next two years.

Snapshot: Where Afghanistan’s Economy Stands Now

After the shock of 2021, Afghanistan’s economy has shown fragile recovery signs: World Bank estimates point to modest GDP growth (around 2–2.7% in 2024), driven mainly by agriculture, construction and commerce, but the rebound is uneven and dependent on a narrow set of sectors. Core weaknesses are persistent: a large and growing trade deficit, low fiscal revenues, limited foreign exchange reserves, constrained formal banking, and a massive humanitarian shortfall — with millions facing acute food insecurity and rising child malnutrition. The country remains heavily import-dependent for food, fuel, medicine and industrial inputs.

The World Bank’s monitoring shows Afghanistan’s trade deficit widened substantially in early FY2025: imports surged while exports remained narrow, and the Afghani’s exchange movements have not restored competitiveness. At the same time, formal cross-border flows with Pakistan — historically one of Afghanistan’s largest trading partners and the quickest route to sea via Karachi — have fallen sharply from pre-2024 levels, increasing pressure on logistics and prices.

What Just Happened at the Pakistan border and Why it Matters

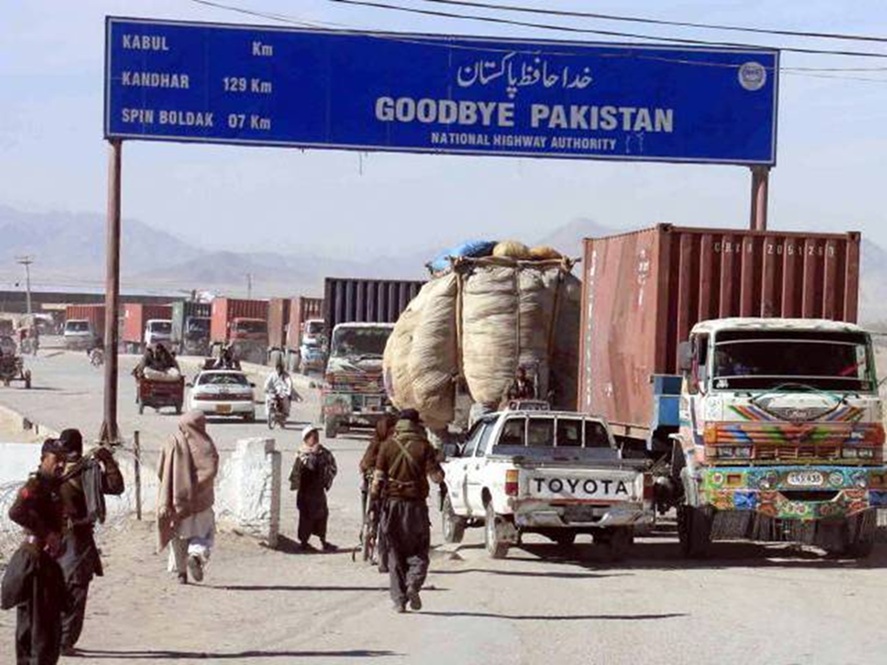

In recent weeks, Pakistan closed several key transit crossings (including Torkham and Spin Boldak at various times), citing security concerns; Afghanistan’s authorities say closures are political and punitive. Whatever the proximate cause, the immediate economic impact is simple and large: daily trade flows for vital consumer goods, construction material and industrial inputs have been delayed or redirected, informal trade channels have surged, and traders are reporting losses running into the millions of dollars. Pakistani exporters and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa businesses also face losses, but for Afghanistan, the cost is disproportionate because alternative sea access is longer, costlier and logistically more complex.

Bilateral trade had already fallen from its peak: recent Afghan ministry figures show trade with Pakistan moved from nearly $2–3 billion in earlier years to about $1 billion in the first half of 2025 — a sharp contraction that magnifies the effects of any new closures. Reduced access to Karachi removes the shortest sea channel for imports and exports and increases transit costs for everything from rice and pharmaceuticals to construction steel.

How Afghanistan is Re-routing Trade — Practical Pathways and Limits

PC: Dawn

Kabul has publicly accelerated plans to diversify transit routes. Three options are now central to immediate and medium-term strategies:

Iran — Chabahar and Bandar Abbas. Iran’s Chabahar (India-supported) and Bandar Abbas ports are the most viable sea alternatives. Chabahar offers a political and logistical corridor to the Indian Ocean without reliance on Pakistan; India has invested in Chabahar precisely to provide an alternative transit for Afghanistan. Recent reporting indicates Afghan trade through Iran rose sharply in late 2025, with reported trade volumes in the past six months surpassing trade with Pakistan in some measures. Iran is offering incentives (reduced tariffs, storage, improved processing) and is geographically closer to seaports than the Central Asia routes. However, Iranian transit is subject to Tehran’s sanctions exposure, seasonal connectivity issues along the Afghan-Iran borderlands, and a capacity gap in overland links inside Afghanistan.

PC: Newsline Institute

Central Asia — Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan. Northern corridors through Turkmenistan (to Turkmen ports and then Russia/Black Sea markets) and Uzbekistan/Tajikistan (rail and road to Central Asian railheads) are expanding. These

routes benefit from growing overland rail capacity and Central Asia’s interest in connecting to South Asia; they are politically stable compared with the volatile Pak border. Still, transit distances grow, costs per container rise, and rail/road bottlenecks at Afghan transhipment points require investment. For bulk exports (minerals, some agricultural commodities), Central Asia corridors are promising in the medium term.

China corridor and Wakhan option (long shot). A high-altitude corridor through the narrow Wakhan strip into Xinjiang is technically possible for select mineral exports and small high-value cargoes; however, it still faces enormous infrastructure, security and cost constraints. It is not a substitute for short-term mass consumer imports or for food security supplies.

Air and Regional Hubbing. Air corridors can move high-value or urgent goods (medical supplies, parts), but the cost per kilogram makes air freight impractical for staples. The government and private traders will rely on a mix of air for urgent cargo and overland routes for volume items.

In short, rerouting is happening — but it is costlier and slower. Iran and Central Asia offer alternatives; they reduce Pakistani leverage but cannot immediately reproduce the speed, cost structure and volume capacity of Karachi without investment and international cooperation.

Immediate Economic Effects (Weeks to 6 months)

Higher consumer prices. Supply disruptions and longer routes raise freight and import costs; food and fuel prices will feel the shock first. With already fragile household incomes, inflationary spikes risk pushing millions into deeper food insecurity. Humanitarian agencies have already warned of worsening malnutrition.

Revenue and fiscal pressure. Customs and transit fees are a major source of state revenue. Disrupted crossings and informal smuggling reduce formal revenue and increase budgetary pressure — at a time when donor grants remain constrained and central bank access to reserves is limited. The World Bank has recorded widening trade deficits; reduced customs receipts worsen the fiscal gap.

Supply-chain strains and industrial slowdowns: Firms that import raw materials (textile inputs, chemicals, construction steel) will confront shortages or higher prices, delaying projects and causing layoffs. Informal trade channels expand, weakening formal regulation and safety standards.

Social and political stress: Border closures rapidly create local humanitarian pressures in border provinces and may spur migration or increased informal cross-border movement, complicating local governance and security.

Medium-term Dynamics (6–24 months) — Pivot Window

If closures persist beyond a few months, strategic shifts will solidify:

Modal shift solidifies: Private logistics firms and traders will invest, wherever possible, in the longer-term contracts with Iranian and Central Asian partners. India’s involvement in Chabahar and occasional U.S. sanction waivers make Iran a more credible partner. Over time, a nascent northern corridor network could handle more exports (minerals, dried fruits, cotton), but it will still struggle to handle consumer import volumes.

Higher structural costs and slower growth. The substitution of routes raises the logistics bill for Afghanistan. With import costs higher and external financing limited, GDP growth is likely to remain modest (low single digits) and unevenly distributed. The World Bank’s April–August 2025 updates suggest growth but growing vulnerabilities — a pattern likely to continue if transit instability persists.

Opportunities for export diversification: Forced changes create incentives to develop export sectors that are competitive via northern and Iranian routes: minerals (if responsibly and transparently managed), processed dried fruits, certain high-value agricultural products, and transit services for Central Asian trade heading south. Realising these opportunities requires legal clarity, investment in transport infrastructure, and reforms that attract partners.

Key Constraints and Downside Risks

Financial and banking bottlenecks. Afghanistan’s access to global banking, correspondent accounts and frozen reserves remains constrained. Without reliable cross-border payment rails, much trade will be cash-based or rely on informal hawala systems, increasing costs and corruption risk. This constraint limits the scale of any rapid rerouting.

International politics and sanctions. Iran-based routes expose Afghan trade to the geopolitics of sanctions and Western policy choices. While temporary waivers (e.g., to keep Chabahar operational) are possible, they are fragile and politicised. Relations with Central Asian states depend on Russian and Chinese regional strategies.

Infrastructure and security gaps. Road, rail and port capacity on alternative corridors is not yet sufficient for full substitution. Fragile security along internal transit routes (banditry, local conflicts) will raise insurance and freight costs.

Humanitarian crisis risk. Any sustained price spike or loss of imports — particularly of medicines and staple foods — risks deepening the humanitarian emergency. The WFP and other agencies already report critical nutrition shortfalls.

A Practical Prognosis (next 24 months)

Short term (0–6 months). Expect intermittent closures and partial re-routing. Price volatility for staples and fuel will be the immediate pain; customs revenue will fall, and fiscal stress will rise. Emergency humanitarian needs will climb unless donor commitments expand. Some traders will switch to Iran for urgent consignments, and air freight will see marginal upticks for high-value items.

Medium term (6–18 months). A new modal mix will stabilise: Iran-linked sea access (Chabahar/Bandar Abbas) plus Central Asian rail/road corridors will carry a meaningful share of Afghan trade. Overall trade costs will be higher (estimates vary, but add-ons of 10–30% for freight and handling are realistic, depending on the commodity). Growth will remain subdued; investment will be limited to projects with clear revenue payback or strategic partners (e.g., India on Chabahar; China on selected mineral projects). The domestic industry may contract for sectors dependent on cheap Pakistani inputs.

Longer horizon (18–36 months): If alternative corridors receive consistent international support and if Kabul can stabilise internal logistics and regulatory frameworks, Afghanistan could reduce dependence on Pakistan significantly. That outcome demands substantial infrastructure financing, normalisation of some banking channels, and a political environment conducive to investment. Otherwise, the country risks chronic higher import bills, weaker fiscal balances, and deeper humanitarian needs.

Policy Priorities — What Kabul and Partners Should Immediately?

Ensure humanitarian corridors for food and medicines with multilateral oversight to prevent shortages and malnutrition spikes. International organisations must be empowered to operate at scale.

Temporary trade facilitation agreements with Iran and Central Asian neighbours (fast-track customs lanes, joint checkpoints, storage incentives) to reduce delay costs. Iran’s port incentives should be matched with Afghan logistics support.

Temporary financial workarounds: Coordinate limited, transparent payment waivers or channels (multilateral escrow or trusted third-party clearing) to keep trade moving while limiting sanction risk.

Medium term (6–24 months)

Invest in transit infrastructure: Prioritise rehabilitation of road links to Iranian and Central Asian borders, container yards, and dry ports. Public-private partnerships and concessional finance (from multilateral development banks, India, or GCC partners) are essential.

Rail and intermodal development: Accelerate rail link projects with Uzbekistan/Turkmenistan and build dry-port capacity — these reduce per-unit costs for bulk commodities and gradually shift economics in favour of northern corridors.

Formalise trade and anti-smuggling measures. Closing informality will broaden the tax base and improve safety and standards — but requires credible enforcement and incentives for registration.

Structural (24+ months)

Export diversification & value addition: Process dried fruits, nuts and select minerals domestically to raise export value per ton and make northern and Iranian routes more profitable. Transparent, accountable mining contracts (with environmental safeguards) are necessary to attract long-term investors.

Banking and digital payments revival: Rebuild correspondent banking links (with international guarantees) and support digital cross-border payment pilots to reduce cash dependence and speed transactions.

Regional economic diplomacy: Afghanistan needs a concerted diplomatic push: tripartite arrangements (Afghanistan-Iran India; Afghanistan-Central Asian states; confidence building with Pakistan) to create durable commercial corridors and reduce politicised border closures.

How External Actors Will Shape Outcomes

Iran will be a key pivot. Its willingness (and ability, given sanctions and politics) to deepen Chabahar operations and coordinate transit rules is decisive. Iran already hosts ports and road connections that Afghanistan can leverage, but reciprocity and finance matter.

Central Asian republics (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan) have both the incentive and capacity to absorb more transit flows. Their investment in rail links and dry ports could turn Afghanistan into a functioning corridor, but they will insist on clear, enforceable transit agreements.

India has a strategic interest in keeping Chabahar viable (and has historically invested in it). Continued Indian logistical, technical and diplomatic support would accelerate Afghanistan’s ability to bypass Pakistan.

China and Russia could be both partners and competitors, offering finance for infrastructure (especially where their geostrategic corridors align with national interests). Their involvement will be governed by broader geopolitical calculations.

Who Should Finance the Transition?

A practical financing mix would include concessional loans/grants from multilateral institutions (World Bank, ADB, Islamic Development Bank), targeted bilateral investments (India in Chabahar, Iran in port logistics, Central Asian states in rail links), and private concessionaires for terminals and warehouses. Donors will demand safeguards (transparency, humanitarian protection, non-militarisation clauses) to justify support. The political risk premium is high; financing may require partial risk guarantees from third parties.

Bottom Line: Resilient but Costly Transition

The overnight closure of Pakistani transit lanes is a shock — but not an existential impossibility. Afghanistan can and is already rerouting trade toward Iran and Central Asia. The trade diversification trajectory is politically and technically feasible, but it is expensive, slow, and contingent on external finance, diplomatic cover (sanction waivers where required), and improvements in domestic logistics and governance.

Absent concerted international support to stabilise food and medicine imports and to underwrite the infrastructure shift, the next 12–24 months will be painful: higher prices, slower growth and deeper humanitarian need. With pragmatic, coordinated action — humanitarian prioritisation, rapid trade facilitation with Iran and Central Asia, targeted infrastructure investments, and creative financial arrangements — Afghanistan can trade and reduce Pakistan’s chokehold on trade and build a more diversified, if more expensive, trade map for the medium term. The political choice for regional actors is simple: help stabilise Afghanistan’s trade links and markets now, or absorb the human and fiscal costs later.

Conclusion

The blockage of Pakistan’s trade routes is a significant shock to an economy that depends on low-cost overland access. In the short term, expect supply disruptions, higher costs and a slowdown in growth. But the structural picture is not entirely bleak: Afghanistan sits at a crossroads, and alternative corridors — Chabahar and links through Central Asia — can be scaled up. The critical variables are political will, access to finance, rapid implementation of logistics reforms, and regional diplomacy.

If Kabul and its partners treat the crisis as a catalyst for durable diversification — investing in dry ports, streamlining customs and locking in transit agreements- Afghanistan can trade and could emerge with a more resilient trade architecture within 2–3 years. If, instead, political tensions persist and transit remains ad hoc and expensive, the country risks a deeper economic retrenchment: lower growth, higher poverty and a lost generation of export opportunities.

In short, the route to mitigation is clear on paper — diversify, modernise and integrate with Central Asia and Iran — but achieving it on the ground will require money, diplomacy and steadier governance than Afghanistan has had in recent years. The coming months will tell whether the trade shock is a temporary pain or the pivot that finally re-sculpts Afghanistan’s place in Eurasian commerce.

Title Image Courtesy: Bhaskar English

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and the Defence Research and Studies

Bibliography

Al Arabiya News. 2025. “Afghanistan Increases Trade via Iran as Ties with Pakistan Strain.” Al Arabiya English, May 2025.

Associated Press (AP). 2025. “Aid Agencies Warn of Rising Child Malnutrition and Worsening Food Insecurity in Afghanistan.” AP News, June 2025.

Reuters. 2025. “Afghanistan Shifts Trade Routes to Iran and Central Asia Amid Repeated Pakistan Border Closures.” Reuters, May–June 2025.

Reuters. 2025. “Afghanistan-Pakistan Trade Falls Sharply as Border Disputes Persist.” Reuters, July 2025.

Reuters. 2025. “Iran Offers Port Incentives to Afghan Traders as Regional Transport Dynamics Shift.” Reuters, April 2025.

TOLOnews. 2025. “Afghanistan’s Trade Volume with Pakistan Drops to $1 Billion in First Half of 2025.” TOLOnews, June 2025.

World Bank. 2025. Afghanistan Economic Monitor, May 2025. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2025. Afghanistan Development Update, August 2025. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2024. Trade and Transit Patterns in South and Central Asia. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Food Programme (WFP). 2025. “Afghanistan Hunger Outlook: Food Insecurity Snapshots.” WFP Situation Reports, March–August 2025.

UN OCHA. 2025. Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2025. New York: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

International Crisis Group (ICG). 2024. Afghanistan’s Regional Economic Dilemmas. Brussels: ICG.

Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2024–2025. Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Corridor Outlook. Manila: ADB.