China announced new BRI infrastructure projects which include a $1.6 billion expressway from Phnom Penh to Bavet located at the Cambodian – Vietnamese border

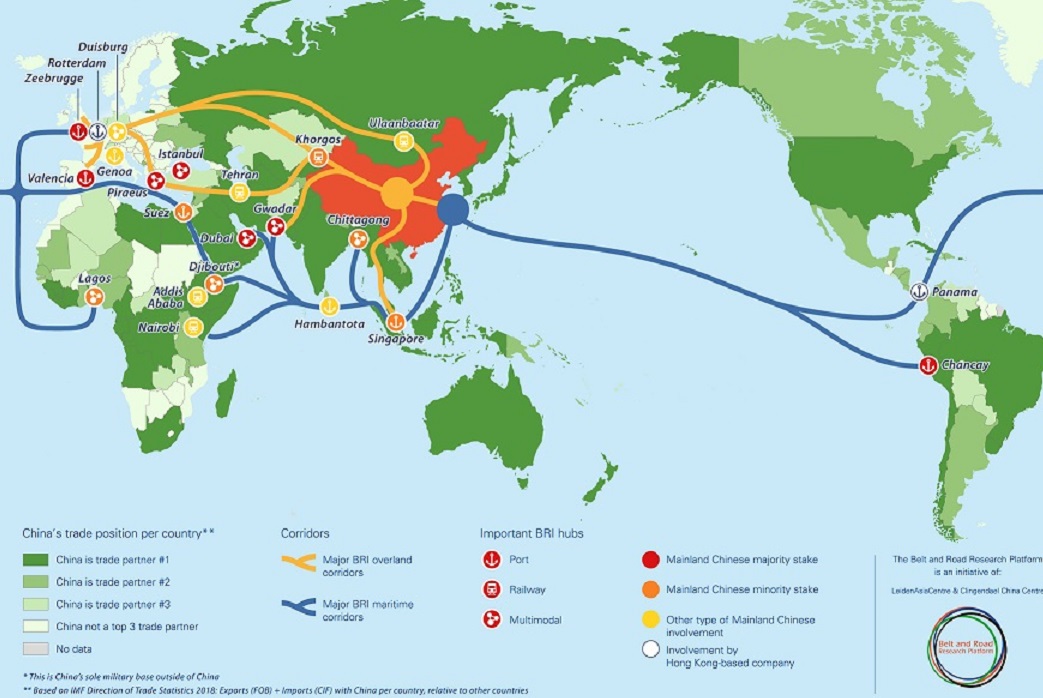

The One Belt, One Road plan, which was unveiled in 2013, is a geopolitical puzzle for the twenty-first century. It is said to be based on an early vision voiced by Premier Li Peng in 1994 during a trip to Central Asia. The project aims to capitalize on China’s extensive geographical ties with countries in Eurasia, as well as the significant economic benefits that such a huge area can provide, in order to advance China’s economic cooperation with Eurasian nations. The BRI envisions the construction of road and maritime connectivity between China and Southeast Asian, Central Asian, and European countries. China suggested two components as part of BRI: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road subsequently renamed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, its components are still evolving, revealing the development of Chinese interests around the world. As a result, the BRI has been expanded to include the “Digital Silk Road” which Xi Jinping introduced at the first Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing in 2017, and the “Polar Silk Road,” which aims to develop Arctic shipping lanes, as revealed in China’s Arctic Policy released in 2018. China is building a network of highways, railroads, ports, pipelines, electricity transmission lines, and communication cables across Eurasia through this Initiative. An overland Silk Road Economic Belt will connect western China to Western Europe via the Eurasian supercontinent, while a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road will cross the Indian Ocean, connecting the Western Pacific to the Mediterranean Sea. These programs also aim to improve unrestricted trade and investment flows, infrastructure and facility accessibility and quality, and financial and monetary cooperation. Many countries in the region are interested in this infrastructure development initiative since their poor transportation systems are a major impediment to their economic progress. The One Belt-One Road strategy can help to both expand China’s economic links with Eurasian nations and promote the economic influence of China in Eurasia as it is a reflection of the Chinese proverb that if you want to be rich, you must first build roads. This flagship project above all seeks to efficiently prop up Beijing‘s power in the whole of the Eurasian region. As experts have analyzed that the BRI is an aspiring geo-economic plan that is ordained to have a major influence on the economic system, either in a constructive way or in a negative way. The geo-economic competition is war by other means as Blackwill and Harris penned. Beijing has promised to invest billions of dollars in infrastructure and industrial sectors across Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific as part of the BRI. According to Rory Medcalf, an Australian analyst, the BRI is “the Indo-Pacific with Chinese characteristics”. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is China’s most ambitious geo-economic strategy in human history. This new policy appears to indicate that Beijing is eager to transform itself into a continental-maritime power. Furthermore, the Chinese Renminbi (RMB) will be marketed as an international currency, as the majority of funding raised for BRI projects will be raised through the issuance of Renminbi-denominated bonds, which will boost its use in global economic centres. There is no doubt that such a large investment will have substantial geostrategic consequences in zones where geopolitical competition between China and other major powers, primarily the US, is already escalating.

New political, trade and financial relationships will be forged as a result of this modern physical connectivity. According to former IMF economist Stephen Jen, the initiative amounts to 12 Marshall Plans. The fact is that China’s economic network is sweeping around the world, shifting the international power balance in such a way that even long-standing US friends in Asia are leaning toward Beijing rather than Washington. “China is dragging the Southeast Asian countries into its economic scheme because of its enormous market and expanding purchasing power,” writes Lee Kuan Yew. The use of Chinese economic strength can aid in the development of an Asian solution to an Asian crisis. In a move clearly meant to diminish the US role in Asian security, Chinese President Xi Jinping projected a new regional security vision centred on ‘Asia for Asians’ in his statement at the Shanghai Summit in 2014. It is up to the people of Asia to solve Asia’s challenges and uphold Asia’s security.

The focal point of Xi Jinping’s “proactive” foreign policy is the Belt and Road Initiative, spreading from the South China Sea across the landmass of Eurasia. As Xi Jinping put it, “when big rivers have water, the small ones are filled; and when small rivers have water, the big ones are filled”. China claims no control over the enterprise, which it says is about “mutual trust, equality, inclusiveness and shared learning, and win-win cooperation”, though, in actuality, it is very much a Chinese venture. The new BRI will connect more than 70 states, accounting for approximately 62% of the population of the world spread across Asia, Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Oceania. The BRI invited participation from all the countries in the world. A variety of broad objectives drive the endeavour. First and foremost, it serves to protect national security. China intends to build an economic dependency network that will help it to consolidate regional leadership, diversify energy supplies, and hedge against the US alliance structure in Asia. Xue Li argued that BRI allows the Chinese economy to be ‘open outside but not inside. The proposal is China’s second big overseas investment venture, following the “Go Out” policy in 1999 started by Jiang Zemin. It is certain that President Xi perceives the Belt and Road as a real step towards materializing the strategic objective of national rejuvenation; the “China Dream” and thereby protecting his own political legacy. Xi has smartly folded a number of existing or planned schemes into the grand narrative of the “Chinese Dream”, and made the Belt and Road crucial constituents of his geopolitical drive to build a Chinese-centered Asia. If the BRI thrives, it will result in “the enormous resurrection of the Chinese nation”. This strategy aims to solidify China’s primacy in Asia and develop a new zone of influence, similar to the Great Game of the nineteenth century, in which Britain and Russia fought for control over Central Asia. Zhang Yunling, director of international studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), has argued, “With its long-term interests in mind, China sees BRI as a magnificent initiative. As Yunling said, it might be called China’s “pivot to the West”. As Major General Qiao Liang noted, the BRI is a hedging strategy against the US ‘pivot to Asia’ eastward move or ‘rebalance to Asia’. So BRI can be viewed as Beijing’s geostrategic counterblow to the rebalance policy of the US. As, the US Pacific Command Admiral Harry Harris deemed in early 2018 that the BRI was “a determined, strategic venture by China to gain traction and displace the US and our allies and partners in the region”. The project also aims to make possible numerous people’s liberation Army Navy (PLAN) deployments in the Indian Ocean and afar. Through greater military/defence diplomacy, the Chinese think that the military should play a stronger role in defending the BRI. The PLAN needed reliable logistics chains across the Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOCs) throughout Southeast and South Asia. China wants “pivots” because it lacks the potential to construct a structure that would provide global coverage for the protection of its abroad interests, according to experts and observers. A pivot could be a country or a foreign base near a major port that can provide significant support to the BRI. The Chinese decision to build a naval facility in Djibouti (which Beijing refers to as a “supply centre”), located at the horns of Africa; and consolidate its influence in the port of Doraleh. Combined, China will be in a position to greatly restrict the US’s ability to operate in the region. Djibouti’s naval base could be a good example of the ‘pivot’ policy. Furthermore, despite multiple US attempts to sway Israel’s decision, China’s possession of the port of Haifa gives China a clear strategic advantage in the Mediterranean, as the US navy will no longer favour Haifa for repairs.

Analysts believe that the BRI will significantly impair the geopolitical interests of the US and serve as a terrible threat to the Pax Americana, particularly the US strategic position in Asia. The BRI is said to have the potential to ‘amend the global landscape, shifting the centre of strategy and commerce to the Eurasian continent from the adjacent waters and lowering the value of US naval dominance, and that a Chinese Eurasian order will erode US interest’. The 2017 US National Security Strategy implied that the BRI is a Chinese endeavour to displace the US in the region of Indo-Pacific, expand the spans of its state-driven economic model, and rearrange the area in its favour.

India is of the belief that the revival of such a humongous infrastructural project is basically a geo-strategic design to consolidate China’s naval/maritime strategy of access to the Indian Ocean in support of the PLA Navy’s future operations. It is also speculated that Beijing is engaged in a ‘colonial race’ in the Indian Ocean region, using ‘money’ and ‘power’ to secure resources for the Chinese economy and to secure naval base privileges in Myanmar (Burma), Sri Lanka, Seychelles, and Pakistan, which may turn out to be a strategic nightmare for India. Additionally, India is fretful, as China under the Belt and Road initiative, which is part of the ‘String of Pearls’ strategy for the Indian Ocean features the construction of a strategic port at Gwadar on the Arabian sea, will allow the Chinese to control ship traffic through Strait of Hormuz when the need arises.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies

Title image courtesy: https://www.beltroadresearch.com/