Small drones have emerged as critical assets in modern conflict zones worldwide. Their ability to penetrate constrained airspace, deliver real-time intelligence, and conduct precision strikes has fundamentally altered the tactical landscape. However, as drones proliferate, Electronic Warfare (EW) systems designed to intercept, jam, manipulate, or completely neutralise these platforms have expanded at an equivalent pace. The battlefield is now a contest not merely of platforms and payloads, but of electromagnetic dominance. The decisive question is whether small drones—specifically nano, micro, 7-inch, and 10-inch class systems—can maintain navigational integrity when GNSS denial, spoofing, and command-link interference become the standard operating environment.

This article provides a detailed assessment of how small drones can survive in an EW-saturated battlespace. It discusses multi-sensor navigation architectures, anti-spoofing technologies, autonomous fallback logic, swarm-based resilience, and cutting-edge research developments that are redefining survivability. The objective is to present a technically grounded evaluation suitable for defence planners,

The Electromagnetic Threat Environment

Modern EW systems focus on three principal areas of attack:

GNSS Denial (Jamming)

GNSS jammers emit high-power RF noise to saturate the L1, L2, and E1/E5 bands. Even portable jammers of 10–40 watts can create GNSS blackout zones several kilometres wide. For small drones dependent on satellite navigation for stabilisation, route following, and autonomous return-to-home, the effects are immediate: drift, loss of positional confidence, or failsafe descent. In Ukraine, FPV and commercial quadcopters routinely encounter GNSS loss within 5–10 km of front-line EW deployments.

GNSS Spoofing and Meaconing

Spoofing is a more sophisticated threat vector in which an adversary transmits counterfeit satellite signals with manipulated code phase, carrier phase, Doppler profiles, and navigation data. These falsified signals override legitimate GNSS broadcasts at the receiver front end, inducing the drone to compute an incorrect position, velocity, and time solution. The resulting navigation corruption manifests as unintended course deviations, premature mission termination, or controlled redirection into pre-planned engagement zones. Contemporary conflicts have demonstrated that both state and non-state actors now employ portable meaconing units, ground-based spoofers, and airborne EW platforms capable of generating deceptive satellite geometries tailored to mislead small UAS.

Command-and-Control (C2) Link Interference

Wideband electronic attack systems degrade UAV command-and-control links by saturating or denying the uplink/downlink channels used for telemetry, piloting inputs, and video transmission. For FPV-class drones, disruption of the C2 link is operationally more catastrophic than GNSS denial because loss of the real-time control channel results in immediate mission failure.

In asymmetric conflict environments, the drone’s own telemetry emissions can be exploited for emitter geolocation and operator triangulation, underscoring the need for robust, low-probability-of-intercept and low-probability-of-detection C2 architectures with adaptive power control, spectral spreading, and dynamic link management.

Solution: Multi-Layered Navigation Architecture

Survivability in such an environment demands a multi-layered navigation architecture that can withstand both broadband and narrowband jamming, including high-power noise flooding in the L1/L2/E1/E5 bands and targeted uplink suppression. This requires tightly coupled inertial–visual odometry as an independent state estimator, authenticated and multi-frequency GNSS to resist spoofed navigation messages, hardened C2 links utilising spread-spectrum and LPI/LPD waveforms, and autonomous integrity-management logic capable of isolating corrupted satellite solutions, rejecting falsified timing or Doppler inputs, and maintaining a stable navigation solution even under complete GNSS denial.

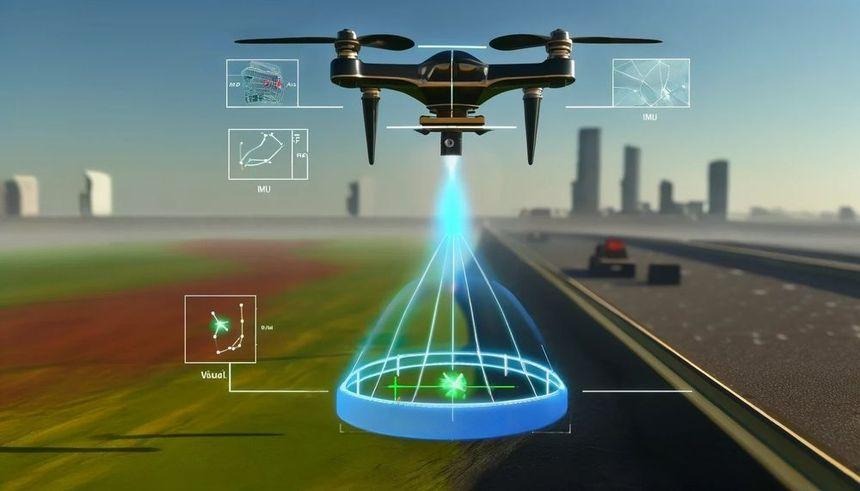

Multi-Sensor Navigation: The Foundation of EW Resilience

The most significant doctrinal shift in drone navigation philosophy is the transition from GNSS-centred navigation to GNSS-assisted, multi-sensor fusion.

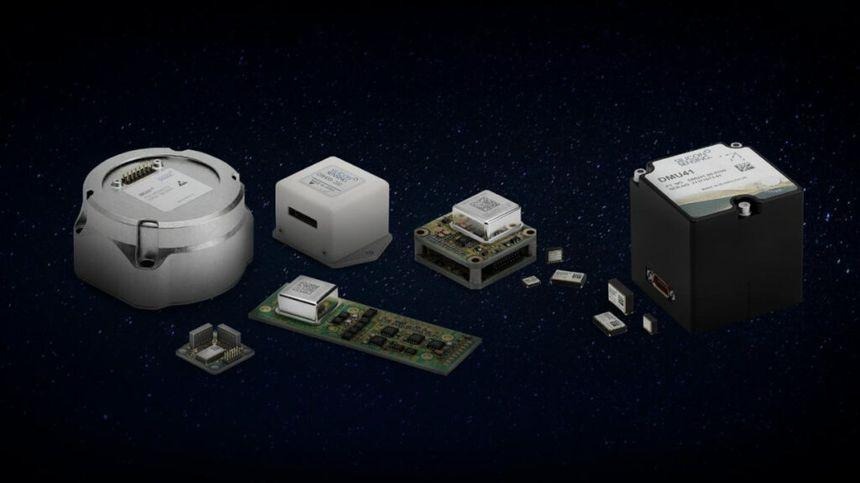

Inertial Navigation (INS)

Even small UAVs incorporate lightweight MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems)-based inertial sensors that measure acceleration and rotation to maintain short-term dead-reckoning when external signals are lost. Although these sensors accumulate positional drift over time, they provide sufficient stability to bridge short GNSS outages. With modern filtering and drift-correction techniques, small drones can typically sustain controlled flight for 20–60 seconds during complete GNSS loss, maintaining attitude, heading, and basic positional continuity until alternative navigation inputs become available.

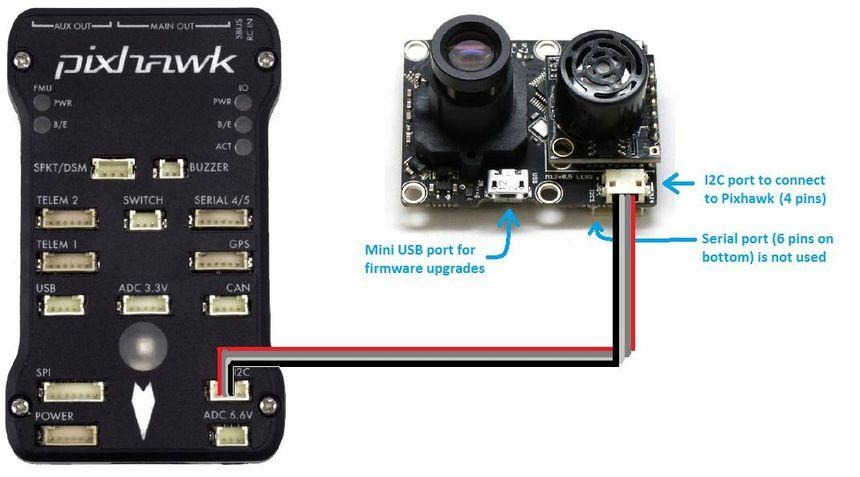

Visual-Inertial Odometry (VIO)

VIO is now a primary navigation method for small drones operating without GNSS. It works by tracking visual features across successive camera frames and combining this information with inertial measurements to estimate the drone’s movement. The camera provides a continuous stream of images that capture changes in the surrounding environment. At the same time, the inertial sensors measure short-term motion—such as acceleration and rotation—at high frequency. By aligning the visual changes with the inertial readings, the system generates a stable and accurate estimate of position and orientation. Because VIO depends entirely on onboard cameras and inertial units, it is unaffected by jamming or RF interference. Recent advancements have reduced its size and processing requirements enough for use on micro-UAVs, with field tests showing drift levels as low as 1–2% of the distance travelled

LiDAR-VIO Fusion

In visually degraded environments—such as dense vegetation, smoke-obscured areas, confined tunnels, or low-light conditions—LiDAR provides a reliable source of depth measurements that compensates for reduced camera visibility. Compact solid-state LiDAR units with 16–32 beams emit rapid pulses of light and measure the return time to build a precise 3D point cloud of the surrounding environment. When these depth measurements are fused with visual feature tracking and inertial sensor data, the drone gains a more accurate and stable estimate of its position, orientation, and motion. This LiDAR-VIO fusion reduces cumulative drift, enhances obstacle detection, and significantly improves terrain-following capability in environments where camera-only systems lose consistency.

Radar-Inertial Navigation

Millimetre-wave radar has become a significant advancement in small-drone navigation, offering reliable performance in conditions that degrade optical or LiDAR-based systems. Operating in high-frequency bands, these radars emit short pulses and analyse their reflections to determine distance, surface structure, and relative motion, enabling the drone to perceive its surroundings even in fog, dust, smoke, electromagnetic clutter, or near-total darkness. When radar measurements are fused with inertial sensor data, the system produces a stable odometry solution that remains reliable despite visual ambiguity. Several NATO programmes are now testing compact Millimetre-Wave radar–inertial modules under 150 grams, making them suitable for 10-inch class tactical drones that require resilient navigation in contested environments.

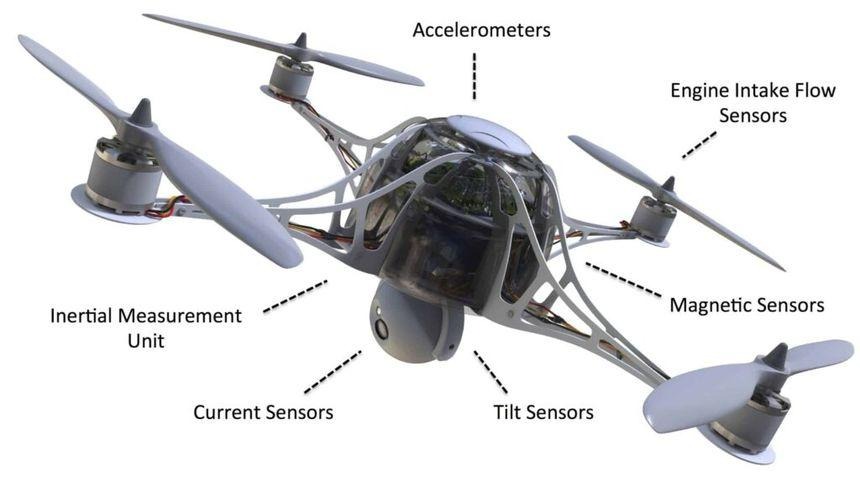

Supporting Sensors

Supporting sensors contribute additional layers of redundancy that strengthen the drone’s overall state estimation.

Optical-flow modules detect motion by analysing pixel shifts between successive downward-facing images, providing reliable velocity and position cues during low-altitude hover or GNSS-deny conditions.

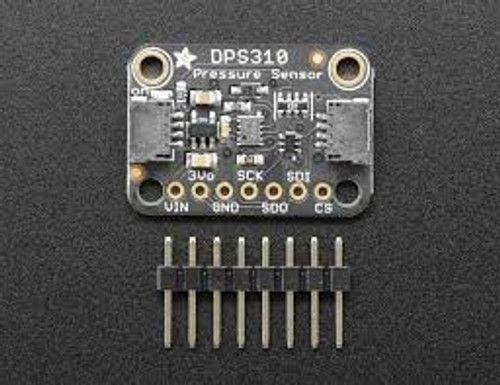

Barometric pressure sensors offer continuous altitude estimation by measuring small variations in ambient air pressure, enabling the drone to maintain vertical stability even when visual references are unavailable.

Magnetometers supply heading information by sensing the Earth’s magnetic field, though their accuracy can degrade in urban or metallic environments due to electromagnetic interference.

When integrated within the navigation filter, these secondary sensors provide complementary data streams that stabilise the attitude, altitude, and heading solution, ensuring the navigation system retains coherence when primary sensors degrade or fail.

Counter-Spoofing Architecture

Spoofing has emerged as the dominant navigation threat. Modern drones require layered defences that integrate multi-constellation GNSS authentication, inertial-visual odometry fusion, anomaly-detection algorithms, and autonomous mission-continuity behaviours to ensure that falsified satellite signals neither corrupt the navigation solution nor compromise operational outcomes.

Multi-Constellation, Multi-Frequency GNSS

Tracking GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou across multiple frequencies raises spoofing difficulty dramatically because the adversary must simultaneously replicate the distinct modulation schemes, carrier phases, Doppler histories, and time relationships of each constellation. Multi-band receivers cross-check these signals for consistency in power, geometry, and ionospheric delay, making any mismatch immediately detectable. When combined with authenticated services such as Galileo OSNMA, the attacker must also forge cryptographic signatures—a computationally infeasible task. As a result, even state-level actors struggle to generate a coherent, physically plausible, multi-frequency, multi-constellation spoofing environment.

Receiver-Level Anti-Spoofing

Modern GNSS receivers employ multiple layers of signal-integrity monitoring to detect and reject spoofed satellite signals before they are incorporated into the navigation filter.

Distortion-based checks analyse the correlation peak shape and code-phase symmetry to identify artificial or replayed signals.

Doppler shift validation compares the incoming carrier frequency against predicted satellite Doppler profiles, flagging signals whose frequency evolution is inconsistent with orbital mechanics.

Angle-of-arrival monitoring—using multi-antenna or spatial-processing techniques—detects spoofers by identifying signals arriving from a single ground-based source rather than from multiple satellites distributed across the sky.

In addition, receivers apply real-time anomaly scoring that evaluates signal strength patterns, inter-signal timing coherence, and cross-constellation consistency. Collectively, these receiver-level anti-spoofing measures enable the system to isolate falsified signals, prevent them from contaminating the navigation solution, and trigger autonomous fallback behaviours when spoofing attempts are detected.

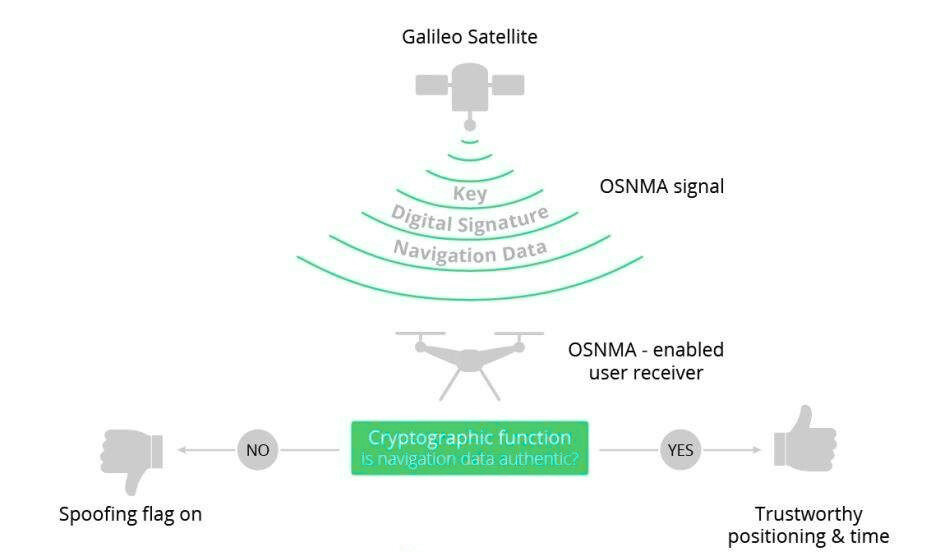

Cryptographic Authentication (Galileo OSNMA)

Galileo’s Open Service Navigation Message Authentication (OSNMA) provides a cryptographic layer that enables receivers to verify the authenticity of broadcast navigation messages and confirm that they originate from genuine Galileo satellites. OSNMA embeds Message Authentication Codes (MACs) within the navigation data and employs a TESLA-based delayed key-disclosure protocol, in which each MAC is generated using a secret key that is revealed only after its validity period has expired. This structure prevents attackers from forging future navigation messages, as the disclosed keys cannot be used to compute upcoming MACs or predict subsequent key values within the hash chain. Even if an adversary captures both the MAC and its corresponding key, the information is only valid for historical verification and cannot be repurposed for spoofing. As a result, counterfeit GNSS messages that replicate signal structure, power levels, or timing characteristics will still fail authentication at the data level.

OSNMA therefore introduces a robust, cryptographically anchored anti-spoofing capability previously unavailable to civilian drones, significantly enhancing resilience in contested electromagnetic environments

Inertial-Assisted Spoof Detection

Inertial-assisted spoof detection uses the drone’s inertial navigation system (INS) as an independent truth reference to validate incoming GNSS measurements.

The INS continuously estimates short-term position, velocity, and attitude based on accelerometer and gyroscope data sampled at high frequency. When the receiver obtains new GNSS updates, these measurements are compared against the INS-predicted state within predefined physical and kinematic limits. If a GNSS position, velocity, or timing update deviates from the INS forecast by more than what is physically achievable—such as sudden jumps in location, impossible acceleration profiles, or inconsistent heading changes—the data is classified as non-credible and excluded from the navigation filter.

This approach has long been employed in high-grade aviation and missile guidance systems and is now miniaturised for small UAS through lightweight MEMS IMUs and embedded filtering algorithms. By enforcing cross-checks between GNSS and inertial estimates, the system can immediately identify and reject spoofed satellite inputs, ensuring continuity of navigation even during sophisticated signal-manipulation attempts

Protecting C2 Links Against EW Attack

Navigation resilience collapses without dependable C2 links, as the command channel provides mission updates, operator inputs, telemetry feedback, and critical overrides. In EW-dense environments, wideband jammers and uplink suppression systems can corrupt or deny these signals, causing packet loss, latency, or complete link failure.

Small drones—especially FPV platforms—are highly sensitive to such disruptions because their control loops rely on continuous, low-latency guidance.

To remain operational, the C2 link must therefore employ spread-spectrum techniques, frequency hopping, adaptive power control, and low-probability-of-intercept waveforms that maintain link stability while reducing vulnerability to electronic attack.

Frequency-Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS)

By rapidly switching the transmission channel across a predefined set of frequencies, FHSS prevents a jammer from concentrating energy on any single uplink or downlink path long enough to deny it. The hopping sequence is synchronised between the drone and ground controller, allowing the link to re-establish itself even if individual hops are momentarily jammed. When combined with direct-sequence or other spread-spectrum modulation techniques, the signal energy is distributed over a wider bandwidth, lowering spectral density and making the waveform harder to detect, track, or overwhelm with noise. This dual-layer approach significantly reduces susceptibility to broadband and narrowband jamming, improves link robustness under high interference conditions, and complicates adversary attempts to perform uplink suppression or targeted RF interception.

Directional and Beam Forming Antennas

Small drones can now integrate lightweight directional and beamforming antennas that focus their radiated energy into a narrow lobe rather than broadcasting uniformly in all directions. This concentration of energy increases the effective link budget toward the intended ground station while simultaneously reducing the drone’s RF exposure to hostile jamming sources located outside the antenna’s main beam. Electronic or mechanically steered beamforming arrays further enable the antenna to dynamically adjust its pointing angle, maintaining optimal gain toward the controller even during manoeuvres, by suppressing sidelobes and minimising omnidirectional leakage. These antennas lower the probability of intercept and make it substantially harder for an adversary to inject interference or overpower the control channel. The result is a more resilient C2 link with improved resistance to both broadband and targeted jamming.

Multi-Path C2 Architecture

Modern drones should incorporate a multi-path command-and-control architecture capable of operating across several independent communication channels.

Primary RF link – The primary RF link provides the main low-latency path for flight control, telemetry, and real-time video, and is typically optimised for minimal latency and high link availability. This channel remains the principal means of operator input during dynamic missions and requires robust anti-jam measures to maintain continuity under electronic attack.

Mesh-based relay networks – Mesh-based relay networks add a second layer of resilience by allowing multiple drones or ground nodes to act as distributed communication points. This enables the platform to extend operational range, overcome line-of-sight constraints, and dynamically route around localised jamming or terrain-based signal blockages. Mesh routing algorithms continuously evaluate node availability and interference levels, selecting the most reliable path to maintain link integrity

Opportunistic LTE/5G – Opportunistic LTE/5G connectivity serves as an auxiliary high-bandwidth option when tactical or civilian cellular infrastructure is present. These links provide strong throughput for telemetry and video transmission, automatic handover between towers, and inherent resistance to narrowband jamming due to their spread-spectrum and multi-carrier nature. However, availability depends on local network presence and security considerations.

Satellite narrowband links for advanced platforms – For advanced platforms requiring beyond-line-of-sight capability, narrowband satellite links provide a strategic fallback channel. These links maintain functionality even when terrestrial RF paths are compromised by jamming, terrain masking, or infrastructure loss. Low-bitrate satellite modems allow for reliable command updates and emergency overrides, ensuring mission continuity at extended ranges.

Intelligent link-management software coordinates all communication paths by monitoring signal strength, interference levels, latency, and packet-error rates in real time. Based on these metrics, the system performs autonomous switching between RF, mesh, LTE/5G, and satellite channels without interrupting the control loop. This multi-layered C2 architecture substantially enhances survivability and maintains operational coherence in contested electromagnetic environments.

Low-Probability-of-Intercept (LPI) Techniques

Burst telemetry reduces intercept risk by transmitting command and status data in short, high-rate packets instead of continuous streams. In contested environments where adversaries employ wideband receivers to scan for drone emissions, this intermittent transmission profile sharply limits the exposure window and makes the signal far harder to isolate or track.

Spectral spreading disperses the signal energy across a wider bandwidth using techniques such as direct-sequence or frequency-hopping spread spectrum. Against modern EW systems that rely on detecting narrowband spikes or characteristic modulation patterns, a spread-spectrum waveform blends closer to the noise floor, making classification, interception, and targeted jamming significantly more difficult.

Low-duty-cycle communication further reduces detectability by keeping the transmitter active only for brief, strategically timed intervals. In operational settings, this minimises the drone’s RF footprint and complicates adversary attempts to perform Time Difference of Arrival (TDOA) or Angle of Arrival (AoA) geolocation of the operator, a tactic increasingly used in asymmetric conflicts to target launch teams.

Autonomy and Fail-Operational Behaviour

Effective EW resilience requires drones to incorporate autonomous and fail-operational behaviours that preserve mission continuity when external navigation or control inputs are disrupted. In high-interference environments—where GNSS may be spoofed, denied, or corrupted, and C2 links may experience latency, packet loss, or full suppression—the platform must rely on onboard integrity checks, internal sensor fusion, and predefined fallback logic to maintain stable flight. These autonomous functions enable the drone to identify unreliable measurements, reconfigure its navigation solution, and continue executing mission-critical tasks even in the absence of real-time operator guidance.

GNSS-Deny Autonomous Behaviours

When GNSS integrity degrades or becomes unreliable, the drone must transition immediately to inertial–visual navigation using INS and VIO as the primary state estimators. In this mode, inertial sensors provide high-rate attitude and motion data while visual odometry supplies positional updates derived from environmental features. Together, they maintain a coherent navigation solution independent of external signals.

Predefined ‘EW-safe’ corridors enable the drone to follow mission-planned routes that avoid known jamming zones, spoofing emitters, or terrain that historically degrades GNSS performance. These corridors rely on internal waypoints and geometric constraints stored onboard, allowing the Drone to maintain safe routing even when real-time GNSS updates are unavailable.

Heading stability is maintained through inertial cues derived from gyroscopes and accelerometers, with magnetometer inputs incorporated where interference levels permit. By relying on inertial heading rather than GNSS track, the drone can preserve correct orientation and flight direction during prolonged GNSS outages or during attempts by an adversary to manipulate satellite-based course information.

Mission logic continues through internal state estimation, enabling the drone to execute preassigned tasks—such as reaching target coordinates, holding altitude, or completing terminal manoeuvres—without external navigation or operator input. This autonomous behaviour ensures that essential mission objectives can still be achieved even under sustained EW pressure.

Anti-Spoofing Behaviors

When spoofing is detected through signal-integrity monitoring or inconsistencies between GNSS and inertial–visual estimates, the drone must immediately disregard all satellite-based position, velocity, and timing data. This prevents falsified GNSS measurements from contaminating the navigation filter or influencing flight-control logic.

Navigation must then transition fully to inertial–visual fusion, using high-rate inertial measurements as the primary motion source and visual odometry or LiDAR/VIO inputs to correct drift. This internally referenced state-estimation framework ensures stable navigation performance even in the complete absence of trusted GNSS signals.

All return-to-home (RTH), geofencing, or waypoint routines that depend on GNSS must be disabled or reconfigured, as spoofed satellite inputs can misdirect the drone toward hostile zones or cause premature mission aborts. Instead, RTH and safety behaviours must rely on inertial position propagation or mission-defined fallback vectors.

The drone must maintain its mission trajectory using internal estimation and preprogrammed logic, allowing it to continue toward target coordinates, preserve formation geometry, or execute terminal manoeuvres without external navigation support. This autonomy ensures mission continuity even under sustained, high-grade spoofing attempts.

Swarm-Level Autonomy

In swarm-level autonomy, each drone continuously exchanges state information—such as position, velocity, heading, and sensor confidence metrics—with other members of the formation. This creates a distributed situational-awareness network that allows the swarm to maintain a collective understanding of its geometry and movement independent of external navigation aids.

When spoofing or GNSS degradation affects a single drone, its navigation estimates begin to diverge from the consensus formed by the remaining units. Swarm consensus algorithms—such as weighted averaging, fault-tolerant filtering, or distributed Kalman fusion—identify these anomalies by comparing each drone’s reported state against the predicted formation model and the internally validated estimates of neighbouring units.

Once a drone is identified as providing inconsistent or non-credible data, the swarm isolates it by reducing its influence in the decision-making graph or excluding it from position-sharing loops altogether. This prevents corrupted navigation data from propagating through the formation or degrading the swarm’s collective state estimation.

By leveraging cross-validation, redundancy, and distributed integrity checks, swarm drones maintain coherent formation control and navigational stability even in dense EW environments where individual units may experience spoofing, jamming, or sensor degradation. This distributed autonomy significantly enhances resilience and mission reliability under hostile electromagnetic conditions.

Global Research and Development Trends

High-Speed VIO for Tactical Drones

High-speed VIO has become a central focus of global R&D as militaries seek navigation solutions capable of supporting fast, agile manoeuvres in GNSS-denied environments. Recent advances have produced low-latency visual–inertial pipelines operating below 30 milliseconds, enabling stable state estimation for FPV-class and high-agility tactical drones that experience rapid accelerations, high angular rates, and frequent vector changes. These systems optimise feature extraction and inertial integration to remain reliable under motion blur, low-texture conditions, and aggressive manoeuvring, while ongoing defence programmes are developing hardware accelerators and FPGA-based processors to deliver this performance within strict SWaP limits. As a result, high-speed VIO is emerging as a core navigation layer for tactical drones requiring resilient guidance and control under electronic attack.

LiDAR-VIO and Radar-VIO Fusion

LiDAR–VIO fusion is receiving significant global R&D investment as forces seek navigation systems that remain stable when visual features degrade. Modern solid-state LiDAR units generate dense 3D point clouds even in smoke, dust, foliage, or low-light conditions, providing depth measurements that correct visual drift and strengthen terrain-relative navigation. Current research focuses on tightly coupled LiDAR–inertial–visual pipelines that integrate depth returns directly into the state estimator, reducing positional drift by 40–70% in GPS-denied trials. Defence laboratories in the US, Europe, Israel, and South Korea are fielding ultra-light LiDAR modules and optimised fusion algorithms designed to meet the SWaP limits of 7–10-inch tactical drones operating in cluttered or EW-contested environments.

Radar–Inertial Odometry

Radar–inertial odometry has emerged as a major R&D priority due to its ability to operate in conditions that defeat both cameras and LiDAR. Millimetre-wave radar provides robust range and velocity measurements through fog, rain, dust, smoke, and electromagnetic clutter, supplying stable environmental cues even when optical sensors degrade. Current research integrates radar returns directly with inertial sensors using tightly coupled filters that produce consistent odometry during high-speed flight or low-visibility operations. NATO programmes, particularly in the UK, France, and Germany, are developing compact Millimetre-wave modules under 150 g with high refresh rates, enabling 10-inch tactical drones to maintain reliable navigation in environments where traditional sensor suites fail.

GNSS Authentication and OSNMA Integration

GNSS authentication is a rapidly advancing field, with Galileo OSNMA leading global adoption for civilian and dual-use platforms. OSNMA embeds cryptographic Message Authentication Codes within the navigation message stream and uses delayed key disclosure to prevent adversaries from forging future satellite messages. Ongoing R&D focuses on accelerating verification routines, reducing computational overhead for small UAV processors, and integrating OSNMA with multi-constellation, multi-frequency receivers to enable stronger cross-checking against spoofed signals. Several major OEMs and defence agencies are now testing OSNMA-enabled chipsets for tactical drones, marking a major step forward in securing satellite-based navigation in contested electromagnetic environments.

AI-Driven Integrity Monitoring

AI-driven integrity monitoring is becoming a core component of next-generation drone navigation systems. Using machine-learning models trained on GNSS, inertial, and visual signal patterns, these systems can detect spoofing, jamming, sensor faults, or abnormal dynamics far earlier than traditional threshold-based filters. Current research focuses on neural filters that estimate measurement credibility, classify spoofing signatures, and adaptively reweight or exclude corrupted inputs within the navigation solution. Defence organisations in the US, Japan, and the EU are developing lightweight inference engines optimised for embedded processors, enabling small drones to autonomously identify and isolate compromised sensors in real time and maintain stable navigation in heavy EW conditions.

Emerging Resilient Navigation Systems

Defence R&D programmes are experimenting with:

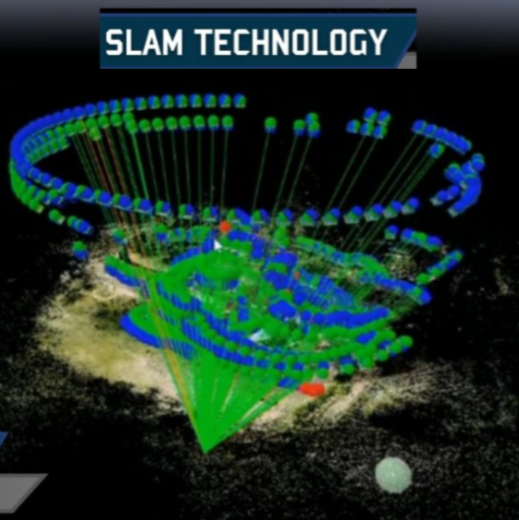

Vision-based SLAM optimised for micro-UAVs: Recent R&D adapts simultaneous localisation and mapping (SLAM) algorithms to the severe Size, Weight, and Power (SWaP) constraints of micro-UAVs. These implementations prioritise sparse, feature-based mapping, incremental pose-graph updates, and lightweight loop-closure detection to bound drift while minimising compute. Key engineering advances include hardware-accelerated feature extraction, asynchronous keyframe selection to reduce bandwidth, and tightly coupled visual–inertial factor graphs that push correction into the estimator rather than into heavy post-processing. The result is a compact SLAM pipeline capable of producing consistent local maps and sub-meter relative pose accuracy in GNSS-denied urban corridors, indoors, and in repetitive-terrain conditions where traditional VIO drifts accumulate.

Passive RF navigation (signal-of-opportunity tracking): Passive RF navigation exploits ambient transmissions — commercial cellular beacons, Wi-Fi access points, broadcast TV/FM, and other opportunistic emitters — as external references when GNSS is unavailable. Modern implementations use time-difference-of-arrival (TDOA), received-signal-strength (RSS) fingerprinting, and cross-correlation of known broadcast signatures to estimate bearing and range relative to multiple emitters. Integration with the onboard INS is performed via a probabilistic filter that treats signal-of-opportunity fixes as intermittent pseudo-observations with context-dependent covariances. The method is low-power, covert (receive-only), and particularly valuable in urban and littoral environments where RF infrastructure is dense; its limitations centre on emitter database freshness, temporal variability, and multipath, which modern filters mitigate via robust weighting and environment-aware modelling.

Magnetic-anomaly mapping for subterranean and denied environments: Magnetic-anomaly navigation leverages local variations in the Earth’s magnetic field as a persistent environmental fingerprint for localisation when GNSS and optical sensors fail (e.g., subterranean tunnels, dense foliage, or GPS-denied indoor complexes). High-sensitivity magnetometers collect vector magnetic samples that are matched to pre-surveyed magnetic anomaly maps or used to build on-the-fly magnetic maps via SLAM-like back-end optimisation. Practically, this requires careful compensation for platform magnetic bias, ferrous payload interference, and temporal field fluctuations; recent work combines magnetic observables with odometry priors in a tightly coupled filter to provide bounded lateral localisation errors. While not a universal solution, magnetic-anomaly techniques provide an additional independent navigation cue in environments where other modalities are compromised.

Conclusion

Drones will remain decisive assets in tactical and operational battlespaces only if their navigation and control systems are purpose-built to function within dense and persistent electronic-warfare environments. Reliance on GNSS as the primary navigation source is no longer sustainable; modern conflicts have demonstrated that jamming, spoofing, and uplink suppression can be applied at scale, with precision, and at progressively lower cost. Survivability now depends on a layered navigation architecture that integrates inertial–visual fusion, LiDAR and radar-based odometry, authenticated multi-constellation GNSS, and robust receiver-level spoof detection. Equally critical are hardened C2 channels leveraging spread-spectrum techniques, frequency agility, beamforming antennas, and low-probability-of-intercept waveforms to ensure continuous operator authority under electronic attack.

Autonomy and fail-operational logic must allow the drone to isolate corrupted sensors, reconfigure its navigation filter, and sustain mission execution when external signals collapse. AI-driven integrity monitoring, swarm-level consensus behaviours, and emerging resilient modalities such as passive RF navigation and magnetic anomaly mapping are rapidly becoming integral to next-generation platforms. Collectively, these technologies shift the drone from a signal-dependent asset to a self-reliant system capable of maintaining positional integrity, flight stability, and mission relevance in the face of deliberate interference.

For forces operating in high-threat theatres, adopting these measures is essential to preserving the tactical utility of small drones. Only those platforms engineered with multi-sensor resilience, cryptographic protection, autonomous recovery behaviours, and hardened communication links will remain effective inside contested electromagnetic zones, where the spectrum itself has become a primary domain of warfare.

Title Image Courtesy: Google Gemini AI

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and the Defence Research and Studies

References

GNSS, Spoofing, and Authentication

Humphreys, T. E. “GNSS Spoofing and Detection.” Proceedings of the IEEE, 104(6), 2016. Psiaki, M. L., & Humphreys, T. E. “GNSS Spoofing: Techniques and Countermeasures.” IEEE Spectrum, 2016. European Union Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA). Galileo OSNMA – Service Definition and ICD, 2021–2023. Jafarnia-Jahromi, A., et al. “Power Monitoring for GNSS Spoofing Detection.” GPS Solutions, 2012. Akos, D. “Signal Quality Monitoring for GNSS Spoofing Detection.” ION ITM, 2012.

Inertial Navigation, Sensor Fusion, and Spoof Rejection

Titterton, D. H., & Weston, J. N. Strapdown Inertial Navigation Technology. IET Press, 2004.

Grewal, M. S., & Andrews, A. P. Kalman Filtering – Theory and Practice. Wiley, 2015.

Farrell, J. A. Aided Navigation: GPS with High-Rate Sensors. McGraw-Hill, 2008.

Visual-Inertial Odometry (VIO) & SLAM

Leutenegger, S., Lynen, S., et al. “Visual–Inertial Odometry Using Nonlinear Optimization.” International Journal of Robotics Research, 2015.

Mur-Artal, R., & Tardós, J. D. “ORB-SLAM2: A Versatile SLAM System.” IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 2017.

Qin, T., et al. “VINS-Mono: A Robust Monocular Visual–Inertial Estimator.” IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 2018.

LiDAR and LiDAR–VIO Fusion

Zhang, J., & Singh, S. “LOAM: Lidar Odometry and Mapping in Real Time.” RSS, 2014.

Shan, T., & Englot, B. “LeGO-LOAM: Lightweight LiDAR Odometry.” IROS, 2018.

Fan, L., et al. “Tightly Coupled LiDAR–Visual–Inertial Fusion.” IEEE Sensors Journal, 2021.

Radar Odometry and mmWave Navigation

Kellner, F., et al. “Millimetre-Wave Radar Odometry for Robotics.” IEEE RA-L, 2022.

Wang, Y., et al. “Radar-Inertial Navigation for Autonomous Vehicles.” IROS, 2020.

Texas Instruments. mmWave Radar for Robotics – Technical Notes, 2019–2023.

Electronic Warfare, Jamming, and C2 Protection

Adamy, D. EW 101: A First Course in Electronic Warfare. Artech House, 2001.

Schleher, D. C. Electronic Warfare in the Information Age. Artech House, 1999.

NATO STO TR-SET-260. Counter-UAS RF Challenges, 2021.

Swarm Autonomy and Distributed Navigation

Olfati-Saber, R., & Murray, R. “Consensus Protocols in Multi-Agent Systems.” IEEE TAC, 2004.

Michael, N., et al. “Cooperative Control of UAV Swarms.” IEEE Control Systems Magazine, 2011.

Yang, G., et al. “Distributed State Estimation for UAV Networks.” IEEE TAES, 2019.

Signals of Opportunity (Passive RF Navigation)

Abdel-Hafez, M., et al. “Signals-of-Opportunity Navigation.” IEEE Aerospace Conference, 2016.

Lo, S., & Enge, P. “Resilient PNT Using Terrestrial Signals.” ION GNSS+, 2015.

Magnetic-Anomaly Navigation

Sheinker, A., et al. “Magnetic-Anomaly Navigation.” IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, 2013.

Lenz, E. “Magnetic-Field Navigation in GPS-Denied Environments.” IEEE Sensors, 2020.

AI-based Integrity Monitoring & Spoof Detection

O’Driscoll, C., & Wisniewski, A. “Machine Learning for GNSS Integrity Monitoring.” ION GNSS+, 2020.

Zhang, X., et al. “Deep Learning-Based GNSS Spoofing Detection.” GPS Solutions, 2021.

Zeng, Q., et al. “AI-Enhanced Sensor Fusion for UAV Navigation.” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2022.