Israel’s decision to recognise the Somaliland region in northwestern Somalia took the world by surprise. Apart from the Somaliland sovereignty, Somalia has some major issues like climate crises, armed conflicts, mass displacement, extreme poverty, widespread malnutrition, environmental degradation, human rights abuses and resurgence of sea piracy in the Gulf of Eden.

Abstract

This paper examines the reason behind the sudden resurgence of piracy after 2022, which has become a major concern for the international community due to the strategic importance of the Gulf of Aden in global trade. It tries to explore the efforts made to build the state of Somalia over the past decade, since its decline from peak levels. The research moves beyond deterrence-only explanations usually given and instead examines additional factors such as governance, institutional reforms, community perceptions, and pirate adaptations. With this, it aims to assess whether the decline in piracy is sustainable or not, and to offer possible explanations for the resurgence. Using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods of research, the study finds that the decline is not lasting. The analysis reveals that, although progress has been made in state-building, significant issues persist—including persistent grievances among communities and pirate networks that have not been dismantled—which could lead to piracy resurfacing on the global stage if deterrence fails. These findings suggest the need to focus on state-building efforts primarily to ensure the decline lasts. The study also offers some policy recommendations at the end to help mitigate the identified challenges to some extent.

Introduction

In March 2024, the Indian Navy captured 35 Somali pirates in the Arabian Sea, freeing a hijacked carrier and its crew. The operation, the largest apprehension of Somali pirates in the last decade, reignited questions about Somali piracy that many had thought to be resolved. For much of the past decade, declining attack numbers created the impression that piracy had come to an end. And yet the 2023-2024 rise in attacks suggests that silence may not necessarily mean “the end.”

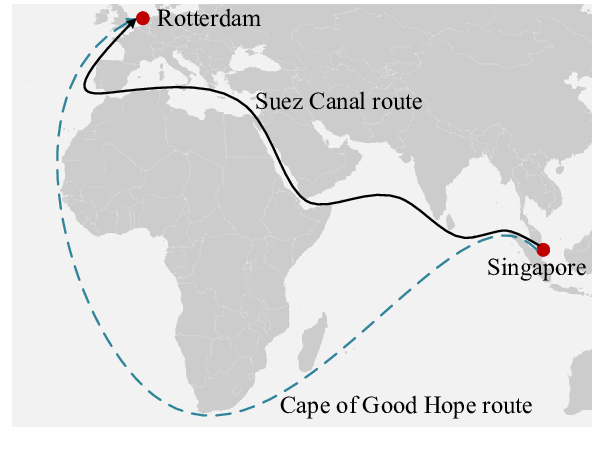

The Gulf of Aden, one of the busiest maritime corridors, links the Indian Ocean with the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean, “a shortcut” if compared to the Cape of Good Hope route. This shortcut accounts for approximately 22 per cent of global container trade and handles significant volumes of oil, LNG, LPG, and bulk commodities (UNCTAD, 2024a). Disruption here forces vessels to take a roundabout route around the Cape of Good Hope, adding an extra 42 per cent to voyage distances on Asia-Europe routes, thereby inflating prices.

The late-2023 Red Sea crisis once again reminded the international community of its strategic importance, where attacks on shipping caused an 82 per cent fall in container tonnage through the Suez Canal, as well as a 70 per cent drop in ship entries into the Gulf of Aden between December 2023 and February 2024 (UNCTAD, 2024b). All while the Cape of Good Hope traffic increased by 60 per cent. This is clearly illustrated in Figure 1, where the crisis immediately impacted global shipping flows, resulting in increased freight and fuel rates worldwide. This is exactly why, given Somalia’s strategic location at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden, piracy originating from its coast can never be a purely local concern; its persistence or resurgence will be of international importance.

Figure 1: Traffic maps comparing the shift in container ship routes from the Suez Canal to the Cape of Good Hope

Source. From Navigating Troubled Waters Impact to Global Trade of Disruption of Shipping Routes in the Red Sea, UNCTAD, 2024, p. 4 (https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/osginf2024d2_en.pdf).

However, Somali piracy dates back centuries and has roots in the cultural practices of Somali coastal communities, where opportunistic maritime raiding has long existed in their waters (Ingiriis, 2013). Yet, before the 1990s, pirate activities were not widespread. Although centuries of colonialism left the economy fragile, the coastal towns, as described in Table 1, had organised economies through fishing cooperatives, salt production, and port-based commerce. The state regulated the coastal economy via the Somali Navy, Ministry of Maritime Transport, and Fisheries Law No. 13 (1985), which oversaw, licensed, and regulated access to maritime resources (UNEP, 1987). According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, FAO, in the late 1980s, thousands of small-scale fishing boats (artisanal fleet) employed about 90,000 people, including fishermen and those involved in related activities (FAO, 2005a). Fishing cooperatives supported these fishermen by providing equipment and cold storage facilities. But things changed after the fall of Siad Barre’s authoritarian regime in 1991.

Somalia, after gaining independence from the British and Italian colonial powers, unified and established itself as a democracy in 1960. Despite this unification, regional divides persisted and deepened as democratic governance became centred around Mogadishu’s elite (Davies et al., 2023a). In 1969, Somalia’s democracy ended when General Siyad Barre’s coup d’état succeeded. During his rule, Somalia took a fully totalitarian path, further entrenching regional divides until rebel groups ousted him. In this power vacuum, the lack of a strong central authority led rogue actors to turn against each other in a bid to compete for control over Mogadishu and ultimately Somalia; clan elders, militias, and elites fought among themselves. Suddenly, with Somalia’s fall, its state institutions, including those guarding the 3,330 km coastline, also ceased to operate. The absence of regulation opened Somali waters to foreign industrial vessels engaged in illegal, unregulated, unreported (IUU) fishing along the coast. These fleets encroached into inshore zones, destroyed artisanal gear, and even caused fatal confrontations with locals, while depleting fish stocks such as sharks, tuna, and lobsters (FAO, 2005b). Eventually, Somali artisanal fishing income began to collapse, unable to withstand the unfair competition. Grievances deepened when allegations of toxic dumping emerged. This is where it all started. The attacks initiated as small, sporadic confrontations by coastal fishers demanding fines from illegal trawlers. But, over time, these raids became a substitute for the absence of legitimate livelihoods.

However, piracy did not develop uniformly along the entire 3,330 km coast of Somalia. Somaliland, on the northwest coast, declared independence immediately after the 1991 collapse and began building its own state institutions. The rest of the country was divided among factions; the South (Mogadishu) was a battleground for the rebel groups. It was not until 1998 that Puntland, on the northeast coast, declared itself a semi-autonomous, self-governing state, although governance there has remained under-resourced and selective. As Table 1 shows, piracy is clustered in coastal towns such as Eyl, Bandarbeyla, and Bargal, primarily in Puntland, where artisanal fishing has been extreme (Hansen, 2009a). IUU has most affected this region. With weak governance and proximity to key shipping lanes, most coastal towns in Puntland naturally became hubs for piracy. Bossaso, unlike others, had relatively stronger government oversight due to its commercial importance, which relatively hindered the spread of piracy. Similarly, Somaliland maintained deterrence through strong governance, functioning Sharia courts, coast guards, and the opposition of clan elders (Hansen, 2009b). Meanwhile, the conflict-ridden and diverse economy of southern Somalia, along with negative social perceptions of piracy, limited the spread there.

Somaliland and Puntland had more stable governments, where governance was institutionalised. In contrast, much of Central and Southern Somalia’s state functions relied on informal systems rooted in clan or religious affiliations. Still, clans remained fragmented here, resulting in fragile governance (Davies et al., 2023b). In parts of central Somalia, as Table 1 indicates, entrepreneurial organisers from Puntland institutionalised piracy despite weaker fishing traditions (Hansen, 2009c). Limited livelihood options, lack of governance, and the strategic location of the central coastal towns near crucial sea lanes and deep anchorages made them a haven for this newfound business.

Table 1: Regional Variation in Piracy Emergence Along the Somali Coast

| Region | Coastal Towns | Pre-1991 Economy | Post-1991 Economy | Piracy Status | Reason |

| Somaliland (North-West) | Zeila; Berbera; Las Korey | Berber: major livestock-export port; artisanal fishing supplementary; salt production | Fishing remained secondary; cooperatives collapsed; some private rehabilitation | Not a single piracy hub | Strong artisanal fishing, port trade, and salt production |

| Puntland (North-East) | Bossano; Barga; Ras Hafun; Bandarbeyla; Eyl, etc. | Fisheries are minimal; ports under militia control; few livelihood alternatives | Still the strongest artisanal zone | Piracy hotspot (Except Bossano) | Weak & selective local governance; grievances due to IUU are higher here |

| Central Somalia | Garad; Hobyo; Harardheere | Weak fishing sector; livelihoods centred on pastoralism, charcoal and salt; limited port activity | Fisheries minimal; ports are under militia control; few livelihood alternatives | Few but major piracy hubs at Hobyo and Harardheere | Absence of governance. No maritime regulation; presence of entrepreneurial pirate organisers from Puntland |

| Southern Somalia | Mogadishu; Merca; Brava; Kismayo; Kulmis; Raskiamboni | Mixed livelihoods: artisanal fishing, delta agriculture, pastoralism; ports exported livestock, hides, fish, salt; tanneries and processing plants | Cooperatives collapsed; industrial gear destroyed; ports militarised; trade fragmented | Limited. Occasional staging in Kismayo; no sustained piracy in Mogadishu, Brava or Raskiamboni | Conflict-dominated, some stability needed for piracy to organise; diversified economy; piracy is disruptive to existing businesses; socially dishonourable |

Source. Compiled by the author from FAO (2005)[1], UNEP (1987)[2], and Hansen (2009)[3].

By the early 2000s, fishing cooperatives and infrastructure had already disintegrated, effectively destroying fishing as a livelihood (FAO, 2005c). And, over time, piracy became increasingly organised and professionalised. What initially emerged as a form of resistance to IUU fishing turned into a means of solving economic desperation.

By the mid-2000s, pirate groups operated with mother ships, GPS, and satellite phones, extending their reach deep into the Indian Ocean and transforming maritime predation into a significant revenue stream for militias and warlords. In some towns, such as Eyl, Hobyo, and Harardheere, piracy revenues became the primary economic driver, funding local construction projects and even marriage payments (Hansen, 2009d). From 2007 to 2011, during peak years, piracy reached new levels, capable of hijacking super-tankers thousands of miles offshore.

Eventually, this became a nuisance to the global shipping industry, forcing the international community to intervene. The following years saw a series of coordinated maritime interventions, from international naval deployments to the adoption of BM5 measures by commercial ships (Hodgkinson, 2013). The result? Piracy off the coast of Somalia decreased. But around this time, it was realised that fully resolving piracy required stabilising Somalia and addressing its underlying causes. State-building efforts were launched, exemplified by the establishment of the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) in 2012.

However, as previously discussed, piracy resurged in 2023 after a decade of decline. Interestingly, this occurred immediately after the international naval patrols lost their authority to operate specifically within the Somalian territorial waters following the expiration of the UN mandate in 2022 that authorised such operations (UNSC, 2022a). This event poses a key question: for piracy to re-emerge just after the weakening of naval deterrence, was the decline that was maintained from 2012/2013 truly a sustainable one? Did piracy really eradicate? The state-building efforts undertaken, such as institutional building, governance, and livelihood interventions in the past decade, were they not successful enough?

To explore this systematically, the study is guided by the following research questions:

- Is the decline after 2012/2013 a durable outcome?

- How have institutional and governance reforms contributed to maintaining this decline?

- To what extent have coastal livelihoods and community perceptions supported or undermined it?

- What happened to pirate organisations during the decline?

By addressing these questions, the study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of state-building efforts over the past decade and determine whether the apparent decline in piracy represents a genuinely durable transformation.

Methodology

The study’s methodology is based on a combination of qualitative and quantitative research. This approach utilised a combination of primary and secondary sources, with minimal supplementary consultation of tertiary sources to source data.

Literature Review

Many scholars have pinpointed piracy’s emergence to state anarchy, youth unemployment, and the lack of institutions, which created a conducive environment for illegal activities (Karawita, 2019a; Djama, 2011a). With this as context, the exploitation of Somalia’s maritime resources through IUU fishing and toxic waste dumping has worsened local grievances, leading coastal communities to see piracy both as a way to survive and as a form of resistance. Supporting this, Bueger (2013) also argues that Somali piracy was not sustained solely due to economic hardship and weak governance; he says that social approval too played a role, which portrayed pirates as defenders of Somali sovereignty against foreign exploitation, indicating that piracy’s persistence cannot be explained just by economic factors alone.

The sharp rise in piracy attacks during the 2000s prompted unprecedented international naval intervention in the Gulf of Aden. Møller (2009) notes that the Somalian coast turned into a hub of global cooperation, with NATO, EU, and U.S.-led coalitions operating alongside Chinese, Russian, and Indian naval forces. He argues that this convergence resulted from framing piracy not just as a maritime crime but instead as a security threat, which authorised significant resource commitments. Regional initiatives, especially the Djibouti Code of Conduct, aimed to provide regional responses were also launched, although their effectiveness was limited because long-term solutions were needed to empower Somali and local governance actors (Madsen & Kane-Hartnett, 2014).

Hodgkinson (2014) highlights a uniqueness in Somalia’s case; he states that while suppression measures worked in the Horn of Africa, replicating the same approach in the West Coast of Africa and Southeast Asia would be challenging, mainly because those regions lack the same international will that contributed to success, revealing the asymmetry in global concern.

Earlier scholars, such as Berube & Murphy (2008), believed that piracy could only be defeated by addressing land-based causes. Later, Karawita (2019b) supported this view, emphasising that maritime interventions alone are insufficient without parallel efforts to rebuild Somalia’s institutional capacity and economic resilience. However, Jakobsen and Henningsen (2024) argue otherwise, claiming that the decline after 2013 happened without state-building efforts. Instead, they contend that strong leadership from major powers, combined with broad support from local, regional, and international actors both diplomatically and militarily, along with capable military forces and restrained use of force, has produced results. These conditions, implemented through international naval coordination, industry self-protection measures, and regional capacity-building, were enough to “end” piracy despite the lack of significant onshore rehabilitation. This view challenges the development-centred approach to solving piracy. Their deterrence-only explanation downplays the roles of governance and livelihoods in aiding the decline.

Many scholars also point out that legal responses, too, have lagged. UNCLOS provides the jurisdictional basis for prosecuting piracy, but its narrow provisions, which are limited to “acts committed for private ends” on the high seas, have left gaps (Karawita, 2019c). Djama (2011b) specifically argues about the prosecutorial gaps it has left, especially in the cases of politically motivated hybrid instances of maritime violence. In contrast, Elagab (2010) argues against merging piracy and terrorism into a single framework, arguing that terrorism already has extensive regulation, and conflating the two could just cause confusion. Djama (2011) also notes that many states, wary of costs and human rights issues, opted for release rather than trial for offenders. Regional prosecutions in Kenya, Seychelles, and Mauritius, supported by EU NAVFOR’s Operation Atalanta, helped fill this gap (Djama, 2011c; Karawita, 2019d).

Overall, after reviewing extensive scholarship, it is clear that the international community focused disproportionately on piracy, especially in the Gulf of Aden—emphasising naval deterrence and industry self-protection measures—which are credited as key factors in reducing piracy. However, a significant gap remains, as the scholarship lacks a detailed discussion of the role of state-building efforts that were attempted in rehabilitating and addressing Somalia’s grievances. Most accounts either cover deterrence or just emphasise the need for state-building efforts, with very little attention given to the specific efforts undertaken in Somalia and their contribution to ending piracy.

This gap, therefore, reinforces the research problem introduced earlier; since piracy declined from its peak years, several state-building efforts have been made in Somalia. After a decade of decline, what is the status of those efforts? Have they addressed Somalia’s underlying problems? If these issues remain unaddressed, the decline could reverse if deterrence weakens, making it unsustainable. And this would explain the resurgence in Piracy. That is why this paper will explore in more depth the state-building efforts and their effects on governance, institutional development, livelihoods, community perceptions, and pirate adaptations, moving away from the deterrence-only explanation, aiming to comprehensively understand if the decline in piracy is truly sustainable or not.

Governance and Institutional Reforms

Following the collapse of the state in 1991 and the subsequent years of chaos, Somalia needed policies to rehabilitate its population. Implementing such policies required effective institutions and a functioning government; thus, the first step was to establish a unified national authority.

However, given the country’s regional divisiveness under the Mogadishu-centred democracy and Barre’s authoritarian regime, a centralised system of governance was no longer considered effective. And, to overcome this, Federalism was therefore regarded as a solution. Although the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia (TFG), with its federal structure, was formally established in 2004, it struggled to exercise any real administrative power. Federalism in Somalia only became operational here with the adoption of the Provisional Constitution and the establishment of the FGS in 2012. This groundwork laid the foundation for the creation of the Federal Member States (FMS) based on pre-1991 boundaries. (Davies et al., 2023c)

Following this, Puntland became an FMS in 2012, followed by Galmudug, Jubbaland, South-West, and Hirshabelle over the next four years. The described FMS are clearly illustrated in Figure 2. Somaliland, however, refused to join the FGS’s federal framework, rejecting it outright (Tesema & Mohammed, 2025a). While the FGS and the international community regard Somaliland as an integral part of Somalia, in practice, the FGS lacks authority there, with Somaliland rejecting any budgetary, military, or administrative assistance from Mogadishu (Ferragamo & Klobucista, 2025a).

Article 1 of the Provisional Constitution of Somalia defines itself as a federal, sovereign, and united republic (Federal Republic of Somalia, 2012). Supporting this, UN bodies, such as Resolution 2067 (UNSC, 2012, p. 1), explicitly emphasise respect for Somalia’s sovereignty, unity, and territorial integrity. However, Somaliland’s claims to its own sovereignty have remained firm (Ferragamo & Klobucista, 2025b).

Figure 2: Federal Member States (FMS) of Somalia

Source. From Towards an Integrated Approach to Climate Security and Peacebuilding in Somalia, Broek et al., 2022, p. 4 (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361448396_Towards_an_Integrated_Approach_to_Climate_Security_and_Peacebuilding_in_Somalia).

After establishing a federal system of government, the next essential steps involved policymaking and then institutional development to formalise and implement the policies. Consequently, collaboration was encouraged between the FGS, the FMS, and international partners to support these complex processes. This led to the creation of the Somali Maritime Security and Resource Strategy 2013, which identified six key priority areas to combat piracy:

Maritime governance, maritime safety at sea, and naval response and recovery led by the International Maritime Organization (IMO); maritime law enforcement overseen by EUCAP and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC); maritime security managed by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM); and maritime economy coordinated by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (UNSC, 2013a, p. 4)

Somalia lacked the domestic capacity, so many programmes concentrated on building capacity in maritime governance, maritime security, and law enforcement. Various livelihood initiatives were also introduced to help Somalis secure sustainable employment opportunities. Most of these initiatives were implemented by the FAO, but their actual impact on employment and social security will be discussed in detail in the livelihood section.

The international organisations mentioned above, each responsible for a specific priority, supported the FGS and FMS in policy development, institutional strengthening, and implementation to tackle piracy comprehensively. In the case of Somaliland, coordination was not possible under this strategy, since it rejected it, considering itself separate from Somalia (UNSC, 2013b). If this remained the case, international organisations had to find alternative approaches, as Somaliland preferred autonomy; however, Somaliland later participated under the same vision for cooperation, recognising that maritime security was a shared concern—and still, this strategy remained the only platform for coordination between the FGS and Somaliland (UNSC, 2016a). It is also worth noting that many of the initiatives were carried out simultaneously and overlapped; the responsible agencies coordinated with one another to reinforce and avoid the replication of programmes that aimed to eradicate piracy (UN, 2014).

These policy efforts related to capacity building allowed a series of reforms in Somalia: Prisons were now refurbished, prosecutorial units were also being established, with Prosecutors and coast guards receiving extensive training to further boost capacities (UNSC, 2014a). To protect its waters and maritime resources legally, Somalia proclaimed its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (UNSC, 2014b).

According to the UNSC (2015a, p. 5):

Capacity-building and training programmes were implemented for fisheries observers and inspectors to strengthen the FGS’s ability to monitor, control, and oversee its waters, ensuring compliance by both national and international fishing vessels under local and international regulations. Technical and legal support were also provided to establish a federal Somali fisheries authority under the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources. This authority would enable Somalia to benefit from revenue generated through licences issued to foreign-flagged fishing vessels, while effectively monitoring its waters.

Additional technical assistance was provided to develop a registration system allowing governments, non-governmental organisations, and international naval missions to verify the identities of fishermen and protect their livelihoods.

The multitude of initiatives mentioned above demonstrates that Somalia was progressively building domestic oversight capacity, while establishing formal institutions to manage fisheries, with systems designed to distinguish legitimate fishermen from pirates.

In 2016, Somalia became the eighth member of the task force of Fish-i Africa, a group of countries in the western Indian Ocean that share information to combat and eliminate IUU fishing activities in the region. In other words, Somalia recognised early on that IUU fishing was a cross-border problem, and solving it required joint monitoring and cross-border enforcement.

Somalia has also become a party to the Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal Unreported Unregulated Fishing of the FAO—the first international treaty aimed at fighting illegal fishing. This agreement operates by requiring port states to inspect foreign vessels, deny port entry or services to those engaged in IUU fishing, while sharing information across. However, a weak legal framework and inadequate enforcement capacities have often hindered effective action. (UNSC, 2016b)

Somalia’s lack of a unified national coast guard has only worsened this inconsistent enforcement. While Puntland and Somaliland maintained their own maritime patrols, much of Somalia’s coastline remained under international naval surveillance. Although talks to formalise a national coast guard system were underway, significant resistance from the FMSs and Somaliland towards a centralised coast guard obstructed progress (UNSC, 2016c). They saw this step as a threat to their autonomy. Until 2018, establishing a unified coast guard was not feasible; however, a consensus was eventually reached to create a federal coast guard system, which would coordinate with the respective state guards instead of replacing them (UNSC, 2018a).

Despite these efforts, the issue of IUU fishing has persisted even after a decade, with it still reported in 2022, highlighting the fragmented nature of the enforcement. The same report, however, also notes improvements in Somalia’s prosecution capacity. Pirates who previously faced prosecution abroad are now convicted domestically. Out of the 28 pirates convicted since 2016, 27 serve sentences locally. Nevertheless, Somalia still lacks the capacity to prosecute pirate kingpins—those financing and organising piracy—and remains heavily reliant on international support for their prosecution. This means that domestic prosecution capacity has been developed. It can now convict and prosecute criminals within Somalia, but it still depends on international efforts for high-profile cases. It is important to recognise that, although some capacity has been built, the Coast Guard and maritime police still have limited capabilities; international partners, including EUCAP, UNSOM, UNODC, and FAO, continue to provide training, infrastructure, and legal support. (UNSC, 2022b)

A recurring issue throughout policymaking and implementation has been the governance-related disputes between the FGS and Somaliland. However, it’s not just Somaliland; disputes have also arisen with other Federal Member States over governance. The Provisional Constitution of Somalia does not clearly define fiscal responsibilities, resource management, or revenue-sharing mechanisms, leaving many powers ambiguous or overlapping (Tesema & Mohammed, 2025b). To address these issues, the Inter-Governmental Fiscal Forum (IGFF) was established under the World Bank’s Recurrent Cost and Reform Financing (RCRF) Project to promote cooperation between the FGS and FMS in managing resources and fiscal policy (Ministry of Finance, Federal Republic of Somalia, 2024). However, tensions regarding regional autonomy persist; for example, during the 2024 electoral reform dispute, disagreements between the FGS and Jubbaland led Jubbaland to suspend relations with the FGS (Tesema & Mohammed, 2025c). The Jubbaland regional government even amended its own constitution and held independent elections. This pattern of fragmentation was also evident during the implementation of a national coast guard policy, mentioned earlier.

By the late 2010s, Somali policymakers had already started to recognise that the Somali Maritime Security and Resource Strategy (2013) no longer reflected emerging national priorities. New issues—such as marine environmental degradation, youth unemployment, gender inclusion, and the need to shift focus from merely generating livelihoods to fully leveraging the blue economy—needed to be integrated into the agenda. Additionally, the 2013 Somali Maritime and Resource Strategy placed a heavy reliance on international actors. To address these issues, a National Maritime Strategy was drafted, but it is still in the consultation stage and has not been fully implemented yet, as reported by the UNSC (2022c).

Overall, after assessing a decade of reforms, it can be said that Somalia has successfully established a stable government. It can also be concluded that, to suit its divisive regional political landscape, the establishment of a federal system of government was, in fact, a good choice. It enabled Somalia’s political stability. However, this also came with drawbacks; though federalism was a pragmatic decision, it remained hampered by weak intergovernmental coordination between the FGS and the FMSs, including Somaliland’s continued secessionist stance.

Despite fragmentation and inconsistencies in enforcing these policies, the creation of a stable government allowed various state-building policies to be pursued. While these capacity-building efforts have created frameworks that function to some extent, they still require further development. Therefore, despite visible progress, Somalia’s state-building process remains ongoing, and continuous efforts and reforms will be crucial for future gains.

Livelihoods

Piracy, in the absence of a legitimate livelihood supporting Somalia’s coastal economy during its peak years, generated USD 339-413 million in ransoms between April 2005 and December 2012 (UNSC, 2013c). However, with the pirate economy no longer viable, reintroducing livelihood opportunities and ultimately revitalising the coastal economy became essential to alleviate economic stress. Since 2013, interventions have focused on transforming these conditions. FAO, responsible for restoring Somalia’s maritime economy, initiated efforts to revive artisanal fishing (UNSC, 2014c). This involved rehabilitating fish markets and boat-building facilities in coastal towns. Programmes targeting youth in high-risk coastal areas were launched to diversify livelihoods and offer alternatives to piracy recruitment (UNSC, 2015b). Despite these efforts, outcomes on the ground have been mixed.

The Somali Development and Reconstruction Bank (SDRB) reports that fish exports increased from USD 9.9 million in 2017 to USD 51.3 million in 2022, representing a nearly 400 per cent increase over five years. This indicates that Somalia’s fishing sector is recovering and generating revenue, consequently. Currently, about 30,000 full-time and 60,000 part-time fishers are employed, along with nearly half a million involved in processing, distribution, and equipment maintenance services. (SDRB, 2025a).

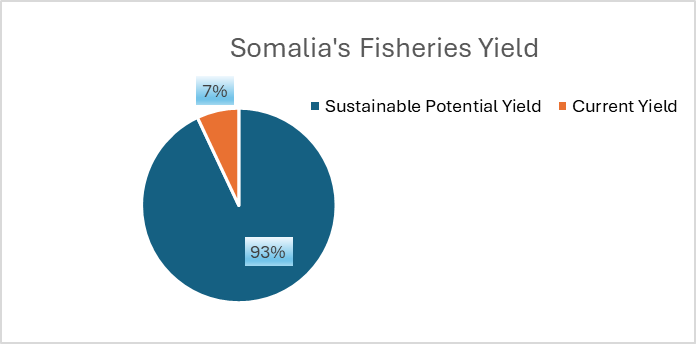

However, these gains remain modest compared to an estimated sustainable fishing yield of 380,000-500,000 tonnes per year. The most recent Somalia GLOBEFISH Market Profile data reports only 30,000 tonnes in fisheries and aquaculture production in 2020 (FAO, 2023). When put up against the 380,000-500,000 tonnes of sustainable potential yield, it only represents 6.5 to 7.5 % of the total. This leaves over 93% of the exclusive economic zone’s biologically sustainable yield unexploited, as illustrated in Figure 3.

If Somalia were able to harness even half of its sustainable yield, employment within the fishing and related industries could easily double. Not to mention, infrastructure gaps, such as the lack of cold storage and poor roads, lead to a 30-40% loss of catch before it reaches the market, significantly reducing earnings, making the sector further low-tapped (SDRB, 2025b).

Figure 3: Somalia’s Current Fisheries Yield Compared to Potential Sustainable Yield (2025)

Source. Compiled by the author from SDRB (2025)[4] and FAO (2023)[5].

If we zoom out slightly, Somalia’s attempt to revive artisanal fishing signals its need to create more employment opportunities; however, if the sector is not diversified and industrialised, the labour market will remain unable to absorb the growing youth population.

Somalia’s demography is among the youngest in the world, with over 60% of its population under 25. Among this group, only 34% participated in employment, compared to the global average of approximately 60%. The labour market is mainly driven by agriculture, but over the years, employment in this sector has declined from 36% in 2012 to 26% in 2022; meanwhile, service-based jobs increased from 50% to 56%. (ESCWA, 2025a; World Bank, 2024a)

This growth in the service sector and the decline in agriculture signal increased urbanisation. However, the shift has occurred without corresponding industrial development, as the industrial employment share rose only from 16% to 18%, a mere 2% increase. In support of this deduction, the Federal Republic of Somalia’s Ministry of Planning, Investment, and Economic Development (2025) also confirms the industrial sector’s underdevelopment. Industries generally provide more stable, secure, high-productivity jobs, and without them, the labour market will struggle to employ Somalia’s expanding youth population.

The Gjelsvik and Bjørgo (2012a) report:

A participant in the Alternative Livelihood to Piracy (ALP) project’s vocational skills training described difficulty finding a job after graduation. He estimated that only four people from his carpentry training group of fifteen were employed: “The market is somehow sleeping. There are a few carpenter workshops, which limit the number of employees, who are also few,” he explained. While participants valued the training for providing income opportunities and skills, many struggled to find stable employment after completing the programme. For example, five out of seven interviewees who underwent vocational skills training had some form of work. However, none had permanent jobs or sufficient income sources; therefore, possessing skills training does not guarantee employment in Somalia (p. 27).

These cases demonstrate that micro-level interventions will fail without macro-level industrial growth, and unemployment will persist without industries.

The lack of industries also contributes to high levels of informality. Around 82% of the employed population across all sectors is engaged in informal work, indicating that most jobs are informal, leaving the majority of the working population without worker protection, vulnerable to exploitation and poverty traps (ESCWA, 2025b). Informality in employment deprives the government of revenue needed for infrastructure, education, and services, as these workers do not pay regular taxes. Moreover, banks and investors are hesitant to extend credit to unregistered informal businesses, which poses a major obstacle for those seeking to scale up their microenterprises. Furthermore, Somalia remains largely a raw-materials exporter, and the absence of industrial activities such as fish canning, processing, and packaging means the country misses opportunities to capture greater value before export and to create additional employment.

The macroeconomic data give a picture of how Somalia’s livelihood landscape has changed little in the past decade. In 2012, the poverty rate was approximately 73%, and over the past decade, it has declined to around 54%, representing a nearly 20% decrease (UNDP, 2012; Haynes & Kotikula, 2025a).

On the surface, the decline may seem positive; however, 54% still means more than half of the Somali population lives in poverty. Poverty is disproportionately high among rural and nomadic households, affecting 64% and 71% of these populations, respectively. In contrast, the poverty rate among urban households is only 46%. This disparity indicates the increased vulnerability of rural and nomadic households, especially to economic stress. In Somalia, non-monetary poverty is higher than monetary poverty, which further worsens the situation. A person is considered non-monetary poor if they lack food security, have poor-quality housing, and lack access to key services such as education and healthcare. Here, non-monetary poverty was widespread, affecting three-quarters of the population in 2022. Once again, this was particularly common among the rural and nomadic population, where nearly every individual experienced non-monetary poverty. (Haynes & Kotikula, 2025b)

In the case of youth unemployment, the rate has hovered at approximately 34% in 2012. Over the past ten years, this figure too has remained mostly unchanged, fluctuating between 33% and 36% (World Bank, 2025b). For context, the global average youth unemployment rate has ranged from about 13% to 17% during the same period, meaning Somalia’s youth unemployment has been roughly double the global average (World Bank, 2025c).

If taken together, these figures suggest that, despite attempts to revive artisanal fishing and diversify livelihoods, Somalia’s livelihood scenario has not improved the lives of many. While poverty has declined, more than half of Somalia’s population continues to live below the poverty line, with the rural and nomadic population being the most vulnerable. And, when added with slow industrial growth, high informality, and high youth unemployment, it indicates that the economic stressors that once drove Somalis into piracy persisted.

Perception changes

As detailed previously, Somalia’s artisanal fisheries collapsed after 1991, creating deep social and economic grievances that contributed to the rise of piracy. Initially, pirates presented themselves as coast guards, using this justification for their actions, but over time, piracy became simply a means of livelihood. So, for piracy to be effectively discouraged, it must be framed as a negative practice, and the underlying grievances that make it seem justifiable must be addressed. Interestingly, as previously found, the issue of IUU fishing—the root of all this—remains unresolved.

IUU fishing continues, costing Somalia an estimated $300 million annually. This ongoing exploitation over the years has raised warnings over global tuna stocks, one of the most commercially valuable fish species, which could collapse by 2026. (ENACT Africa, 2025)

The UNSC (2022d) also reports that during November 2021 and October 2022, harassment of local shipping vessels by industrial vessels was increasingly reported by coastal communities (p. 6). This has left Somalia’s coastal communities frustrated, both socially and economically, and this frustration can be sensed from the local testimonies in the reporting done by Al Jazeera (2025a):

The trawlers come here and take everything from our seas. Fish, lobsters, nothing is spared, a fisherman from Puntland under the alias Liban Hassan, told Al Jazeera. The ships are visible from the shores of Eyl, while locals are forced to watch in anger as their oceans are polluted and stocks are depleted. What it would take 100 fishermen to capture in six months, trawlers can catch in a single day, and we’ve seen it with our own eyes, Liban said.

Mohamud Khalid Hassan, a town elder in Eyl, also told Al Jazeera at the time: When we stand on the shores of Eyl at night, we see lights everywhere, even though darkness is all around us, the sea is shining and you’d assume you are in Mogadishu with all these bright lights but you’re not, and these lights are from the trawlers pillaging our sea, said Mohamud, the elder. They (trawlers) get so close to shore when they’re looting fish, and they’re armed. All we can do is stand on shore and watch as it happens. We are powerless.

However, despite this issue remaining unresolved, the perception of piracy did change after 2012/13. This can be traced in a survey by UNODC (n.d.a) of 66 prison inmates who came from a wide range of locations in Somalia:

Prisoners were asked if they knew anyone who had stopped being a pirate. For those who did, family and community pressure were identified as the main reasons: in the Seychelles, 20 out of 21 prisoners cited this as why people left piracy. In Puntland, 5 of the 10 individuals identified by inmates as having ceased piracy were reported to have left due to family or community pressure, including one prisoner who said that the former pirate’s family had physically removed him from the group and taken him to a rehab centre. In Hargeisa, prisoners reported community and family pressure along with economic success as the two key reasons why people abandoned piracy. The Hargeisa interviewer stated that the communities are losing too many men (young men) to piracy, due to arrests, imprisonment, being lost at sea, etc. So, families are beginning to fear losing their kin and do not want them to go to sea.

However, it is worth noting that these pirates also testified that piracy was done more out of desperation for a livelihood, and they do not seek to police the waters, but would go to lengths, even taking up the government’s job and responsibility instead, if they failed to. (p. 3)

The shift in perception can be traced not only from these pirate prisoners’ testimonies but also in other Somali stakeholders.

For example, Osman Yusuf, a conservationist and leader of the fishing industry, remarked, in reference to the sudden re-emergence of piracy despite the several international strategies undertaken to eradicate it, stated: It is ironic that piracy has resurged, which will have a significant impact on our fishing activities in these waters. (Africanews, 2025a)

Many prisoners also revealed that they had originally gone to sea as fishermen, which raises questions about potential mishaps in some cases and explains why renewed piracy incidents are viewed as a threat to legitimate maritime livelihoods (UNODC, n.d.-b, p. 2). Similarly, Osman Abidi, a local fisherman, reported that piracy had already begun fuelling fear and stigma within coastal communities, as local fishermen risk being confused with pirates (Africanews, 2025b). A recent case also confirms the negative shift, where a Chinese trawler off the coast of Somalia was hijacked, and the local young fishermen involved in the hijacking refused to be labelled as pirates (Al Jazeera, 2025b).

Overall, these local testimonies reveal that in the past decade, the perception of Piracy in the coastal communities has become quite negative. The prosecution of pirates over the years has primarily aided in this change of view, with it now associated with stigma, fear, and a threat to fishing livelihoods. This negative perception has deterred the locals from participating in piracy; yet, still, for many, it becomes a coerced choice born out of systemic injustices, regardless of the negative social stigma currently attached to it.

Adaptations

Following the increase in international naval patrols against piracy, engaging in piracy was no longer a lucrative endeavour. Pirates who lost their source of livelihood needed to find ways to sustain themselves. Although initiatives to rehabilitate Somalis were underway, they could not be implemented immediately. The rehabilitation process involves several steps that require time, from planning and execution to achieving results. Rehabilitation, after all, does not happen overnight. With the sudden loss of income and no immediate alternatives available, there is a chance that some pirates may have turned to other illicit activities. Excluding individual reactionary fishermen’s pirate activities, piracy was an organised crime, a business with proper organisers and financiers—what happened to them? There is also a possibility that others shifted toward legitimate means of livelihood in response to negative community perceptions over time.

The UNSC (2015c), during the reporting period between 2014 and 2015, reported that, despite piracy-related crimes being reduced, trends in crimes related to human trafficking, smuggling, and drug trafficking increased suddenly. The UNSC (2018b) also reports that, between the years 2017 and 2018, 5 pirate attacks happened, with one incident being linked to Al-Shabaab. Confirming this suspicion of their adaptation, UNSC (2021) and UNSC (2022e) reports that Somali pirate networks have shifted away from piracy into other, less risky activities, retaining their networks, skills, and equipment, and they could turn back to piracy if the opportunity arises.

Taken together, these accounts show that pirates have adapted towards other illicit practices, where enforcement is relatively weaker. The networks of pirate financers and organisers, along with infrastructure, remain intact, and they have merely shifted away from piracy but are poised to resume if enforcement declines. There is even the possibility of their integration with extremist groups, as some attacks have been linked to Al-Shabaab, risking a blurring of lines between piracy and terrorism that further complicates the situation.

However, UNODC (n.d.c.) reports that some pirates quit piracy once they have earned enough, with many attempting to invest in other ventures. Many former pirates also disengaged from piracy voluntarily, as Gjelsvik and Bjørgo (2012b) report; many did so due to family and community pressure to live an honest life, for example:

The father of this young ex-pirate believed piracy was a dangerous activity and advised him to change his way of life. To stop his son from rejoining the group or other armed factions, he arranged for him to be relocated. My father sold some camels so I could get transport to Nairobi. I was very happy because being a pirate was not a good life. Even religion does not permit it, he quoted. (p. 24)

These accounts suggest that, contrary to the assumption that all pirates might have diversified into other illicit practices, many have, in fact, rehabilitated themselves with legitimate activities later.

Findings

In terms of governance, although a federal government has been established, providing relative political stability, the intergovernmental coordination has remained weak. The state-building policies in Somalia also remain ongoing. Although these policies have built some institutional capacity, they still require continuous effort to produce genuine results. Economic stressors also persist. Youth unemployment has shown little change over the past decade, while livelihood diversification initiatives have created jobs, the lack of industrialisation has left livelihoods largely informal and insufficient.

In terms of community perceptions of piracy, although it has become negative, deterring further participation, the primary grievance—IUU fishing, that originally drove coastal communities to piracy, is unresolved. Recent cases and testimonies analysed previously revealed that some occasional hijacks off the coast of Somalia were, in fact, led by local fishermen on foreign fishing trawlers involved in IUU fishing.

Many pirates have adapted by diversifying into other illicit activities, with some even linking to Al-Shabaab. Their underlying networks and infrastructure remain intact, merely shifting focus to other means since piracy could no longer be considered “easy money.” If these structures are not dismantled, there remains a risk that piracy could revive if its environment again becomes conducive to piracy.

Overall, when considering all the domains together, the decade-long decline in piracy has been fragile and has mainly been suppressed rather than fully resolved. International naval deterrence was initially the primary factor driving the decline. However, ongoing state-building efforts have also contributed somewhat to maintaining this equilibrium, especially as Somalia has become politically less chaotic, with domestic institutional capacities, such as prosecution, having improved relatively. However, many other departments involved in rehabilitation still lack capacity, leaving core grievances, such as IUU fishing and economic desperation, unresolved. In fact, rising pirate incidents have become a threat to local livelihoods, which can further worsen the existing economic stress.

Increased deterrence—both international and domestic—remains the primary factor in the decline of piracy, with a parallel negative perception being a byproduct of this. This has further contributed to the decline. And if this deterrence weakens, piracy’s resurgence could quickly happen again in Somalia as the pirate networks remain. This makes the decline unsustainable or not durable, as the change has been driven by the fear of prosecution primarily rather than by completely addressing the root causes, which forces piracy to become an option for sustenance in the first place.

Policy Recommendations

The following are some policy recommendations that could aid in solving piracy based on the issues identified in the earlier sections:

- The main challenge for Somalia is creating stable and reliable employment. The ongoing issue of youth employment indicates that diversification efforts, without industrialisation, cannot manage the growing youth population. Without industrialisation, jobs will mainly be short-term, inadequate, and informal. Industrial growth in the region has remained limited over the past decade; the Somali government must therefore identify the reasons for this slow progress and implement programmes that can attract investors and support emerging small businesses and budding entrepreneurs.

- Engagement with the FMSs and Somaliland has been the main obstacle to governance for the FGS. Therefore, strengthening policies and institutions to enhance federal-state relations is critically important and must be prioritised immediately. Renegotiating and redefining boundaries regarding authority is also essential to minimise disputes. Forums and bodies similar to the IGFF must be established where these disputes can be negotiated to reach a consensus, and which can be materialised later. The fragmentation, however, is also driven by the mindset of “us vs them”; therefore, to help mediate this regional divisiveness, fostering national unity by promoting a single Somali identity—emphasising shared history and culture through textbooks, media, films, sports, national festivals, and religion—can be beneficial in the long term.

- Efforts at state-building are still ongoing; therefore, deterrence can’t weaken. In 2022, international naval patrols ceased operations just within the Somali territorial waters out of respect for Somalia’s sovereignty, as covered in the introduction, and since then, the pirate incidents have increased. To mitigate this gap, Somalia should formally collaborate through fair diplomatic agreements for joint training and patrols. However, it is advised that while pursuing such initiatives, it should be kept in mind that Somalia’s maritime domain should not become a playground for global powers. The Gulf of Aden, being of strategic importance, requires such policy frameworks to be carefully balanced to prevent foreign militarisation in Somali waters and avoid becoming entangled in external rivalries driven by foreign national interests.

- IUU fishing did not cease. The action against piracy could work because piracy was framed as a global threat, “a security issue”. If IUU fishing were framed in the same way—since it fuels piracy and conflict—the UN resolutions could also authorise enforcement against it under existing international maritime security missions. This would also be particularly beneficial, as previously discussed, given that the cross-border agreements Somalia has signed to address IUU, which often fail due to weak enforcement, could coordinate to share information on identified foreign trawlers engaged in IUU with the international naval patrols. This would help Somalia to strengthen its enforcement.

- The grievances of the local fishing community, particularly due to IUU fishing and their enthusiasm to protect their waters, can also be channelled positively. These local fishermen and stakeholders can play a vital role in mitigating the logistics gap, detecting and identifying these vessels, as they possess valuable knowledge about their patterns and frequent locations. Most importantly for Somalia, rebuilding trust in the system among the locals is crucial to prevent them from taking the law into their own hands. This kind of local involvement can partially restore a sense of inclusion and faith among the coastal communities, reducing reactionary pirate activities by fishermen. To further deepen the trust, successful prosecutions can be released and distributed to the public through the media. However, in the long run, Somalia must further develop its capacity to detect, deter, and prosecute these foreign trawlers, which would continue to strengthen locals’ trust in the government and institutions.

- Piracy also threatens local coastal livelihoods. With fishermen mistaken for pirates, local communities begin to see fishing as risky, increasing their economic hardship. Although FAO has issued, as previously noted, identification cards for these fishermen, the fear persists, reflected in the local testimonies. To address this fear, awareness campaigns should be developed and launched to help coastal communities prevent unfair detention. A simple toolkit can be distributed to inform them of the dos and don’ts. Of course, for this to be effective, the Somali authorities must ensure these prescribed dos and don’ts are systematically enforceable. It is also necessary to look into whether these identification cards are serving their intended purpose and whether locals are benefiting from them. And if these misidentifications continue to occur, reforms or alternatives should be sought without delay.

- Pirate groups have adapted to other illicit activities, with some even linked to terrorism. With the increasing hybrid nature of these crimes, piracy laws need to be revised to include broader forms of criminal activity, while ensuring piracy and terrorism are not conflated. For these established pirate groups, piracy is a business; therefore, the focus should shift more towards the financiers and the organisers who mobilise it—for completely uprooting piracy—rather than merely prosecuting foot pirates on the sea.

Conclusion

Since core grievances—both economic and social—with pirate networks persist even after a decade of state-building efforts, it offers a reasonable explanation for the 2023 resurgence of piracy, especially as deterrence weakened in Somalian waters. This paper’s findings align with previous scholars’ conclusions that the primary reason for piracy’s decline was deterrence, since state-building has lagged. However, it should not be ignored that these same efforts, although lagging, have also helped create a more politically stable Somalia, which indirectly contributed to somewhat maintaining this decline.

Nonetheless, piracy did not end; it was only suppressed through deterrence, not eradicated. Deterrence alone is a fragile solution because, if it breaks down, piracy can resurface if the environment is conducive. This underscores the importance of a development-oriented approach to solving piracy, which should never be ignored. In Somalia’s case, deterrence should be framed as a temporary measure, a supportive solution, something that helps buy time for structural change, and definitely should not be treated as a replacement.

Therefore, this paper’s findings indicate that for the decline to be sustainable and durable, addressing core grievances and dismantling pirate networks through “state-building efforts” must be at the forefront, with it being the primary driver of change.

The scholarly contribution of this paper lies in broadening the understanding of the decline of piracy by going beyond the simple deterrence-only explanations commonly presented. It advances knowledge on the sustainability of the decline after 2012 and provides a possible reasoning for piracy’s re-emergence by thoroughly examining state-building efforts in Somalia. It closely analyses governance, institutional reforms, current community perceptions, and pirate adaptations for their contribution. Additionally, this study also challenges the scholarly view that deterrence alone ended piracy, highlighting that piracy has not entirely ceased. The study presents deterrence as a supportive measure rather than a complete solution and offers policy recommendations to address the issues identified through reforms.

Future research should investigate why industrialisation is underdeveloped in Somalia and explore ways to bridge this gap, thereby creating more livelihood opportunities that support upward mobility among residents. To sustain coastal communities, further research could focus on developing the blue economy through industrialisation. It is important to note that, while pursuing such research, the analysis, findings, and recommendations should be made with consideration for maintaining ecological integrity.

Title Image Courtesy: UN News

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and the Defence Research and Studies

References

[1] See FAO (2005) at: https://www.fao.org/fishery/docs/DOCUMENT/fcp/en/FI_CP_SO.pdf for additional details.

[2] See UNEP (1987) at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/9701/Coastal_marine_environmental_problems_Somalia_rsrs084.pdf for additional details.

[3] Hansen (2009) at: https://oda.oslomet.no/oda-xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12199/5640/2009-29-ny.pdf for additional details.

[4] See SDRB Article 2025 at: https://sdrb.gov.so/somalias-fisheries-sector/ for additional details.

[5] See FAO Report 2023 at: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/352bc896-4fe1-4e03-bda8-90198cb47e87/content for additional details.

More References

Africanews. (2025). Somali fishing industry leader says piracy puts livelihoods at risk. Africanews. Retrieved on 16 November 2025, from https://www.africanews.com/2025/11/07/somali-fishing-industry-leader-says-piracy-puts-livelihoods-at-risk/

Al Jazeera. (2025). ‘We’re not pirates,’ say hijackers who seized Chinese ship off Somalia coast. Al Jazeera Features. Retrieved on 16 November 2025, from https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2025/1/15/were-not-pirates-say-hijackers-aboard-chinese-ship-off-somalia-coast

Berube, C., & Murphy, M. N. (2008). Small boats, weak states, dirty money: Piracy and Maritime terrorism in the modern world. Naval War College Review, 62(4). Retrieved August 20, 2025, from https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol62/iss4/14

Broek, Emilie & Hodder, Christophe. (2022). Towards an Integrated Approach to Climate Security and Peacebuilding in Somalia. Retrieved on October 17, 2025. doi:10.55163/TUAI7810.

Bueger, C. (2013). Practice, Pirates and Coast Guards: the Grand Narrative of Somali piracy. Third World Quarterly, 34, 1811–1827. Retrieved on 18 August 2025. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.851896

Davies, F., Jama, M. Y., Watanabe, M., & Bhatti, Z. K. (2023). Local Governments and Federalism in Somalia: Fitting the Pieces Together. World Bank. Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099031224

Djama, A. D. (2011). The Phenomenon of Piracy off the Coast of Somalia: Challenges and Solutions of the International Community. United Nations–Nippon Foundation Fellowship Programme. United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS). Retrieved August 19, 2025, from https://www.un.org/depts/los/nippon/unnff_programme_home/fellows_pages/fellows_papers/djama_1112_djibouti.pdf

Elagab, D. O. (2010). Somali Piracy and International law: Some aspects. Australian and New Zealand Maritime Law Journal, 24. Retrieved August 18, 2025, from https://maritime.law.uq.edu.au/index.php/anzmlj/article/view/1652/1512

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. (2025). Elevating the talent pool in Somalia: A labour market analysis. Beirut: United Nations. Retrieved on November 7, 2025, from https://www.unescwa.org/publications/elevating-talent-pool-somalia-labour-market-analysis

ENACT Africa. (2025). Illegal yellowfin tuna fishing exposes gaps in Somalia’s maritime security. ENACT Observer. Retrieved on November 15, 2024, from https://enactafrica.org/enact-observer/illegal-yellowfin-tuna-fishing-exposes-gaps-in-somalia-s-maritime-security

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States. (2005). Fishery Country Profile: the Somali Republic. Retrieved August 30, 2025, from https://www.fao.org/fishery/docs/DOCUMENT/fcp/en/FI_CP_SO.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2023). GLOBEFISH market profile: Somalia. Rome: Author. Retrieved on November 7, 2025, from https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/352bc896-4fe1-4e03-bda8-90198cb47e87/content

Federal Republic of Somalia. (2012). Provisional Constitution of the Federal Republic of Somalia. Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://hrlibrary.umn.edu/research/Somalia-Constitution2012.pdf

Ferragamo, M., & Klobucista, C. (2025). Somaliland: The Horn of Africa’s breakaway state. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved November 2, 2025, from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/somaliland-horn-africas-breakaway-state

Gjelsvik, I. M., & Bjørgo, T. (2012). Ex-pirates in Somalia: Processes of engagement, disengagement and reintegration. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 13(2), 94–114. Retrieved on 18 November 2025. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14043858.2012.729353

Hansen, S. J. (2009). Piracy in the Greater Gulf of Aden: Myths, Misconceptions and Remedies. Oslo: Institute for Urban and Regional Research. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://oda.oslomet.no/oda-xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12199/5640/2009-29-ny.pdf

Hodgkinson, S. L. (2013). Current Trends in Global Piracy: Can Somalia’s Successes Help Combat Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea and Elsewhere. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law, 46(1). Retrieved August 18, 2025, from https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil

Haynes, A. P. F., & Kotikula, A. (2025, April 30). Five facts about poverty in Somalia. Africa Can End Poverty (World Bank Blogs) World Bank. Retrieved on November 13, 2025, from https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/africacan/five-facts-about-poverty-in-somalia-afe-0425

Ingiriis, M. H. (2013). The history of Somali piracy: From classical piracy to contemporary piracy, c. 1801–2011. In D. Vidas, & P. Jokstad (Eds.), Law of the Sea in Dialogue. Brill Nijhoff. Retrieved on 27 August 2025. doi:10.1163/9789004255210_019

Jakobsen, P. V., & Henningsen, T. B. (2024). Success defying all expectations: How and why limited use of force helped to end Somali piracy. Journal of Strategic Studies, 47(2), 263–287. Retrieved on 20 August 2025. doi:10.1080/01402390.2023.2227356

Karawita, A. K. (2019). Piracy in Somalia: An Analysis of the Challenges Faced by the International Community. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, 23(2), 102-119. doi:10.22146/jsp.37855

Madsen, J. V., & Kane-Hartnet, L. (2014). Towards a regional solution to Somali piracy: challenges and opportunities. Air & Space Power Journal – Africa & Francophonie, 67–79. Retrieved August 25, 2025, from https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ_French/journals_E/Volume-05_Issue-3/Madsen_Kane_e.pdf

Ministry of Finance, Federal Republic of Somalia. (2024). Strengthening fiscal cooperation and reform: The role of the Finance Ministers’ Fiscal Forum in Somalia’s governance. Retrieved on November 3, 2025, from https://www.hiiraan.org/news4/2024/Aug/197422/strengthening_fiscal_cooperation_and_reform_the_role_of_the_finance_ministers_fiscal_forum_in_somalia_s_governance.aspx

Ministry of Planning, Investment, and Economic Development, Somalia. (2025). Somalia economic outlook: 2nd edition. Mogadishu: Author. Retrieved on November 5, 2025, from https://mop.gov.so/wp-content/uploads/PDF/SOMALIA%20ECONOMIC%20OUTLOOK%202nd%20Edition%20Last%20Update.pdf

Møller, B. (2009). Piracy, Maritime Terrorism and Naval Strategy. Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS). Retrieved August 15, 2025, from https://hdl.handle.net/10419/59849

Somali Development and Reconstruction Bank. (2025). Somalia’s fisheries sector: A primer on the sector. Mogadishu: Author. Retrieved on November 6, 2025, from https://sdrb.gov.so/somalias-fisheries-sector/Tesema, D., & Mohammed, Z. (2025, January 14). Federal feud: Escalating tensions between

Somalia’s federal government and Jubaland. Good Governance Africa. Retrieved November 4, 2025, from https://gga.org/federal-feud-escalating-tensions-between-somalias-federal-government-and-jubaland/

United Nations. (2014). Security Council renews action to fight piracy off Somali coast, calling for deployment of vessels, arms, military aircraft (SC/11643). Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. Retrieved on October 24, 2025, from https://press.un.org/en/2014/sc11643.doc.htm

United Nations Development Programme. (2012). Somalia Human Development Report 2012: Empowering youth for peace and development (Factsheet). Mogadishu: Author. Retrieved on November 12, 2025, from https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/HDR-Somalia-Factsheet-2012-E.pdf

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2024). Navigating Troubled Waters Impact to Global Trade of Disruption of Shipping Routes in the Red Sea, Black Sea and Panama Canal. Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/osginf2024d2_en.pdf

United Nations Environment Programme. (1987). Coastal and Marine Environmental Problems of Somalia. Retrieved August 30, 2025, from https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/9701/Coastal_marine_environmental_problems_Somalia_rsrs084.pdf

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (n.d.). Somali prison survey report. Retrieved on 15 November 2025, from https://www.unodc.org/documents/Piracy/SomaliPrisonSurveyReport.pdf

United Nations Security Council. (2012). Resolution 2067 (2012). New York: United Nations. Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://undocs.org/S/RES/2067(2012)

United Nations Security Council. (2013). Report of the Secretary-General on the situation with respect to piracy and armed robbery at sea off the coast of Somalia (S/2013/623). Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/759590?ln=en&v=pdf

United Nations Security Council. (2014). Report of the Secretary-General on the situation with respect to piracy and armed robbery at sea off the coast of Somalia (S/2014/740). Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/781350?ln=en

United Nations Security Council. (2015). Report of the Secretary-General on the situation with respect to piracy and armed robbery at sea off the coast of Somalia (S/2015/776). Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/808135?ln=en

United Nations Security Council. (2016). Report of the Secretary-General on the situation with respect to piracy and armed robbery at sea off the coast of Somalia (S/2016/843). Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/844765?ln=en

United Nations Security Council. (2018). Report of the Secretary-General on the situation with respect to piracy and armed robbery at sea off the coast of Somalia (S/2018/903). Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1647930?ln=en

United Nations Security Council. (2021). Report of the Secretary-General on the situation with respect to piracy and armed robbery at sea off the coast of Somalia (S/2021/920). Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3947157?ln=en

United Nations Security Council. (2022). Report of the Secretary-General on the situation with respect to piracy and armed robbery at sea off the coast of Somalia (S/2022/819). Retrieved October 26, 2025, from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3993514?ln=en

World Bank. (2025a). Labor force participation rate, total (% of total population ages 15+) (modelled ILO estimate). Retrieved on November 5, 2025, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.ZS

World Bank. (2025b). Unemployment, youth total (% of total labour force ages 15–24) (modelled ILO estimate) – Somalia. World Development Indicators. Retrieved on November 10, 2025, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS?locations=SO

World Bank. (2025c). Unemployment, youth total (% of total labour force ages 15–24) (modelled ILO estimate). World Development Indicators. Retrieved on November 10, 2025, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS