Over the past two decades, the Indian Ocean region has witnessed a noticeable expansion in transnational organised crime networks, particularly those associated with maritime narcotics trafficking and illicit arms movement. Among the figures frequently mentioned in law-enforcement and intelligence discussions is an alleged trafficker known as Haji Salim. While public information about his activities remains fragmented, enforcement records and investigative reporting suggest that ‘Narco-terror’ networks linked to his name may have played a significant role in shaping maritime trafficking routes connecting South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa. This article examines the alleged evolution of the Salim network, its operational mechanisms, and its broader implications for regional security and counter-terrorism efforts. By analysing publicly available enforcement disclosures and investigative case material, this study aims to situate the network within the wider geopolitical and socio-economic environment that enables maritime organised crime.

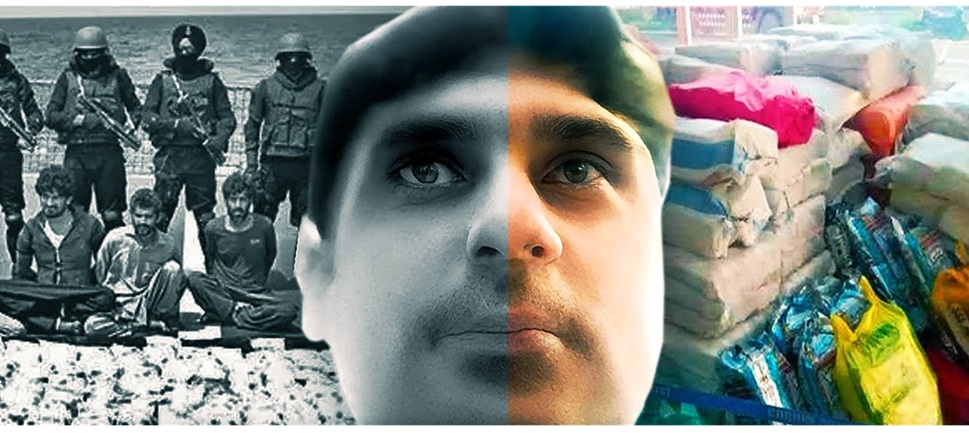

Haji Salim PC: YouTube

Introduction: Maritime Crime in a Changing Security Environment

The Indian Ocean has historically functioned as a vital corridor for global commerce, connecting major trade centres across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. However, the same maritime connectivity that sustains legitimate economic activity has also created opportunities for illicit trafficking networks. Vast coastlines, uneven maritime surveillance infrastructure, and overlapping legal jurisdictions have historically allowed criminal organisations to operate with relative mobility.

In recent years, enforcement agencies across South Asia have increasingly reported the emergence of coordinated trafficking networks that rely heavily on maritime routes. Within these investigative narratives, the name Haji Salim has surfaced repeatedly. Although definitive legal conclusions regarding his direct operational command remain complex, intelligence and enforcement reports have associated his alleged network with narcotics trafficking, arms smuggling, and suspected financial facilitation for extremist organisations.

Early enforcement references to Salim reportedly emerged during drug interdiction operations in the mid-2000s. However, by the early 2010s, authorities began identifying patterns suggesting that trafficking activities linked to his name had expanded geographically and structurally. Investigative agencies now view such networks as representative of a broader shift in organised crime, where leadership structures rely on distributed operational frameworks designed to minimise direct exposure.

Maritime Narcotics Trafficking: Operational Patterns and Logistics

One of the most distinctive features of trafficking networks associated with the Indian Ocean is their reliance on layered maritime logistics. Investigative case records indicate that narcotics consignments often originate from production hubs located near Afghanistan, which remains a significant source of global heroin production. From these inland supply zones, narcotics are transported to coastal processing and staging areas along Pakistan’s maritime belt.

From these staging zones, shipments are reportedly transferred onto deep-sea vessels operating beyond national territorial waters. The use of international maritime zones reduces the risk of early detection and complicates enforcement jurisdiction. Once positioned offshore, narcotics consignments are redistributed through smaller fishing vessels or commercial boats that transport shipments toward coastal entry points in India, Sri Lanka, and smaller island territories across the Indian Ocean.

This decentralised transport architecture appears designed to limit operational vulnerability. If one shipment is intercepted, higher-level organisational actors often remain insulated from direct law-enforcement identification. Interviews with maritime enforcement officials frequently emphasise that this layered system reflects a sophisticated adaptation to modern surveillance technologies and interdiction strategies.

The Narco-Terror Convergence: Criminal Enterprise and Violent Networks

Maritime interdiction operations over the past decade have occasionally uncovered consignments containing both narcotics and weapons. Although direct command relationships between trafficking networks and militant organisations are difficult to establish legally, security analysts increasingly view such recoveries as indicators of logistical convergence between organised crime and insurgent financing structures.

The economic scale of narcotics trafficking generates substantial financial resources, some of which may be redirected toward procuring arms or supporting extremist operations. This overlap blurs the traditional distinction between profit-driven criminal enterprise and ideologically motivated militancy. The resulting hybrid networks pose significant challenges for counter-terrorism agencies, as enforcement responses must address both criminal and security dimensions simultaneously.

Researchers studying insurgency financing have observed that organised criminal networks often provide logistical and financial services rather than direct operational integration with militant groups. Such transactional relationships allow extremist actors to benefit from established trafficking infrastructure while maintaining operational independence. The alleged Salim network appears to reflect this broader pattern of opportunistic collaboration.

Organised Crime Alliances and Financial Protection Mechanisms

Another factor contributing to the resilience of maritime trafficking networks is their reported interaction with established organised crime syndicates operating across South Asia and the Gulf region. Investigative reporting has suggested possible intersections between trafficking corridors attributed to Salim and networks historically associated with underworld actors based in Karachi and Dubai.

These alliances serve several strategic functions. They provide access to money-laundering channels, secure logistics networks, and protection within diaspora-linked commercial ecosystems. Informal financial transfer mechanisms such as hawala networks reportedly play a central role in sustaining these financial flows. Because such systems operate outside conventional banking oversight, tracing illicit capital becomes considerably more complex.

Financial centralisation appears to be a defining feature of many transnational trafficking organisations. While operational activities are often distributed across multiple cells, financial decision-making typically remains concentrated among senior network coordinators. This structure enables strategic planning while preserving organisational continuity even when individual operatives are arrested.

Enforcement Operations and Legal Challenges

Law-enforcement agencies across South Asia have intensified maritime interdiction operations in response to the growth of trafficking networks. Several high-profile seizures have involved fishing vessels intercepted in the Arabian Sea carrying large quantities of heroin and, in certain cases, sophisticated firearms.

One notable case involved the interception of a Sri Lankan fishing vessel suspected of transporting narcotics and weapons intended for distribution across South Asia. Court proceedings associated with the case highlighted the complex investigative process required to establish transnational trafficking linkages. The seriousness of such investigations is reflected in judicial decisions that frequently deny bail to individuals charged under national security provisions.

Despite these enforcement successes, dismantling leadership structures remains difficult. Intelligence assessments suggest that senior coordinators of transnational trafficking networks often operate from jurisdictions where extradition and enforcement cooperation face diplomatic and legal obstacles. Consequently, enforcement operations tend to disrupt logistical components rather than eliminate entire network hierarchies.

Recruitment Strategies and Socio-Economic Drivers

Trafficking networks operating across maritime environments frequently rely on recruitment strategies that target economically vulnerable coastal populations. Fishing communities, maritime labourers, and small-scale transport operators often face unstable income conditions, making them susceptible to financial incentives offered by trafficking intermediaries.

Field research conducted by maritime security analysts suggests that participation in trafficking activities is typically motivated by economic survival rather than ideological alignment. This dynamic allows organised crime networks to maintain a steady operational workforce while reducing the risk of ideological infiltration that might attract heightened security attention.

In addition, governance gaps across certain coastal regions contribute to recruitment opportunities. Limited surveillance infrastructure, corruption vulnerabilities, and inconsistent inter-agency coordination create operational spaces that trafficking networks exploit by frequently modifying transport routes and logistical techniques.

Geopolitical and Security Implications

The expansion of transnational trafficking networks across the Indian Ocean represents a significant shift in regional security dynamics. Maritime narcotics trafficking now intersects with counter-terrorism policy, diplomatic cooperation frameworks, and economic security concerns related to global shipping corridors.

The Indian Ocean’s strategic position as one of the world’s busiest maritime trade routes increases the potential consequences of criminal network infiltration. Analysts have raised concerns that sustained collaboration between organised crime and extremist actors could prolong regional insurgencies and destabilise fragile coastal states.

Although intelligence-sharing initiatives among regional governments have improved in recent years, enforcement cooperation remains uneven. Differences in legal systems, investigative capacity, and political priorities continue to complicate unified counter-trafficking responses.

Conclusion: Adaptation and Persistence in Transnational Crime

The alleged network associated with Haji Salim illustrates how modern organised crime has evolved in response to globalisation, technological advancement, and shifting enforcement strategies. Maritime trafficking networks increasingly rely on decentralised operational cells, sophisticated financial management systems, and flexible recruitment models that allow them to adapt rapidly to interdiction pressure.

Efforts to dismantle such networks require a multidimensional policy approach. Strengthening maritime surveillance infrastructure, enhancing financial intelligence cooperation, improving international legal coordination, and addressing socio-economic vulnerabilities in coastal communities are crucial components of a comprehensive long-term counter-trafficking strategy.

As economic inequality, governance fragmentation, and geopolitical tensions persist across the Indian Ocean region, trafficking networks similar to those allegedly linked to Salim are likely to remain active. Addressing this challenge, therefore, requires not only criminal enforcement but also sustained structural reforms that reduce the underlying conditions enabling transnational narco-terror networks to flourish.

Title Image courtesy: Firstpost

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and the Defence Research and Studies. This opinion is written for strategic debate. It is intended to provoke critical thinking, not louder voices.

References

[1] NDTV, “Anti-drugs agency launches operation to track down ‘Lord of Drugs’ Haji Salim,” Nov. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ndtv.com

[2] India Today, “NCB operations and the hunt for Pakistan-based drug trafficker Haji Salim,” Nov. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.indiatoday.in

[3] The Week, “Who is Haji Salim? India’s search for the Pakistan-based drug trafficker with alleged underworld links,” Nov. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.theweek.in

[4] The Times of India, “Pak national linked to arms and drugs seizure off Lakshadweep, NIA tells Kerala High Court,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com

[5] The Times of India, “Arms seizure from Sri Lankan boat: Bail plea rejected in narco-terror case,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com

[6] Hindustan Times, “Investigators link drug trafficking network to terror financing activities,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.hindustantimes.com

[7] The New Indian Express, “Drug and arms smuggling routes through Sri Lankan maritime networks,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.newindianexpress.com

[8] Manorama Online, “Profile of Haji Salim and narco-terror activities targeting Indian maritime security,” May 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.manoramaonline.com

[9] South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), “Drug trafficking and terror financing networks in South Asia,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.satp.org

[10] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), “Afghanistan opium cultivation and regional trafficking routes,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.unodc.org

[11] Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, “Narco-terrorism and maritime security assessments,” Annual Security Report, 2024.

[12] Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB), Government of India, “Operation Sagar Manthan: Maritime drug interdiction overview,” 2024.

[13] National Investigation Agency (NIA), Government of India, “Court filings and investigation reports in maritime drug and arms seizure cases,” 2021–2025.

[14] Financial Action Task Force (FATF), “Money laundering and terror financing risks in South Asia,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.fatf-gafi.org

[15] International Maritime Organisation (IMO), “Maritime security and trafficking vulnerabilities in the Indian Ocean,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.imo.org