The audacious missile attack with by two Komar-class missile patrol boats on the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) destroyer Eilat on 21st Oct 67 heralded the arrival of the cruise missile in the naval battlefield space. Surface to Surface Missiles (SSMs) or Anti-ship Missiles (AShM), as they are popularly referred to, literally ushered a sea change in the way sea battles would be fought in the future. Since then, missiles have always been fired in anger in most engagements at sea.

A study of all the major naval battles fought since the first anti-ship cruise missile was fired in 1967, highlights the following:-

SSMs began to dominate the naval battlespace until the 90s. This is borne out by the deployment of SSMs in all the major conflicts during the period. These include the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971, the Arab-Israeli War of 1973, the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1987, which began as Operation Morvarid and later turned into the Tanker war1, the Falklands War of 1982, the Battle of Sidra in 1986, Operation Praying Mantis in 1988, and the Gulf War of 1991 (The Battle of Bubiyan).

Since 1991, there has hardly been any significant naval battle at sea between fleets. Most of the naval engagements have been limited to local skirmishes between minor warships generally ending in gun engagements. There were three exceptions. The first was the 2006 Lebanon War where the Hezbollah guerrillas fired a Silkworm missile at an Israeli warship off the shores of Lebanon and damaged it. The second was the Battle off the coast of Abkhazia in 2008 between Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet and the Georgian Navy, where a Georgian vessel was struck and sunk in 300 m of water by P-120 Malakhit (SS-N-9 ‘Siren’) missile, fired allegedly by the guided-missile corvette MRK Mirazh. The third was the Houthi forces firing two missiles(alleged silkworm) against USS Mason in Oct 2016, which fired 2 SM2 SAMs and 1 ESSM (all SAMs first time against actual threat since development). The skirmishes that ended in gun engagements were between the flotilla of South Korea and North Korea (First Battle of Yeonpyeong (1999), Second Battle of Yeonpyeong (2002) and Battle of Daecheong (2009)) and another skirmish between the flotilla of North Korea and Japan in what is classified as the Battle of Amami-Ōshima (2001).

Towards the end of the first decade of this century, the scourge of piracy again raised its ugly head with a large number of incidents off the horn of Africa. This rise of piracy changed the dynamics of the deployment of naval forces and also necessitated the recalibration of the weapons fitment onboard ships. Emphasis shifted to small calibre weapons like 12.7 mm and 20 mm guns, which were more optimised to engage the skiffs and small boats employed by the pirates.

However, this does not imply that SSMs have lost their significance or relevance in naval battles, as ships continue to be armed with increasingly sophisticated SSMs. Therefore, the need to evaluate the effectiveness of SSMs as a weapon is very much relevant today. However, due to limited naval engagements with missiles in recent times, we have to rely on historical data, to estimate the efficacy of SSMs. A study of SSMs engagements in naval battles undertaken by John Schulte2, examined historical data up to 1991, to determine the effectiveness of SSMs in naval warfare. This has been updated with subsequent missile engagements.

A total of 234 SSMs have been fired against targets during all naval engagements between 1967 and 2008. Of these, 125 SSMs managed to hit their target sinking 33 ships and putting 75 ships out of action. This data does not include missile firings in controlled environment routinely undertaken by navies using decommissioned ships or other such targets to evaluate missiles, train personnel and validate tactics and weapon systems.

Missiles have been fired on various types of targets like merchant ships, warships and in some cases against land targets. To make the analysis more focussed, based on the type of target engaged, the type of engagements has been classified into the following three categories – Undefended or Merchant ship, Warships in Lower Degree of Readiness and Warships in Higher Degree of Readiness.

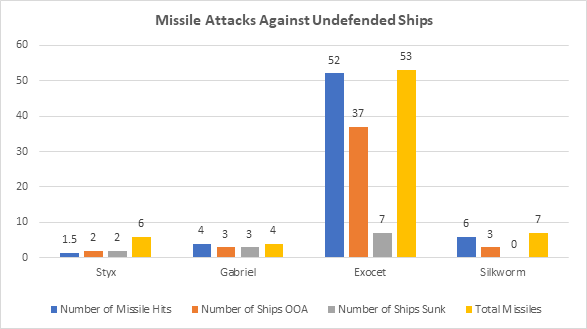

The first category is missile attacks on undefended targets. These ships, generally merchant ships, have no capabilities to detect (other than a visual alarm), engage or deceive an incoming missile. The merchant ships are also limited in their ability to manoeuvre away from the missile due to design limitations. 63 SSMs were fired against such targets. A majority of these have been the Exocet missiles fired during the Tanker War, against unprotected oil tankers and freighters. Although there are no exact numbers of missiles fired and hits, more than 500 merchant ships3 were attacked in the Persian Gulf, between 1984 and 1988. Iraq initiated 280 of these attacks while Iran launched 221 attacks. Iraq extensively employed the air-launched Exocet from 1984 when they acquired the Super Etendard aircraft with around 300 Exocet missiles from France4. During the Tanker war, it is estimated, based on data available for the year 1984 that 52 of 53 Exocet anti-ship missiles hit their targets, and 50 of the 52 hits detonated properly5. The Iranians relied on high-speed, heavily armed, small attack boats with several offensive weapons, including bow-mounted machine guns and Soviet-made rocket-propelled grenades6. They also employed a range of smaller payload weapons such as AS 12s and Mavericks, which caused little physical damage to ships, and it was only in ‘87 that they began to deploy the Chinese CSSC-2 Silkworm. However, there are 6 firings recorded between 1987 and 1988, when a cease-fire was brokered between the two belligerents. The last firing of a silkworm missile was in Oct 2016 7, against an unarmed HSV Swift leased by UAE. The details of the engagements are shown in figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Missile Attacks against Undefended Targets

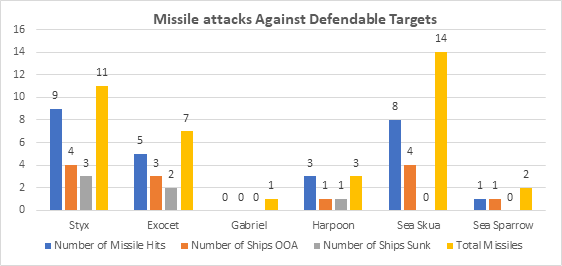

The second category of missile attacks are warships, which have the capability to engage or deceive an incoming missile but for various reasons are operating at lower levels of operational readiness and therefore do not employ available defence measures. It could be due to surprise, inattentiveness, or equipment malfunction.

The number of warships hit during wartime deployment runs contrary to the expectation that there would be higher levels of readiness and vigilance. A total of 38 missiles were fired against this category of ships of which 26 hit their target. A total of 6 ships were sunk and 13 were put out of action. This includes the famous attack Eilat in 67, missile attacks on Kahibar and Badr in Indo-Pak ’71, engagements during the Falklands war (Sheffield, Ambuscade, Avenger and Penelope), the infamous Stark incident, attack on Iranian warship Srihand during Op Praying Mantis, attacks by Lynx helicopters on the Iraqi fleet during the Battle of Bubiyan, the Saratoga incident of firing on Turkish ship Mauvenet during a NATO exercise and the silkworm missile attack on Israeli navy ship Hanit during the Lebanon war in 2006. Many of these attacks could be thwarted had appropriate measures been taken in time.

Figure 2 Missile Attacks against Defendable Targets

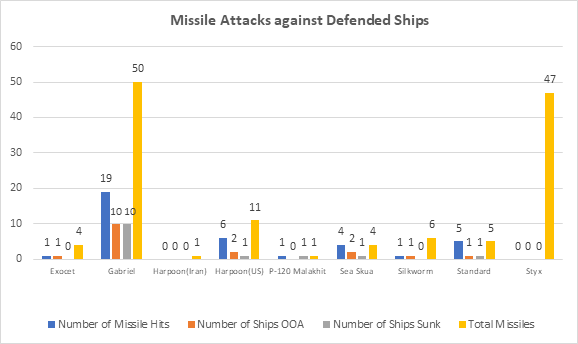

The third category of attacks is the warships, which were in a high state of readiness or alertness and therefore deployed all available resources including a hard kill and/or soft kill defences, ship manoeuvres to defeat incoming missiles. These are obviously the hardest targets to hit. Hard kill measures refer to Surface to Air Missiles, Medium-Range guns, Close-in Weapon Systems employed by the ship and the screen units of the Task Force. Soft kill measures refer to defeating an incoming missile, without destroying it, by the deployment of Chaff to break radar lock, deceive/seduce the incoming missile, jamming the homing head and manoeuvre to reduce RCS. The efficacy of this countermeasure is elaborated below:-

Softkill measures employed against anti-ship missiles were extremely successful, seducing or decoying every missile they were used against. In every engagement where a defender was alert and deployed softkill measures, missile salvos were entirely defeated. This is borne out during the naval engagements during the Arab-Israeli War (Battle of Latakia in 1973), Falkland War in 1982 and Op Praying Mantis in 1988, when chaff decoys were extensively deployed.

Hardkill measures were not as successful, with only one case confirmed during all these engagements. HMS Gloucester, using its Sea Dart system, shot down a Silkworm missile launched at the USS Missouri during Persian Gulf War (1990-1991). The SAM systems of that generation were manually controlled and relatively less effective than current generation SAM systems. During the attack on USS Mason in Oct 2016, 2 SM2 and 1 ESSM was launched against 2 silkworms missiles, in addition to softkill measures (Nulka decoys)8. However, more data is needed to assess the combat capabilities of modem hardkill systems.

Figure 3 Missile Attacks against Defended Targets

Defended targets are difficult to hit and destroy, as is evident from the number of missiles fired and the target destroyed. A total of 124 missiles were fired which resulted in 34 hits. A total of 14 ships were sunk and 17 were put out of action. As can be observed in Figure 3, during the Arab Israel war in 73, none of the forty-seven Styx missiles fired by the Syrian/ Egyptian navies against the Israeli warships found their target while nineteen of the fifty Gabriel missiles hit their targets. The Styx was rendered obsolete due to the technological advancements in soft kill measures like jamming and chaff and improvements in hard kill measures like Surface to Air Missiles(SAM). The more advanced Exocet and the harpoon had better hit probability.

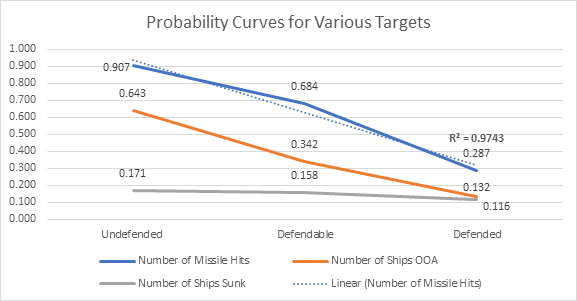

The historical missile hit probabilities are summarized in Figure 4 below. As is obvious, the probability of hit against an undefended large merchant target is high (.907), while that for a warship in action stations is low at 0.286. This implies that alert warships with good Anti-Missile Defence capability can bring down almost 3 of the 4 incoming SSMs. The low probability of ships being sunk by missiles in all the cases is relatively low. In case of undefended merchant ships (0.171), this is probably due to the large size of ships, the impact point of the striking SSM generally being above the waterline, the small size of the missile warhead and also in many cases the warhead not exploding. While in the case of warships, better damage control capability gives it greater survivability (.116). Analysis of missile hit data indicates that smaller cargo ships/tankers (between 13,000 to 30,000 tons displacement), resulted in 20% sinking, 60% major damage, and 20% minor damage. While in case of large tankers (70,000 to 300,000 tons displacement), did not result in sinking but 60% of the ships were heavily damaged, and 40% saw minor damage.

Figure 4. Probability of hit by the category

An analysis of the data and comparison of the probability of hits for different generations of SSMs reveals that the first generation SSMs like Styx and Gabriel had a probability of hit of 0.196 against defended ships, while in case of the relatively more modern missiles like Exocet and harpoon it is 0.438. Therefore, statistically the Exocet and Harpoon SSMs have more than a 50% edge of hitting a defended target compared to the older generation SSMs. This is with a caveat that assumes the defended ships have the same old hardkill and softkill measures. The dynamics will certainly change if the current developments in Anti-Missile Defence systems – SAMs and decoy systems are into account. However, that is another study.

The probability of hit determined above is based on actual field results and not on simulation studies. The data can be used to both by the attackers (SSM developers) and the defenders (ship designers) to improve their respective systems. The ship designers need to dwell on methods to improve survivability against SSM. These include improvements to sensors to enable early detection, classification and tracking of threats; improve soft kill weapons like Chaff and jamming systems; improve Air Defence weapons with greater range, better guidance(thereby enhance the probability of interception), tactical measures like mutual support and increase the number of defence layers with LRSAM, SRSAMS and CIWS missile/gun systems. This is to ensure that the Kp is reduced to < 0.3. On the other hand, SSM developers need to focus on enhancing features for better survivability of the missile and having a greater kill probability. This includes reducing RCS, flying low, increased speed, improvements to the seeker for better target detection and discrimination, use of terminal manoeuvres, etc. This is clearly seen from current developments. From an initial lot of four missiles (Styx and variants, Gabriel, Exocet and Harpoon) which were extensively used between the 70s and 90s, there are more than thirty different types of SSMs available today. The latest generation of sleek supersonic SSMs hardly bear any resemblance to their predecessors and are a far cry from the first generation Styx missiles, which were bulky and slow missiles with poor height keeping ability, primitive electronics and guidance systems and a large RCS. Technological advancements in aerodynamics, electronics and propulsion systems have produced a vast number of new intelligent missiles, which are more reliable, fly sea-skimming altitudes, and are highly manoeuvrable and accurate. The influx of supersonic missiles today and hypersonic missiles in the near future in the arena will further complicate the problem of effective anti-missile defence due to reduced detection ranges and drastically reduced reaction times.

In conclusion, the SSM has revolutionised naval warfare since its introduction in 1967. It will continue to dominate the naval battlespace as a very effective weapon against ships, including defended warships. A higher leakage rate will ensure that the threat is significant even for well-defended targets. The window of opportunity available to the defender to engage the incoming missile is constantly shrinking. The SSM will also continue to be the first choice of weapon against undefended merchant ships given the high probability of hit and the ability to put them out of action easily. Navies will have to invest heavily in improving the ship’s defensive firepower with better SAM and CIWS systems and also focus on survivability capability of ships if they are to survive in combat situations of the future.

Image Courtesy: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/&https://defencyclopedia.com/2014&https://defence.pk/&https://in.pinterest.com/pin

References

[1] “Tanker War” started when Iraq attacked the oil terminal and oil tankers at Kharg Island in early 1984 after declaring an “exclusion zone” for shipping around the Iranian oil port at Kharg Island in the northern sector of the gulf. It was conducted by both the belligerents – Iran and Iraq until 1988.

[2] Schulte, John C. An Analysis of the Historical Effectiveness of Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles in Littoral Warfare. Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, September 1994.

[3] O’Rourke, Ronald, “Gulf Ops,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 1989

[4] As per SIPRI Arms Transfers Database 300 Exocets were delivered to Iraq in 1983

[5] https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/exocet-combat.htm#

[6] https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1988/may/convoy-mission

[7] https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/IN10599.pdf

[8] https://news.usni.org/2016/10/11/uss-mason-fired-3-missiles-to-defend-from-yemen-cruise-missiles-attack

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies