The article seeks to examine the conditions under which the legacy cooperation continues to expand India’s strategic options, where trade, supply chains, and financial leverage are explicitly embedded in national security policy. This piece is intended as a continuation of the debate opened by Captain SS Parmar’s recent analysis published in DRaS about India–Russia maritime strategy and relations.

The above-mentioned analyses on India–Russia maritime relations have rightly foregrounded the historical depth and institutional continuity of this partnership. They trace how naval cooperation, shipbuilding, technology transfer, and operational trust evolved from Cold War imperatives into a multi-dimensional maritime relationship that has endured geopolitical change. That body of work usefully establishes the foundations of India–Russia maritime ties and explains why they remain embedded in India’s naval culture, force structure, and strategic memory.[1]

In the first decade and a half after Independence, India’s aircraft carrier, her frontline fighter complement, and major surface assets were largely acquired from the United Kingdom, including INS Vikrant and her British-origin carrier aircraft, even as a functional imperative saw India equip Vikrant with French-origin anti-submarine warfare aircraft. From the mid-1960s, however, a structural shift toward Soviet naval platforms began to take hold—most notably with the induction of submarines and specialised surface vessels—as Soviet support filled a critical capability gap at a time when Western technology denial constrained India’s options.[2]

This Soviet-centred phase was later complemented by selective Western submarine inductions, notably the HDW Type-209 boats and, more recently, the Scorpène class, as India progressively diversified its naval technology base. The legacy of the Soviet period nonetheless continued to shape the Indian Navy’s force structure, training culture, and operational thinking well into the post-Cold War era, even as evolving capability requirements and systems-integration demands drove a more plural, ecosystem-based approach to naval modernisation.

This essay proceeds from that foundation. It does not seek to revisit the historical narrative or reassess the value of the partnership as such. Instead, it asks a subsequent policy question that naturally follows: how should India’s maritime strategy interpret and deploy legacy partnerships in a contemporary environment increasingly shaped by economic coercion, transactional diplomacy, and networked maritime power?

The maritime domain confronting India today differs fundamentally from the one in which earlier strategic choices were made. Power at sea is now exercised not only through fleets and platforms, but through economics, networks, standards, finance, and regulatory leverage.[3] In this altered landscape, the central issue is no longer whether legacy partnerships remain relevant—they do—but whether they are being integrated with sufficient strategic discipline into a wider, future-oriented maritime strategy.

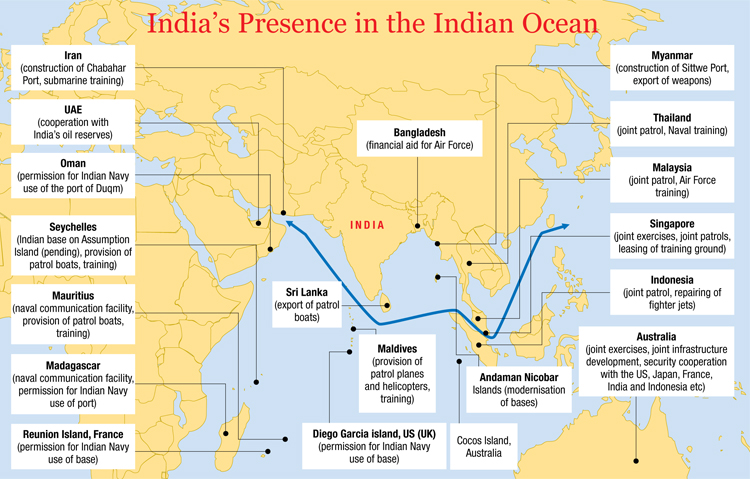

PC: Insights IAS

From Naval Cooperation to Maritime Strategy

A critical distinction must be made between naval cooperation and maritime strategy. Naval cooperation focuses on platforms, exercises, doctrine, and operational familiarity. Maritime strategy encompasses a far broader terrain: trade routes and port access; logistics, shipping, insurance, and finance; industrial supply chains and standards; data flows and regulatory regimes; and political signalling and economic leverage.[4]

In this expanded domain, bilateral naval legacies—however durable—represent only one component of national maritime power. A strategy that over-identifies maritime strength with naval history risks misreading how influence is now exercised at sea. It also risks underestimating the role of non-military instruments in constraining or enabling the use of naval force.[5]

For India, the practical implication is clear. Legacy partnerships, including with Russia, must be evaluated not only for their contribution to fleet composition or operational familiarity, but for how they position India within the wider architecture of maritime economics, regulation, and connectivity. Naval cooperation remains necessary; it is no longer sufficient.

Legacy Partnerships as Strategic Ballast

India–Russia maritime relations serve as strategic ballast today. They stabilise India’s force structure, preserve critical capabilities, and reinforce India’s long-standing emphasis on strategic autonomy. Submarine cooperation, nuclear propulsion experience, missile co-development, and decades of operational learning have all contributed meaningfully to India’s maritime capacity.[6]

This ballast provides continuity and confidence. It also offers India leverage in dealing with other partners by avoiding over-dependence on any single source of technology or support. In this sense, the relationship continues to deliver strategic value even as India diversifies its defence and maritime ecosystem.

However, ballast does not determine direction. A vessel steadied by ballast still requires a compass. The danger lies not in retaining legacy partnerships, but in allowing them to substitute for a forward-looking strategy. Treating historical comfort as a guide for future alignment risks locking India into patterns that no longer track the distribution of maritime power and economic coercion.

Capability Compulsion and the Indian Navy’s Western Turn

Over the past three decades, the Indian Navy has quietly but decisively shifted from a Russian-centric technological dependence toward a predominantly Western, mixed-ecosystem orientation. This change is visible across core operational domains: long-range maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare aircraft, multi-role naval helicopters, gas-turbine propulsion systems, submarine acquisition philosophies, ongoing realignments in carrier aviation, and the wider ISR, ELINT, and unmanned systems ecosystem.[7]

This was not a political or ideological reorientation. It was a response to a widening technology and integration gap as naval warfare became increasingly sensor-driven, network-centric, and data-intensive. Modern maritime operations demand persistent domain awareness, effective sensor–shooter separation, secure and interoperable data links, and consistently high availability in demanding operational environments.[8]

Russian naval platforms, while often robust and proven in operational use, began to diverge sharply across domains in their ability to meet these evolving requirements. The core issue was not platform strength in isolation, but Russia’s diminishing capacity—especially after the breakup of the Soviet Union—to deliver and sustain a complete, modern operational ecosystem.

Limitations in sensors, software architectures, networking, and, critically, through-life support became progressively harder to ignore. These gaps were temporarily mitigated through the integration of Western and Israeli sensors and networking solutions, alongside the development of indigenous space-based communications capabilities. However, such hybrid fixes could not substitute for the absence of a reliable, evolving Russian support and upgrade ecosystem.

It was this reality that ultimately drove the Indian Navy toward Western systems and Israeli sensor and hybrid networking solutions in critical domains, even as Russia remained important in submarines and legacy surface platforms. The transition reflected capability realism rather than alliance signalling. Faced with the demands of contemporary naval warfare, the Navy prioritised performance, reliability, and operational credibility over system origin.

The Paradox of Convergence and Coercion

This capability-driven convergence with Western systems has produced an unintended paradox. As the Indian Navy became more interoperable with Western navies, it also became more exposed to Western political expectations—particularly during periods of overt transactionalism, most visible in the current Trump era.[9]

The implicit assumption underlying such pressure is straightforward: if India operates Western-origin systems, benefits from Western interoperability, and participates in Indo-Pacific maritime frameworks, it should align economically and politically with Western preferences—especially with respect to Russian energy imports and legacy defence acquisitions. Maritime capability choices are thus read not merely as operational decisions, but as indicators of geopolitical loyalty.

This reading is reinforced by a long-standing view within Washington policy circles that arms transfers are instruments of strategy rather than export promotion. As several US strategic thinkers have argued, defence sales are conceived primarily as tools for shaping long-term alignment—embedding interoperability, influencing doctrine, and creating durable political convergence. This perspective is reflected both in US conventional arms-transfer policy and in the views articulated by figures such as Michael Pillsbury in published work and Track-2 engagements with Indian strategists during the mid-2010s. [10]

From India’s perspective, however, this assumption is flawed. The Indian Navy’s diversification was intended to reduce dependence on any single source, not to replace one dependence with another. Russian energy imports serve macroeconomic stability, inflation control, and energy security objectives. Legacy defence systems, including strategic air defence, addressed immediate capability gaps when viable alternatives were unavailable. [11] Neither choice was conceived as geopolitical signalling.

Yet in an era where tariffs, sanctions, and market access are openly deployed as instruments of leverage, such distinctions are increasingly blurred. Capability convergence is misread as political alignment; diversification is interpreted as obligation. The space for genuine strategic autonomy narrows when partners equate technical interoperability with automatic policy convergence.

The Structural Shift: Economic Coercion at Sea

The most profound change in the maritime environment is the rise of economic coercion as a tool of statecraft. Tariffs, sanctions, financial compliance regimes, insurance restrictions, and port-access controls now shape maritime outcomes as decisively as naval deployments.[12] Power at sea increasingly flows through rules, pricing, and risk rather than through presence alone.

For India, the experience of trade friction and tariff pressure—again, particularly during these Trump years—demonstrates that economic interdependence can be weaponised, political partnership does not guarantee insulation, and maritime trade is increasingly subject to strategic pricing. Access to markets, not just access to waters, has become a domain of strategic contestation.[13]

Shipping routes are no longer politically neutral. Energy transport attracts heightened scrutiny. Insurance and reinsurance decisions can determine whether a route is commercially viable at all. Secondary sanctions can affect not only states but private firms, ports, and logistics providers, creating chains of vulnerability that extend deep into domestic economies.[14]

In this context, deeper maritime engagement with Russia must be assessed not only for its strategic symbolism but also for its economic exposure and coercive vulnerability. Diversification is valuable, but only when it genuinely reduces risk rather than redistributes it. A route or partnership that substitutes one set of sanction risks for another does not necessarily enhance resilience.

Connectivity Corridors: Strategy or Symbolism?

Proposals for maritime and multimodal connectivity with Russia—whether through northern corridors, Arctic-adjacent routes, or direct port linkages—are often presented as evidence of a deepening strategic partnership. In principle, such corridors expand options and signal multipolar intent. They can create bargaining leverage and reduce over-reliance on any single maritime highway.

In practice, their value depends on execution. For India, the policy test must rest on clear criteria: cost competitiveness relative to existing routes; reliability and predictability of transit times; availability and pricing of insurance and finance; and port efficiency and regulatory integration.[15] A corridor that looks attractive on maps but fails these tests cannot anchor a strategy.

Absent demonstrable advantages on these metrics, connectivity risks become symbolic rather than strategic. In an era of economic coercion, routes that require sustained sovereign underwriting or attract disproportionate regulatory risk cannot form the backbone of maritime strategy. They may still have tactical or diplomatic utility, but should not be confused with durable economic arteries.

The Indo-Pacific Reality: Power Through Networks

The Indo-Pacific maritime order is not organised around exclusive partnerships or historic alignments. It is shaped by networks of navies, ports, logistics agreements, standards, and trust. Influence depends less on bilateral declarations and more on the density and reliability of these networks.[16]

In this environment, interoperability matters more than episodic presence; logistics access matters more than formal alignment; and standards and data-sharing shape influence as much as platforms. A navy that can plug into multiple coalitions, sustain deployments through diversified access, and share information credibly carries more weight than one anchored primarily in legacy ties.

Russia, despite its importance to India’s maritime past, is not a central organising force in the Indo-Pacific maritime balance. Its naval priorities and resource allocation lie elsewhere. This is not a judgment of intent, but an assessment of capability and focus.[17]

India’s maritime influence in the Indo-Pacific, therefore, rests primarily on its own naval credibility, sustained regional engagement, coalition compatibility, and economic and industrial integration with littoral states. India–Russia maritime cooperation can complement this posture, but it cannot anchor it. To treat it as such would misalign resources with the actual geography of maritime power.

Strategic Autonomy Reinterpreted

India’s concept of strategic autonomy has long emphasised the freedom to make decisions and resistance to external alignment pressures. In the contemporary environment, autonomy must be understood differently. It is no longer about equidistance on a geopolitical spectrum, but about resilience within systems of interdependence.[18]

Autonomy today is the ability to absorb economic and political pressure, switch suppliers and partners without disruption, maintain redundancy in logistics and technology chains, and avoid single points of failure. It rests on the capacity to generate and preserve options, rather than on binary strategic choices.

From this perspective, India–Russia maritime relations retain value precisely because they remain bounded and selective. They enhance choice without demanding exclusivity. They offer additional vectors for capability development, technology access, and diplomatic manoeuvre without determining India’s overall maritime heading.

The risk emerges when legacy partnerships—or new ones—are treated as strategic headings rather than strategic stabilisers. Autonomy erodes when any relationship, however valuable, begins to crowd out choices or lock India into brittle supply chains and political expectations.

Industrial and Capability Considerations

Shipbuilding and maritime industrial cooperation are often cited as future growth areas in India–Russia relations. Here, realism is essential. Industrial cooperation adds strategic value only to the extent that it strengthens design authority, supply-chain resilience, and long-term technological autonomy. Recent Indian industrial engagements with Russian aerospace partners—such as licensed production and engine-manufacturing arrangements—illustrate both opportunity and constraint: they can stabilise sustainment and modestly move the needle on complex manufacturing know-how, but they do not by themselves satisfy India’s quest for frontier technology.

For India, industrial value lies not in assembly or licence production alone, but in the depth of technology transfer, localisation of supply chains, quality assurance, lifecycle support, and export competitiveness.[19] Without these elements, co-production risks reproducing dependency in a new form, merely shifting bottlenecks rather than removing them.

Maritime strategy must therefore align industrial cooperation with long-term indigenisation and resilience goals, rather than platform-centric acquisition logic. The metric of success is not how many hulls can be delivered quickly, but how far each project advances Indian design capability, systems integration, and freedom from coercive leverage in critical components and support.

The Question India Must Balance: What After Trump?

The most difficult strategic question India faces today is not how to manage transactional pressure under Donald Trump, but how to prepare for what comes after him. Trump-style coercion should not be mistaken for an aberration or a policy shift. It was the unvarnished expression of an underlying continuity in Western statecraft, where economic instruments have long been used—often quietly—as tools of strategic influence. The difference lay in tone and transparency, not in intent. ¹

From an Indian perspective, Trump matters less as an individual and more as a signal. A bipartisan consensus in the United States is hardening around industrial protection, the securitisation of supply chains, and the expectation that partners will be judged increasingly by compliance rather than intent. Post‑Trump administrations may soften rhetoric, but the underlying leverage is likely to endure. Waiting for a “return to normal” is therefore not a strategy; the normal has changed. As Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney put it in Davos recently, “we are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition”. Recent US–India trade understandings, under which Trump has announced through social media to reduce its “reciprocal” tariffs in exchange for New Delhi’s reported pledge to halt purchases of Russian oil and buy substantially more US energy, illustrate this logic in practice: economic incentives and penalties are explicitly tied to strategic compliance.

India also faces a subtler danger: over-learning the Trump moment. If New Delhi reacts too sharply to Trump-era pressure and reshapes long-term strategy around short-term personalities, it risks mistaking structural change for episodic disruption. If India curtails strategic autonomy too aggressively, it could signal that pressure works —or treat energy and defence choices as bargaining chips —and create a precedent of inducible compliance—one that future administrations, Republican or Democrat, will inherit.

It is therefore worth stating clearly that the strategic use of defence cooperation as leverage is not unique to Western statecraft, nor to the Trump era. While Western powers have tended to apply such leverage through explicit conditionality—sanctions, export controls, and regulatory pressure—Eastern powers have employed quieter but no less effective methods. China has relied on structural dependence created through supply chains, financing, and dual-use technologies. Russia has exercised leverage through transactional dependencies in sustainment, upgrades, and political signalling. The difference lies less in intent than in method.

For India, the implication is clear: economic and defence coercion are now universal features of great-power competition, and strategic autonomy must be designed to manage pressure from all directions, not selectively interpreted against one set of actors.

Looking beyond any single presidency or single-state dependency, three trends are likely to endure:

- First, economic coercion as policy: tariffs, export controls, sanctions, and compliance regimes have become embedded tools rather than emergency measures, whether raised as penalties or lowered as rewards.

- Second, conditional partnership: interoperability, access, and cooperation will increasingly be paired with expectations—sometimes explicit, often implicit.

- Third, narrative pressure: India will be expected to explain its choices more than before, particularly when those choices diverge from Western preferences—or, as in earlier periods, from Eastern ones.

India’s challenge after Trump, therefore, is to institutionalise a posture that neither defaults to defiance nor slips into deference. It must be able to absorb pressure without escalation, resist coercion without confrontation, and preserve choice without signalling drift. This requires diversification without signalling abandonment, transparency without concession, and consistency across administrations. Above all, it requires strategic patience. Long-term strategic pursuits cannot be subordinated to episodic political pressure; strategic planning must be insulated from short-term shifts in external posture if enduring capability development is to be sustained.

The core balancing question that emerges is stark: can India demonstrate that it is a reliable strategic partner without becoming a predictable one? That balance—between reliability and independence—will define India’s maritime and grand strategy long after Trump, regardless of who occupies the White House or even the Kremlin. It is in this post-Trump context that legacy maritime partnerships, especially with Russia, must be situated: as instruments that expand India’s room for manoeuvre, rather than as tokens to be traded in response to episodic pressure.

Conclusion: Continuity Without Captivity

India–Russia maritime relations remain an important element of India’s strategic inheritance. At critical moments in India’s maritime evolution, they contributed materially to capability development, institutional confidence, and the pursuit of strategic autonomy. That legacy continues to provide ballast in an increasingly complex and contested geopolitical seascape.

What has changed is not the logic that shaped India’s past choices, but the environment in which those choices must now be exercised. Maritime power today is mediated as much through economic systems—regulation, finance, insurance, supply chains, and standards—as through naval force. Pressure is increasingly applied through tariffs, compliance regimes, and market access rather than solely through military means. In this setting, India’s central strategic task is to ensure that legacy partnerships expand its capacity to absorb pressure and preserve choice, rather than narrowing its room for manoeuvre.

Seen in this light, the challenge is no longer about choosing between historical relationships and contemporary alignments. It is about managing continuity without captivity—integrating trusted partnerships into a networked maritime strategy that remains resilient under economic coercion and adaptable across shifting geopolitical contexts. The balance between reliability and independence, rather than alignment or abandonment, will define India’s maritime posture in the years ahead.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that Make in India is often presented as the answer to such complexity. While industrial localisation is undoubtedly a necessary pillar of strategic autonomy, it is at best a partial response. Building platforms at home can mitigate certain supply-chain and sanctions risks, but it does not, by itself, resolve exposure to foreign technologies, standards, finance, insurance, or regulatory leverage. In the maritime domain in particular, resilience depends not only on where platforms are built, but on who controls critical subsystems, data architectures, reinsurance, and access to global logistics and capital.

Make in India, therefore, strengthens autonomy—but it cannot substitute for a broader strategy built on diversified dependencies, networked partnerships, and deliberate economic risk management. It is this larger strategic design—rather than debates framed in terms of alignment or disengagement—that India’s maritime community must now carry forward.

Title Image Courtesy: IMB

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and the Defence Research and Studies. This opinion is written for strategic debate. It is intended to provoke critical thinking, not louder voices.

References

[1] See, for example, Defence Research and Studies (DRaS), India–Russia Maritime Relations: Measuring the Depth of the Partnership, January 2026; and related analyses tracing the evolution of India–Russia naval cooperation from the Cold War period to the present.

[2] Srinath Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), chapters on early post-independence defence planning; R.D. Pradhan, 1965 War: The Inside Story (New Delhi: Atlantic, 2007); and declassified British records on Indian Ocean defence planning in the late 1940s.

[3] Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century, 4th ed. (London: Routledge, 2018), esp. chapters on maritime power beyond naval force; Daniel Yergin, The New Map (New York: Penguin, 2020), sections on energy, trade, and geopolitical leverage.

[4] Christian Bueger, “What Is Maritime Security?” Marine Policy 53 (2015): 159–164; Geoffrey Till, Seapower, chapters on maritime systems and economics.

[5] Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman, Underground Empire: How America Weaponized the World Economy (New York: Henry Holt, 2023), on non-military instruments shaping strategic outcomes.

[6] Rajesh Basrur and Sumitha Narayanan Kutty, India’s National Security: Annual Review (Oxford: Oxford University Press, multiple editions); Indian Navy, Indian Maritime Doctrine (New Delhi: Integrated Headquarters, MoD).

[7] Ministry of Defence (India), annual reports and press releases on induction of P-8I aircraft, MH-60R helicopters, LM2500 propulsion systems, and naval ISR platforms; Indian Navy public briefings and parliamentary replies, 2009–2024.

[8] Milan Vego, Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas (London: Routledge, 2013); US Navy, Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, 2015 and 2020 editions.

[9] Donald Trump administration trade and tariff actions affecting India, 2018–2020; Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), annual National Trade Estimate Reports.

[10] White House, U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy, January 2014; White House, U.S. Conventional Arms Transfer Policy, April 2018; Michael Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2015); Michael Pillsbury, testimony before the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission, Washington, DC, various hearings, 2010–2016.

[11] Government of India, Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, data on crude oil imports, 2022–2024; Ministry of Defence statements on legacy air defence acquisitions and capability gaps.

[12] David Baldwin, Economic Statecraft (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985); Farrell and Newman, Underground Empire; European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), reports on sanctions and economic coercion.

[13] Financial Times, reporting on US–India trade frictions and tariff disputes, 2018–2020; USTR statements on market access and trade compliance.

[14] International Group of P&I Clubs, advisories on sanctions and shipping insurance; Lloyd’s List Intelligence, reports on sanctions-related maritime risk.

[15] World Bank, Logistics Performance Index (latest editions); Asian Development Bank, feasibility studies on multimodal trade corridors; OECD reports on trade facilitation and transport costs.

[16] US Department of Defense, Indo-Pacific Strategy, 2019 and 2022; Quad Joint Statements on maritime security and logistics cooperation.

[17] International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), The Military Balance, sections on Russian naval deployments and priorities.

[18] C. Raja Mohan, Modi’s World: Expanding India’s Sphere of Influence (New Delhi: HarperCollins, 2015); Shyam Saran, How India Sees the World (New Delhi: Juggernaut, 2017).

[19] Ministry of Defence (India), Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP); Comptroller and Auditor General of India, reports on defence production and indigenisation.