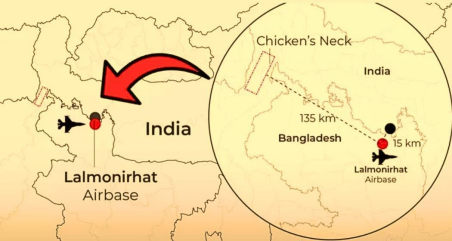

The Siliguri Corridor—colloquially known in Indian strategic discourse as the “Chicken’s Neck”—is one of the most critical and vulnerable terrestrial links in South Asia. It is the narrow land bridge that connects India’s northeastern states (Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura and Sikkim) with the Indian mainland. Bounded by Nepal to the west, Bhutan to the north, Bangladesh to the south, and China’s strategically sensitive Chumbi Valley to the east and northeast, this corridor’s geography situates it at the intersection of multiple geopolitical fault lines. Its strategic significance arises from the fact that any disruption—whether military, political, economic or infrastructural—could sever India’s physical link to its eight northeastern states.

Geographic and Strategic Profile

The Chicken’s Neck stretches for roughly 200 kilometres through North Bengal in the Indian state of West Bengal, with an actual width of about 20–25 kilometres at its narrowest point between Phansidewa and Panitanki, near the borders with Bangladesh and Nepal. This constriction creates a classic bottleneck. Unlike broad expanses of territory that allow for dispersal of forces and logistics, the corridor’s narrowness concentrates India’s infrastructure—its highways, rail lines, and energy and communications networks—into a tightly compressed space. This geometry makes it inherently susceptible to disruption from external military pressure, internal insurgent or destabilising activity, and even natural disasters.

PC: https://thedarjeelingchronicle.com

This vulnerability is compounded by the dense civilian population within and around the corridor, which complicates militarisation without adverse collateral effects and restricts manoeuvre space during large-scale mobilisations. The corridor’s importance goes beyond simple connectivity: it is a linchpin for India’s Act East Policy, economic growth in the Northeast, cross-border trade, regional integration and national cohesion.

Major Strategic Concerns: China and Bangladesh

PC: CivilsDaily

China has a strategic Leverage and the Chumbi Valley. The People’s Republic of China has long viewed the Siliguri Corridor as a potential pressure point against India in the event of a wider conflict. From a purely geometric perspective, if Beijing could threaten or disrupt this narrow corridor, India’s ability to reinforce, resupply or evacuate its northeastern states would be critically impaired. This does not necessarily require a full-scale invasion; simply holding high ground in the eastern Himalayas—including in areas such as the Chumbi Valley tri-junction with Sikkim and Bhutan—allows PLA (People’s Liberation Army) artillery and missile forces to threaten Indian infrastructure and logistics lines pointing towards the corridor. China’s infrastructure build-up around Doklam and its growing presence in Bhutanese and Bangladeshi territory are perceived in New Delhi as part of a broader attempt at strategic encirclement.

For example, China is reported to have assisted Bangladesh in reviving the Lalmonirhat airbase, located just 12–15 kilometres from the Bangladesh–India border and approximately 135 km from the Siliguri Corridor. While officially a civilian facility, its proximity to Indian territory raises strategic alarms—dual-use infrastructure close to the corridor enhances surveillance and potentially provides a staging point for coercive operations or rapid force projection.

PC: News Arena India

More broadly, China’s strengthening of its road, rail and air connectivity across its frontier regions, along with advanced ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) platforms such as satellites and UAVs, means that Indian troop movements and logistics through the corridor are increasingly observable, creating asymmetries in situational awareness that Beijing can exploit.

Bangladesh: Political Flux and Strategic Uncertainties

Historically, India and Bangladesh have shared generally cordial relations, especially after the resolution of key boundary disputes and cooperation on trans-border connectivity agreements. However, the political landscape in Dhaka has seen flux, particularly following the ouster of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in 2025. Reports of renewed engagement between Bangladesh’s interim leadership, Pakistan’s military establishment, and increased Chinese presence in Bangladeshi infrastructure projects have created fresh anxieties in New Delhi about its eastern flank.

While Bangladesh’s military capability is limited compared to India’s, even non-kinetic forms of pressure—such as allowing its territory to be used for surveillance facilities, enabling third-party deployments, or tacitly permitting proxy operations—could indirectly affect the operational security of the Siliguri Corridor. Moreover, geographic proximity means that destabilisation of Bangladesh or spillover effects from internal unrest could lead to large-scale human movement across the border, complicating security management and requiring diversion of Indian resources.

PC: https://www.ejsss.net.in/

Indian domestic political leaders have cautioned Bangladesh against any attempts to influence the strategic balance around the corridor, even asserting that Bangladesh itself has two “chicken necks”—the north Bangladesh corridor (Dakhin Dinajpur to South West Garo Hills) and the Chittagong corridor from South Tripura to the Bay of Bengal—which could be equally vulnerable if not more so. Such statements underscore the mutual sensitivity of narrow land bridges in South Asia’s geopolitics.

The Vulnerability Thesis: Why the Corridor is a Strategic Liability

Analysts characterise the Chicken’s Neck not as an isolated military target but as a multi-domain vulnerability, where conventional military threats intersect with hybrid challenges—logistical chokepoints, economic constraints, social congestion and infrastructure fragility. The narrow geometric profile means that a coordinated disruption— whether kinetic, informational or economic—would create disproportionate dislocation effects.

Infrastructure Fragility and Single Supply Lines

One of the seminal risks for the corridor is its reliance on a limited number of critical infrastructure nodes, notably the single railway line connecting the Northeast with the rest of India and a handful of national highways that snake through the narrow stretch. Damage to these lines—whether by natural events (landslides due to monsoon rains are common in the region) or by hostile sabotage—would halt rail connectivity, severely constraining military and civilian logistics.

Multi-Domain Threats: Cyber, ISR and Electronic Warfare

In the modern strategic environment, vulnerability is not confined to conventional ground manoeuvre. Communications networks— especially fibre optic lines that often run through neighbouring countries like Nepal and Bangladesh—are susceptible to interception or disruption. Cyber and electronic warfare operations that target command and logistics networks could paralyse India’s ability to coordinate responses if the corridor were threatened.

Hybrid Warfare and Proxy Dynamics

Disrupting the corridor does not require open warfare. Strategic signalling through selective proxy operations, fomenting unrest, infiltration via porous borders, trafficking and smuggling—these are all vectors by which an adversary could complicate Indian security postures within the corridor, necessitating resource diversions and creating friction for India’s Eastern Command.

Indian Protective Measures: Hard and Soft Security Postures

Despite these vulnerabilities, India has systematically developed a layered defensive architecture that combines conventional military preparedness, border management, infrastructure strengthening and diplomatic engagement.

Military Posture and Force Deployment. The Indian Army’s Trishakti Corps (33 Corps), headquartered at Sukna near Siliguri, is tasked with overseeing the defence of the corridor. It maintains a high state of readiness through frequent manoeuvres, live-fire exercises with main battle tanks (e.g., T-90s), and interoperability drills in diverse terrains. Complementing this ground focus, the Indian Air Force fields assets such as Rafale and MiG fighter jets from nearby Hashimara Airbase to secure aerial approaches, while long-range strike systems such as the BrahMos supersonic cruise missiles provide offensive deterrence.

India has also augmented its border deployments along the Bangladesh frontier with new garrisons at Bamuni (near Dhubri), Kishanganj and Chopra, enhancing rapid response capabilities and tactical flexibility in countering infiltration and threats emanating from the south.

Advanced Air Defence and ISR Systems

To mitigate aerial and missile threats, India has deployed multiple layers of air defence systems in the eastern theatre. These include the Russian-made S-400 Triumf long-range surface-to-air missile system, indigenous Akash missiles, and DRDO–Israeli jointly developed MRSAM systems. The integrated network creates overlapping coverage, deterring possible incursions and reinforcing strategic depth around the corridor.

Surveillance and ISR capabilities—both aerial and satellite-based— help maintain situational awareness of potential hostile actions near the corridor, providing early warning and targeting data for rapid responses.

Border Security and Internal Stabilisation

The Border Security Force (BSF) has implemented robust border management measures along the India–Bangladesh boundary in the Chicken’s Neck area, including the deployment of high concertina fencing, enhanced patrolling with thermal cameras, night-vision systems and drone surveillance. Such proactive fronts reduce the risk of cross-border infiltration and smuggling that could undermine internal security.

Local police initiatives have also banned unauthorised drone usage to prevent reconnaissance by hostile elements and restricted the sale of military-style fatigues to preclude their misuse for impersonation in subversive actions.

Diplomacy and Regional Engagement

India pursues active diplomatic engagement with Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh to sustain peaceful borders and collaborative security frameworks. Maintaining good relations helps forestall scenarios where external powers might exploit regional fractures to their advantage.

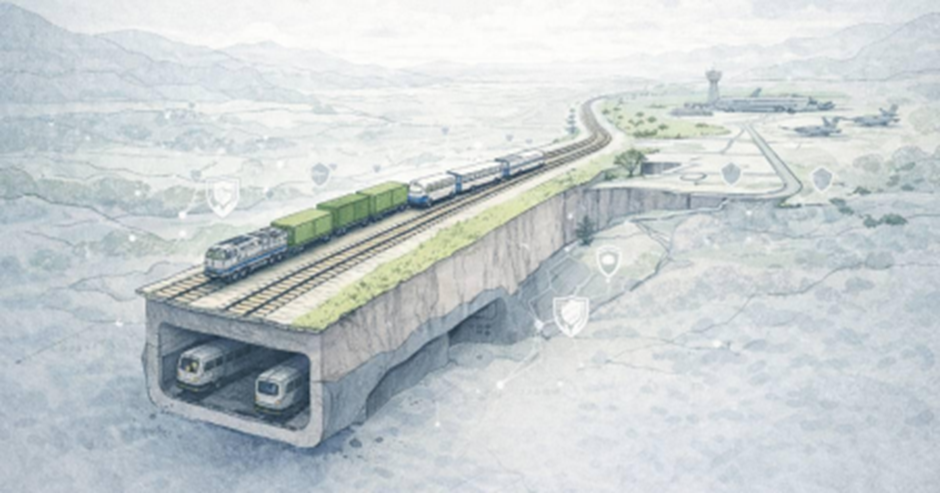

Underground Railway Line: Strategic Logic and Implications

Amidst these protective approaches, one of the most discussed strategic initiatives is the plan to develop an underground railway line through the Chicken’s Neck corridor. According to recent reports, India is preparing to lay a railway link several dozen metres underground between Tin Mile Hat and Rangapani stations near Siliguri. The technical design envisages burying this critical infrastructure at depths of 20–24 metres to protect it from disruption during crises.

PC: Rediff

Rationale Behind Undergrounding

The logic behind undergrounding is straightforward:

Hardening Resilience: Tunnelling the railway reduces vulnerability to artillery, air strikes, sabotage and physical blockade by hostile actors. Underground tunnels cannot be easily damaged by surface bombardment or blocked by blockades without significant engineering effort and time.

Continuity of Supply: In any prolonged crisis or conflict where roads and surface infrastructure might come under attack or obstruction, an underground rail link would ensure continuity of military logistics, evacuation of civilians and movement of supplies to reinforce Northeast India.

Deterrence: The very existence of hardened subterranean logistics infrastructure elevates the cost and complexity of any hostile attempt to sever India’s northern link, adding a layer of deterrence.

Strategic and Technical Challenges

However, the project is not without challenges:

Engineering Complexity and Cost: Constructing a deep underground rail link through the variable geology of North Bengal, prone to high rainfall and landslides, is technically demanding and costly. It requires advanced tunnelling machines, continuous geotechnical monitoring and contingency plans for air-raid protection and ventilation.

Operational Logistics: Even underground, the corridor must accommodate high traffic volumes in peacetime and peak military mobilisation during crises. Integrating this tunnel with surface networks without creating new bottlenecks requires careful planning and phased execution.

Security Integration: The underground rail must be integrated with hardened command and control systems, EMP protection for communication networks, and redundant power supplies—since cutting power alone could disable rail operations irrespective of tunnel protection.

Implications for Regional Security

If successfully implemented, an underground rail link would have multiple implications:

Enhanced Force Mobility: It would significantly improve India’s ability to deploy reinforcements into Assam and other northeastern states rapidly, even under sustained hostilities.

Political Signal: It sends a clear strategic message to potential adversaries that India recognises its vulnerabilities and is willing to invest in structural remedies.

Economic Dividend: Beyond military utility, an underground rail could reduce transit times for civilian connectivity, boost trade and open up ancillary opportunities for freight logistics.

At the same time, infrastructure that is perceived as hardened military logistics can itself become a target for sabotage in hybrid warfare. Thus, its protective value must be coupled with comprehensive defensive plans that include cyber and physical security measures.

Strategic Implications and Future Directions

The vulnerability of the Chicken’s Neck remains a central theme in India’s defence planning for the coming decades. Its narrow geometry and position at the crossroads of regional politics make it both a strategic asset for India’s Act East Policy and a potential pressure point that adversaries could exploit in crisis conditions. The evolving strategic environment—particularly China’s expanding footprint in South Asia and periodic political flux within Bangladesh—continues to shape India’s threat perceptions and force posture around the corridor.

Indian planners are increasingly adopting a multi-domain defence concept that encompasses hard infrastructure protection, layered air and ground defence, surveillance and intelligence, diplomatic engagement with neighbouring states, and the ability to pre-empt or respond swiftly to crises. The addition of hardened subterranean rail infrastructure is part of this holistic approach to strategic resilience.

Looking ahead, India must also continue developing alternative connectivity options, including agreements with Bangladesh to use friendly territory for logistical redundancy, enhancement of air bases closer to the northeast, such as advanced landing grounds, and development of rapid reaction capabilities with pre-positioned stocks and joint exercises to ensure seamless integration during crises. It is also essential to maintain active engagement with Nepal and Bhutan to ensure that their sovereignties and security concerns are harmonised with the defence architecture for the corridor.

Ultimately, strategic geography cannot be altered; however, through a combination of technological innovation, deterrence postures and diplomatic bridging, India can address the inherent vulnerabilities of the Chicken’s Neck while converting its location from an Achilles’ heel into a robust anchor of its eastern defence strategy.

Title Image courtesy: TOI

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and the Defence Research and Studies. This opinion is written for strategic debate. It is intended to provoke critical thinking, not louder voices.