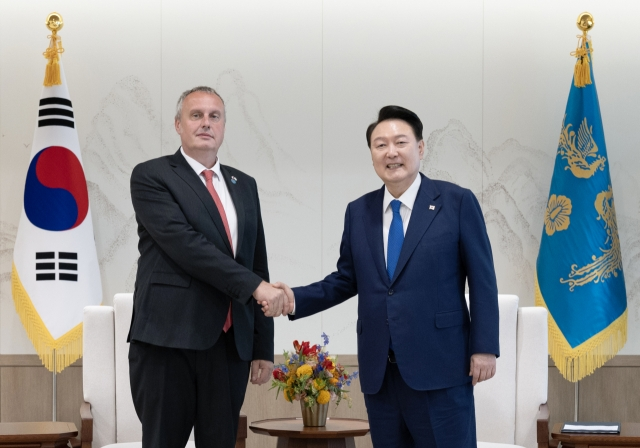

The presidential visit of Yoon Suk Yeol to the Czech Republic in September 2024 holds significance that extends beyond the mere framework of a bilateral diplomatic meeting. At the dawn of an era where global dynamics Nuclear Alliances are being redefined, traditional alliances are being tested, and new technologies shape the contours of economic and military power, this visit emerges as a marker of South Korean ambitions in Europe and beyond. To fully grasp the implications of this visit, it is crucial to delve into the broader context of South Korean foreign policy, which for decades has been dominated by its complex relationships with its immediate neighbours and the world’s great powers. South Korea, often seen as a pivot between East and West, navigates an international environment marked by the rise of China, the constant provocations from North Korea, and the strategic presence of the United States in the Asia-Pacific. In this context, diversifying its diplomatic and economic partnerships becomes not only strategic but necessary. The Czech Republic, a country at the heart of Europe with a rich history and a key geopolitical position within the European Union, represents Seoul much more than just a European partner. It is a potential gateway to a transforming market, an ally in the quest for energy security, and an example of successful democratic and economic transition since the fall of the Soviet bloc. Therefore, this visit is not merely a continuation of diplomatic relations but part of a broader strategy to insert South Korea onto the European chessboard.

It reflects a desire to engage in areas where South Korea excels – notably technology and nuclear energy – while seeking to establish links that could offer a counterbalance or alternatives to the existing dynamics on the Korean Peninsula. Moreover, this diplomatic approach must be examined through the lens of “niche diplomacy,” where South Korea, despite its geopolitical constraints, seeks to assert its influence in specific sectors around the world. Nuclear cooperation, in this context, is not just a matter of commerce or technology; it is deeply political, involving dimensions of security, non-proliferation, and international cooperation in a world where energy resources and their management are central to conflicts and collaborations. This introduction aims to frame Yoon Suk Yeol’s visit not merely as a protocol event but as a chapter in South Korea’s evolution from a regional power to a global actor seeking to influence and adapt to new international realities. The following sections of this article will explore the economic, political, security, and cultural dimensions of this visit, offering an in-depth analysis of what might well be a turning point in South Korea’s international strategy.

South Korea’s Re-Nuclearization Strategy: An Aspiration for Strategic Autonomy

In the contemporary geopolitical arena, South Korea engages in a nuanced and complex process of re-nuclearization, not for nuclear proliferation, but as an expression of its desire to control its geopolitical and energy destiny. This strategy, deeply rooted in the wish to move away from historical dependency on the United States, reflects an aspiration for autonomy that goes beyond the mere framework of national security to touch on the very essence of South Korean sovereignty.

South Korea, since the end of the Korean War, has lived under the American nuclear umbrella, a situation that, while offering protection, has also confined the country to a role of strategic vassalage. This relationship, though beneficial in the context of the Cold War and ongoing tensions with North Korea, has gradually been perceived as a limitation to the full expression of South Korean sovereignty. Re-nuclearization, in this context, is not a whim of power but a calculated step towards energy independence and an autonomous defence posture. South Korea’s civil nuclear program, one of the most advanced in the world, serves as the foundation for this ambition. By mastering the entire nuclear fuel cycle, from uranium extraction to waste treatment, South Korea is not only seeking to diversify its energy sources in the face of climate change challenges and the volatility of energy markets. It also aims to establish a technological and industrial base that could, if necessary, be directed towards military applications, not as a threat, but as a deterrent and an element of independence. This move towards re-nuclearization is also a response to the fluctuating regional context. With the rise of China, uncertainties surrounding American policy in Asia, and the persistent threat from North Korea, Seoul feels the need to assert its position not as a mere pawn in the game of great powers but as an actor capable of defining and defending its interests. The diplomatic aspect of this strategy is equally crucial. By engaging in nuclear partnerships, like the one exemplified by Yoon Suk Yeol’s visit to the Czech Republic, South Korea is not just diversifying its alliances; it positions its nuclear expertise as an asset in its international relations.

South Korea, by mastering the complete nuclear fuel cycle, equips itself with strategic flexibility. This mastery, although strictly civilian and peaceful in its current intent, casts a shadow of capability that could, in a hypothetical future, be converted into military potential if the geopolitical context were to critically deteriorate. This ambiguity, though never explicitly claimed by Seoul, serves as an additional layer in its defence posture, an “unspoken” element that strengthens its position in negotiations and international relations. South Korea’s nuclear diplomacy, therefore, operates on multiple levels: it is both a quest for independence, a foreign policy tool, and a security strategy. Each partnership, each technology transfer, and each reactor project abroad enhances South Korea’s status not merely as a consumer of energy or a protégé under a nuclear umbrella, but as an active and responsible contributor to the global nuclear energy regime.

However, this approach does not come without raising questions and challenges. The international community closely watches how South Korea balances its nuclear development with its non-proliferation obligations. Transparency and cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) are crucial to maintaining trust and preventing nuclear rearmament from being seen as a step towards proliferation. Thus, South Korea finds itself at a crossroads where each decision regarding nuclear and energy policy is weighed not only for its immediate benefits but also for its impact on the country’s image and stature in the world. Nuclear rearmament, in this sense, is as much a technical and economic project as it is an exercise in diplomacy and strategic positioning, reflecting South Korea’s desire to navigate the complexities of the 21st century with a clear vision of its role and global responsibilities.

South Korea and the New Paradigm of Technological Sovereignty

The rearmament of South Korea, when examined from the perspective of technological sovereignty, reveals an even more nuanced aspect of its global strategy. This sovereignty is not limited to the ability to generate energy or mastery over sensitive technology; it extends to the very idea of South Korea as a hub of innovation and an incubator for solutions to future global challenges. In this context, South Korea’s development of nuclear technology should be seen as a cornerstone of a broader policy of technological autonomy. This policy aims to make Seoul not only an exporter of goods and services but also a leader in fields where technology dictates the pace and direction of human progress. Mastery over nuclear technology, with its requirements for research, safety, and waste management, catalyzes advancements in adjacent sectors such as nuclear medicine, materials engineering, and even space, where nuclear propulsion technology might one day become crucial.

This quest for autonomy is also a driver of cultural transformation within South Korea. It encourages a generation of young scientists, engineers, and thinkers to engage in areas critical for national security and development. In doing so, it fosters an innovation culture that sees technology not just as a means to meet current needs but as a tool to shape the future, to anticipate and prepare South Korea for challenges yet to emerge.

The diplomatic dimension of this technological sovereignty is equally significant. By becoming a provider of safe and sustainable nuclear technologies, South Korea does not merely expand its influence; it offers an alternative, a model of nuclear development that advocates cooperation rather than confrontation, and sharing rather than isolation. This model becomes a selling point in its relations with emerging or developing countries, seeking to offer them a path to energy independence without compromising their commitment to non-proliferation. However, the path to this form of sovereignty is paved with internal and external challenges.

The South Korea – Czech Republic Meeting: A Strategic Exchange

In this context of rearmament and the quest for energy autonomy, the meeting between South Korea and the Czech Republic takes on significant importance. This meeting is not just a dialogue between two nations but a crossroads where energy, technological, and diplomatic issues intersect.

Energy Context

The Czech Republic, like many European countries, seeks to diversify its energy sources. Dependence on fossil fuels and the desire to reduce its carbon footprint drive it to explore viable alternatives. South Korean nuclear technology, recognized for its efficiency and safety, therefore becomes a potential partner of choice. For South Korea, this relationship is an opportunity to demonstrate its technological leadership and position its nuclear companies in the European market.

Technological Implications: South Korea, with its mastery over the complete nuclear fuel cycle, offers not only reactors but also expertise in fuel cycle management, nuclear safety, and training. For the Czech Republic, collaborating with Seoul could mean access to cutting-edge technologies, enhancement of its own research and development capabilities, and potential cooperation in adjacent fields like nuclear medicine or information technologies applied to energy.

Diplomatic Aspects

Diplomatically, this meeting could catalyze to strengthen ties between East Asia and Central Europe. By engaging in partnerships with nations like the Czech Republic, South Korea diversifies its alliances beyond its immediate neighbours and the United States, which is strategic in a geopolitical context where influence is also played out in the field of technology and energy. For the Czech Republic, associating with South Korea can also be seen as a way to position itself in global power plays, partially freeing itself from intra-European dynamics or Russian influence.

The Nuclearization of Korea and its Aspirations for More Energy and Security Autonomy:

When “Korea” is mentioned in the context of the Korean Peninsula, it generally refers to South Korea (the Republic of Korea), particularly in discussions about nuclearization and energy autonomy. Here is an exploration of this theme:

Historical and Energy Context

South Korea has actively developed its nuclear sector since the 1970s, initially motivated by the need to reduce its dependency on energy imports following the oil shocks. The country, lacking significant energy resources, saw nuclear power as a path to partial energy autonomy. By 2024, South Korea is one of the countries with the largest number of operational nuclear reactors, providing a substantial portion of its electricity, despite debates over phasing out or maintaining nuclear power through successive administrations.

Desire for Energy Autonomy – Energy Diversification

South Korea has sought to diversify its energy sources. Although nuclear power is a key component, there have been moves towards renewable energies. However, the reopening or continuation of nuclear programs reflects a desire not to abandon an energy source that reduces its dependence on fossil fuel imports.

Technology and Exportation

South Korea has developed its nuclear technology, with companies like KEPCO not only building domestic reactors but also seeking to export this technology. This enhances its status in the global energy sector and contributes to its autonomy through mastery of technology and supply chains.

Security Aspirations – The North Korean Context

The situation with North Korea, which has developed its nuclear arsenal, influences South Korea’s energy and security policy. Although South Korea does not possess nuclear weapons and remains under the American nuclear umbrella, there have been internal debates about the possibility of developing its nuclear capability or hosting American nuclear weapons again as a means of deterrence.

Security Autonomy

This aspiration is not limited to energy but encompasses national security. Mastering the entire nuclear fuel cycle can be seen as a step towards “nuclear deterrence capability,” where the technology and materials necessary for a bomb are within reach, without crossing the line into militarization.

Recent Developments and Public Sentiment

According to posts found on X, there has been a renewed interest in nuclear power in South Korea, especially after political changes and in response to evolving regional threats. This shift reflects both a desire to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to ensure a stable energy source in the face of potential global energy instability.

Conclusion

Nuclearization in South Korea is deeply tied to its aspiration for greater autonomy, not only in terms of energy but also in a broader sense of national security and technological independence. This policy is the result of decades of development and a complex strategy aimed at balancing economic, environmental, and security imperatives in a geopolitically sensitive region.

South Korea, on its path towards greater energy and security autonomy, finds itself at a crossroads where nuclear technology plays a pivotal role. This nation, which once considered phasing out nuclear power, has recently made a U-turn, recognizing in the atom a viable solution not only to meet its growing energy needs but also to assert its independence in a tense geopolitical context. For South Korea, nuclear power has become synonymous with stability and energy security. Recent decisions to extend the life of existing reactors and to build new ones illustrate a desire to maximize the use of this technology. This approach does not fail to evoke the complex prose of modern geopolitics, where every decision, and every technological development, is part of a larger narrative of sovereignty and readiness against international uncertainties. Moreover, South Korea positions itself as a key player in the export of nuclear technologies, seeking to establish partnerships that go beyond mere energy frameworks to touch on global security. This ambition is akin to a prose rich in subtexts, where nuclear energy is not just a matter of megawatts but of diplomacy, cutting-edge technology, and leadership in future energy solutions. The relationship with South Korean nuclear technology can be seen as a form of technical poetry within the prose of national development; it combines practical necessity with a certain elegance in engineering and strategy. Each reactor, each international agreement, adds a line to this prose poem that speaks of resilience, innovation, and a constant search for balance between sustainable development imperatives and national security requirements. Thus, South Korea continues to write its energy and security story, using the pen of nuclear technology to sketch a future where autonomy would not just be a chapter, but the central theme of its modern epic.

South Korea, in its trajectory towards independence and autonomy, stands at a pivotal point in its history where every decision, every partnership, and every strategic direction outlines the contours of its future in a multipolar world. This nation, which has emerged from the shadow of war to become a beacon of technology and economy, now aspires to more pronounced independence from the United States, not in opposition, but in a quest for identity and strengthened sovereignty. In the prose of its foreign and domestic policy, South Korea is slowly writing a new page of its history. This page is woven with threads of technological innovation, civilian nuclear ambition, and diplomacy that seek to balance its relations between the giants that are China and the United States. The relationship with the United States, traditionally seen as a shield against regional instability, is evolving towards a more equitable alliance where South Korea no longer content to be a protégé but a full partner. This desire for independence is expressed in South Korean efforts to diversify its alliances and strengthen its defence, reflecting a collective awareness: in a world where powers balance and counterbalance, autonomy is the true key to security and prosperity. This aspiration is read between the lines of trade agreements, security dialogues, and even in popular culture which conveys the image of a proud Korea capable of defending itself. The desire to partially detach from American influence does not occur in hostility but in a spirit of national maturation. South Korea, through its actions, seems to whisper to history that it is ready to navigate alone, or at least, with maps also drawn by its hand. This transition towards more autonomy is poetic in its complexity, for it is not merely a political act but a narrative of growth, and self-assertion within the concert of nations. Thus, in the prose of contemporary geopolitics, South Korea weaves a narrative where a nation’s independence is not declared with a bang but is cultivated with patience and strategy, hoping to bloom in a world where multipolarity is not just a reality but an opportunity to redefine its role on the world stage.

However, despite all this, nuclear proliferation is hardly a solution for stability. In this nuanced dance of diplomacy and development, South Korea’s approach to nuclear technology serves as both a shield and a spear in its international engagements. While the mastery of nuclear technology provides a strategic depth to its defence capabilities, it also places South Korea under a global microscope, where the balance between peaceful use and potential weaponization is meticulously scrutinized. The international community watches closely, aware that the spread of nuclear capabilities, even if intended for peaceful purposes, could inadvertently contribute to regional tensions or inspire other nations to pursue similar paths.

The narrative of South Korea’s nuclear journey is not solely about energy or security in isolation but reflects a broader quest for a redefined identity in the 21st century’s geopolitical landscape. Here, autonomy means more than self-sufficiency; it signifies the capability to influence, set agendas, and be a protagonist in global narratives rather than a mere participant. South Korea’s strides in nuclear technology echo this sentiment, portraying a nation eager to lead by example in nuclear safety, innovation, and international cooperation.

Yet, the very essence of this nuclear narrative underscores a poignant irony: the pursuit of autonomy through nuclear means could, in theory, lead to an environment less stable than the one it seeks to secure. The proliferation of nuclear technology, even under the banner of energy independence, carries with it the shadow of escalation, where the lines between defence and deterrence blur, and where potential miscalculations could lead to unforeseen consequences.

In crafting its future, South Korea must navigate these waters with caution, ensuring that its quest for autonomy does not inadvertently foster an environment where the stability it seeks becomes even more elusive. The challenge lies not only in mastering nuclear technology but in mastering the art of wielding this power with responsibility, foresight, and an unwavering commitment to global peace. Thus, South Korea’s story is not just about achieving technological prowess or energy independence; it’s about how it writes the next chapters in a world increasingly wary of the double-edged sword that nuclear technology represents. We need to remind, that this diplomatic mutation is a long journey, following political, and government changes.

Title Image Courtesy: https://blog.policy.manchester.ac.uk/

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies