Africa possesses substantial economic potential, boasting significant reserves of global oil (12%) and mineral wealth (over 30%). However, it grapples with various impediments to development encompassing deficient education, healthcare, infrastructure, and governance. The traditional approach of relying on the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been hindered by complicated political dynamics and high levels of corruption. This has led to African countries increasingly seeking financial and investment support from China, especially through BRI and FOCAC initiatives. This paper advocates for a nuanced strategy, where African nations synergistically blend intergovernmental aid and Chinese investments to catalyze sustainable growth and facilitate human development. China’s particular proficiency in infrastructure development aptly aligns with Africa’s imperative requirements, which encompass job creation and the diversification of economic prospects. However, it is vital to exercise discernment and acknowledge that while China’s investments have played a pivotal role in Africa’s development trajectory, they are not a universal panacea. The bedrock of sustainable development rests upon the pillars of education, infrastructure, and proficient governance. To encapsulate, the symbiotic involvement of China in Africa has substantial potential. Nevertheless, this partnership should be a constituent element of a comprehensive strategy that underscores the primacy of sustainable development, economic expansion, and responsible governance. Effective collaboration between African governments and international counterparts assumes paramount importance in unlocking Africa’s latent prowess on the global stage. Through a proactive embrace of their developmental strategy, African nations can pave the way for a brighter future and emerge as pivotal global actors.

Introduction

Africa is essential to world development and advancement in the upcoming century. The continent is home to 54 countries, each with a culture, governmental structures, language, and religion. A vital contributor to the world economy, it also holds 12% of the world’s oil reserves and over 30% of its mineral reserves (UNEP, n.d.). Africa is also the youngest continent globally, with the fastest-growing population, offering immense economic growth and development opportunities. Despite experiencing colonial exploitation, numerous African nations have witnessed significant economic development, including accelerated urbanization and industrialization. However, African nations still face several developmental challenges, including poor access to education and healthcare, high debt levels, inadequate infrastructure, environmental degradation, and governance issues, hindering sustainable and stable economic growth. Addressing these challenges is critical to improving the lives of people on the continent and achieving development goals.

African nations have traditionally sought assistance from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to address their developmental issues. International organizations have utilized aid, including loans and grants for development, as a practical way to encourage and foster development. Nevertheless, difficult political circumstances and inadequate governance lead to ineffective allocation of aid money, further fostering corruption in African countries. Furthermore, aid provision is subject to conditions such as policy changes. However, a new trend has emerged: African governments increasingly seek investment and financial assistance from China. The Chinese government’s strategy for Africa focuses on luring investment to the continent’s countries. In contrast to the World Bank and IMF, which provide loans and grants with conditions, China’s African investment strategy differentiates itself by a “no strings attached” philosophy. African countries have embraced this strategy because it allows them to govern their economic policies and framework without interference from other sources. China has become a trusted bilateral partner for Africa by providing critical financial support for industries, trade, and infrastructure development. The Chinese government has also established the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), an essential platform for promoting international investment and trade.

China’s approach to Africa is more strategic and all-encompassing, with its capacity to concentrate on an agreement that benefits both parties and fosters long-term economic progress. Additionally, it enables China to broaden the scope of its export-driven economy. This paper does not criticize the effectiveness of intergovernmental aid or suggest dependence on China; instead, it urges African countries to take a more proactive approach, beginning with achieving political stability in their governments and striking a balance between intergovernmental aid and development assistance and Chinese aid and investment as each nation acts as a rational player. African nations can promote long-term economic growth and increase their contribution to the global economy. One feature of UN, IMF, and World Bank support is that it emphasizes human development, which can enhance social and human development levels. China’s investment potential may also aid in overcoming an impediment to economic advancement. Both can be used in unison to promote long-term, consistent, and sustainable economic growth and human capacity building. It is essential to hold African governments accountable for meeting their citizens’ basic needs, attracting investment through proactive economic policies, developing a substantial human capital base, and maximizing the potential of their youth populations. If African nations capitalize on the unique opportunity there, they will inevitably become a much more active player in the international world order.

Methodology

Given its potential impact on different African sectors, China’s involvement in Africa has become a subject of great interest. This paper aims to examine China’s outreach to Africa using an experimental design focusing on specific African countries based on China’s investment in the nation. The study will comprise two groups of five countries each, one with limited investment and the other with proactive and significant investment from China. Comparable GDP countries will be included in each group to ensure consistency and avoid analysis inaccuracies. For example, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with significant Chinese investment, is in Group One, while Libya, with a GDP of around $50 billion, is in Group Two. Employing a case study methodology will ensure that the findings and conclusions apply to other African countries. This research will provide a valuable comparative analysis of China’s engagement across various African regions and contexts, focusing on specific opportunities and challenges and anticipated trends and patterns in China’s strategic approach. The chosen countries represent different socioeconomic and geographic regions of Africa, from Botswana, one of Africa’s most developed economies, to landlocked countries such as Zambia, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which have significant natural resources but face challenges such as political unrest and underdevelopment.

This research paper will provide a detailed analysis of five vital chronological sections-

Section 1 will examine how aid and investment differ as economic tools in tackling developmental challenges in African nations. The section will consider the current trends in aid and investments provided to Africa and assess their effectiveness in promoting sustainable development. The paper will also consider the rise of non-traditional donors such as China and their impact on the aid landscape. Additionally, it will include an analysis of the developmental challenges -of bad governance, corruption, and increasing external debt- faced by African nations.

Section 2 will explore the need for a multi-sectoral approach to development in Africa by arguing that a holistic approach is necessary for sustainable development.

Section 3, to create a better understanding, will be a theoretical case study of Zambia’s need for infrastructural development loans and hence will be a comparative study considering two lenders- namely the World Bank and China.

Section 4 will look into Chinese investment in Africa, analysing the motivations behind China’s engagement and the types of investments made. The paper will assess the implications of Chinese investment for Africa’s development and examine the challenges associated with this type of investment.

Finally, in Section 5, the paper will evaluate China as a viable option for bilateral relations with Africa. By examining the benefits and challenges of the China-Africa partnership, the paper aims to provide recommendations for strengthening this relationship.

Aid and Investment in Tackling Africa’s Developmental Challenges: An Overview of Trends in African Countries

Current Trends in Investment

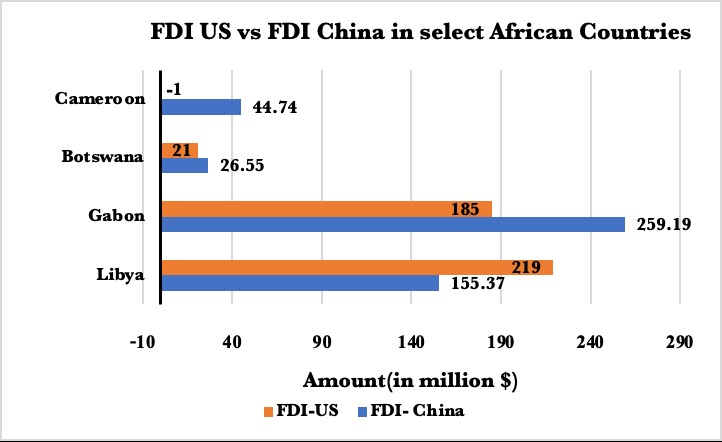

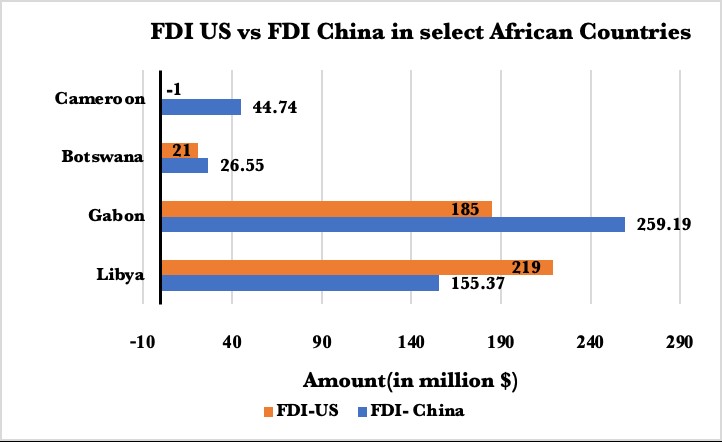

Figure 1 below, which highlights five African nations where Chinese investment has been significantly higher than the US and complements Table 1 with the industries it prioritizes, is a crucial part of the research and provides its framework. The two data help analyse the nature of investment and investment sectors and are in tabulated format. The chart also includes US investment in the five countries where China has made significant investments, making it a comparative study.

In many African nations, foreign direct investment (FDI) is a crucial engine of economic expansion. Figure 1 contrasts the amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI) made by China and the US, mainly African nations, illuminating the rivalry between the two significant investors for influence. The data emphasize the importance of comprehending these investors’ African investment strategies.

Figure 1- Comparing FDI by China and the US in African Countries with significant Chinese investment

Source- By Author, based on various sources[1]

Figure 1 on FDI between Chinese and US investment in African countries with significant Chinese investment highlights China’s dominance in the region’s investment landscape. Table 1, below, provides a more in-depth analysis of the sectors in which China and the US have invested in these countries. Understanding the investment patterns of these major investors is essential to gaining insights into their strategic interests in Africa.

Table 1- Sectors of investment for select African countries with significant Chinese investment

| Country | 2020 GDP (in billion) | HDI (2020) | Sectors of investment (China) | Sectors of investment (USA) |

| DRC | 48.72 | 0.480 | InfrastructureMiningAgriculture ConstructionForestry | OilAgricultureMineralsEnergy |

| Mozambique | 14.03 | 0.456 | InfrastructureEnergyMiningAgricultureManufacturingTourismTelecom | EnergyAgribusinessInfrastructureFisheriesFinancial services tourism |

| Zambia | 18.11 | 0.584 | InfrastructureEnergyMiningConstruction | AgriculturalHospitalityManufacturingEnergyServices industries |

| Uganda | 37.6 | 0.544 | InfrastructureMiningManufacturing and production-communication hospitality | EnergyOilITHealthReal estate |

Source- By Author, based on data from various sources[2]

Table 1 summarizes the speculation examples of China and the US (US) in select African nations with significant Chinese investment. The information shows that China’s interest in these nations is more prominent than that of the US, featuring China’s developing impact in Africa. China’s speculation approach in these nations is multisectoral, with ventures spread across different enterprises. Interestingly, the US venture technique centres more on several businesses, like foundations and energy. This distinction in venture technique is fascinating, and it recommends that China’s methodology is purposeful, pointed toward expanding its speculations and moderating the dangers of putting resources into an isolated area. The information in Table 1 highlights the significance of understanding the venture techniques of significant financial backers like China and the US in African nations, as it gives crucial knowledge into their monetary and international interests.

Even though China’s investment in Africa has grown steadily over the years, some African countries have restricted Chinese investment relative to others. Figure 2 compares the foreign direct investment (FDI) made by China and the US in specific African countries with little Chinese investment.

Figure 2- Comparing FDI by China and the US in African Countries with Limited Chinese Investment

Source- By Author, based on data from various sources[3]

Figure 2, comparing foreign direct investment (FDI) between China and the US in African nations where Chinese investment is relatively low, demonstrates that despite this, China’s FDI still exceeds that of the US. Even though the US has made investments in some of these nations, their totals are insufficient to counteract China’s substantial investment footprint in Africa. This demonstrates China’s continued dominance as a significant investor in the area and emphasizes the significance of comprehending both countries’ investment strategies. Table 2 provides a more in-depth analysis of the sectors in which China and the US have invested in these countries.

Table 2- Sectors of investment for select African countries with minimal Chinese investment

| Country | 2020 GDP (in billions) | HDI (2020) | Sectors of investment (China) | Sectors of investment (USA) |

| Libya | 50.36 | 0.724 | Real estateConstructionRailroadOilTelecomMining | OilEnergy |

| Gabon | 15.31 | 0.703 | Wood(forestry)EnergyConstruction of Special Economic Zones(SEZ)Industrial parksMiningOil and gas | Lumber Oil Mining |

| Botswana | 17.61 | 0.735 | ConstructionMiningManufacturing (textile) AgricultureRetail trade. | EnergyMining |

| Cameroon | 40.77 | 0.563 | OilInfrastructureAgricultureMining ForestryTransportation | AgricultureOil MiningEnergy |

Source- By Author, based on data from various sources[4]

Table 2 lists the industries in which China and the United States have invested in a few African countries where China has made little investment. According to the data, China’s investment strategy in these countries is as sophisticated as America’s. On the other hand, Chinese investment levels are comparable to or even higher in numerous countries than in the US, demonstrating that significant regional Chinese investment cannot be compensated for by US investment in some African countries. It underlines the importance of investigating the underlying causes of these significant investors’ African investment strategies.

Why Aid Falls Short: African Nations Require More Than Hand-outs

Investment and aid are two distinct approaches to promoting economic growth in a country. Aid is when foreign governments or organizations provide financial, technical, or material support to combat poverty or address particular issues. Development aid focuses on steady economic growth through investments in infrastructure, healthcare, and education. Investment can create job opportunities, improve infrastructure, and encourage regional business expansion, contributing to developing sustainable economies and higher living standards in developing countries. Assistance and investment must be balanced to address immediate needs while promoting long-term economic growth. Understanding aid and investment’s various forms and goals is essential for effective economic growth.

Current trends in the types of aid given to African countries focus on the healthcare sector, specifically humanitarian and medical aid. International organizations like the UN have prioritized individual welfare by providing security and humanitarian aid. According to the UN’s 2021 annual country reports, Libya received 171 million USD in aid overall (United Nations, 2022), with most of that money going towards providing short-term relief and improving lives. Sanctions have reduced the value of investments, estimated to cost the Libyan economy $4 billion (Birkett & Sejko, 2022). Table 3 compares the aid and development assistance provided to particular African nations and the donors/creditors who provided it. The table thoroughly overviews the aid types and the sums each donor/creditor allotted. It draws attention to the growing significance of non-traditional donors like China in helping these African nations develop.

Table 3- Aid v. developmental assistance to the countries and donors

| Country | Net ODA | Net humanitarian funding | Humanitarian funding by China | Humanitarian funding by US |

| Zambia | 1,015,870 | 42,292,237 | 487,917 | 6,099,394 |

| DR. Congo | 3,377,360.11 | 1,130,040,751 | 2,291,600 | 570,479,015 |

| Mozambique | 2,547,300.05 | 196,734,642 | 62,301 | 60,750,106 |

| Uganda | 3,082,590.09 | 248,823,007 | 116,600 | 122,533,926 |

| Libya | 295,989.99 | 219,028,185 | 3,602,133 | 35,054,140 |

| Gabon | 53,200 | 10,549,621 | – | 216,000 |

| Botswana | 78,710 | 5,970,784 | – | – |

| Cameroon | 1,399,810.06 | 228,245,522 | 2,192,990 | 83,605,014 |

Source- By Author, based on data from various sources[5]

The need for both humanitarian aid and development assistance for these African nations is emphasised in Table 3 as well. The table demonstrates that the US has been more active in providing humanitarian aid in comparison to China. However, because of the focus on humanitarian aid, developmental aid, investment which could make a significant contribution to sustainable development, has not received the attention it merits. Investment in projects that increase capacity can raise living standards and lessen the need for humanitarian aid. Both forms of support must be given to these nations in order to help them achieve sustainable development.

Challenges to development

- Corruption

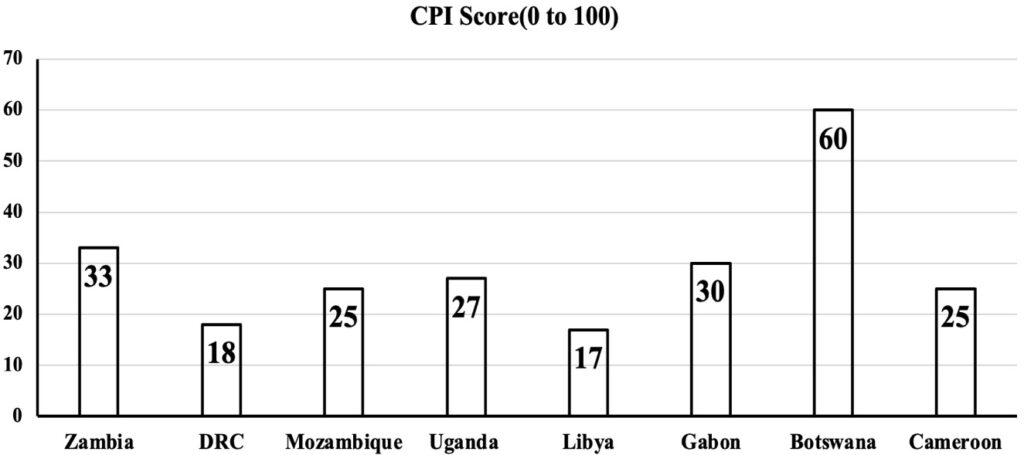

The perception of corruption in various nations is measured using the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), a metric. Corruption is a serious problem that has a negative impact on both the nation’s economic development and the daily lives of its citizens in many African nations. Figure 3 in this context offers information on the level of corruption that exists in select African countries.

Figure 3- Corruption Perception Index score in selected African countries, 2020

Sources- Author, based on data from Transparency International (https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020)

According to Figure 3, the poor rankings of a few African countries in the Corruption Perception Index for 2020 are a sign of the country’s ongoing political unrest and corruption. Despite this, donors continue to provide funds without ensuring their efficient use for the betterment of people’s lives. Multilateral loans have decreased while bilateral loans have increased. Corruption is a prevalent issue regardless of a nation’s level of development or political system. However, in Africa, corruption takes on a unique character shaped by several factors, including the lack of government accountability and transparency. Weak institutional frameworks and limited resources make investigating and prosecuting corrupt officials challenging, while political influence often affects the judiciary. A lack of transparency, accountability, and powerful government institutions can lead to corruption, stifling economic growth and development ( Chakraborti, Lijane, Ndulu, Ramachandran, & Wolgin, 2010). External actors, such as international corporations and foreign governments, also contribute to corruption by taking advantage of weak regulatory frameworks and engaging in practices like tax evasion, illegal resource extraction, and bribery. This alarming pattern creates a vicious cycle in which corrupt leaders in African nations obtain loans that negatively impact the populace, leading to political, economic, and social repercussions that ultimately hurt the most vulnerable members of society.

In Africa, economic instability often pushes individuals to join militias for a better life for themselves and their families (Raleigh, 2016). However, political power struggles have hindered growth in many African countries, leading to a dependence on aid to maintain essential security and support economic expansion. While aid has its benefits, it focuses primarily on healthcare programs and fails to address African nations’ diverse developmental challenges. A multisectoral approach should include investments in the manufacturing, energy, and telecommunications sectors, which aim to promote long-term economic growth and resilience—shifting the economies in the region from solely being dependent on imported goods and services. By promoting African exports, foreign direct investment can increase, allowing African countries to repay debts and maintain control of their industry. Additionally, diversifying economies beyond primary industries like agriculture and mining can increase resilience to global economic shocks. Technical assistance and expertise can also improve human capital and build capacity, leveraging the continent’s expanding youth population (World Bank, 2018). External assistance must address these issues to help African nations become economically stable and fully participate globally.

- Lack of good governance

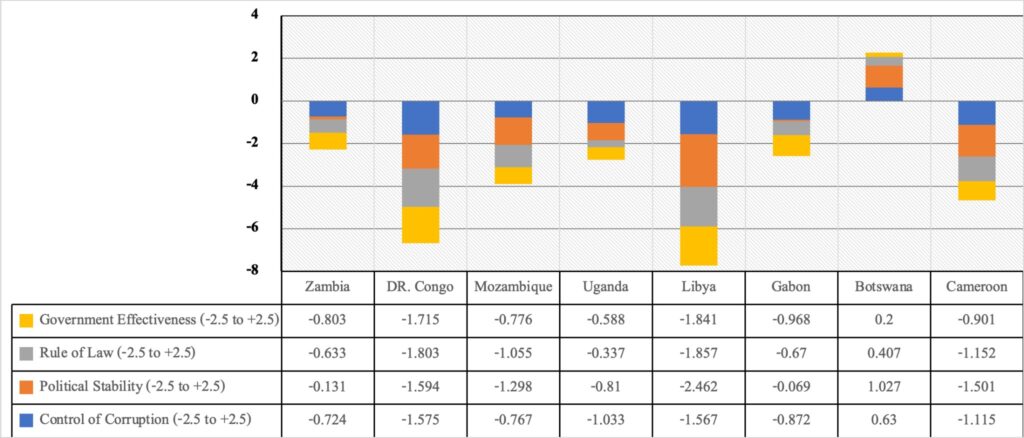

The widespread problems with lousy governance on the continent are the underlying cause of many of the developmental challenges that African nations face. Political corruption and instability are prevalent, with many nations plagued by intra-state conflicts such as civil wars and structural conflicts (Gyimah-Brempong, 2002). In addition, political instability can create an uncertain environment for businesses and deter foreign investment, hindering the development of critical industries (Dalyop, 2018). Furthermore, civil wars and intra-state conflicts can cause population displacement, infrastructure destruction, and economic disruption, exacerbating existing financial problems. Figure 4 depicts how selected African countries ranked in global governance metrics in 2020. The diagram emphasizes the difficulties in leadership and governance that these nations face and the requirement for practical solutions to these problems. It is crucial to comprehend the governance environment in those nations to inform policies and strategies aimed at enhancing African nations’ chances for development.

Figure 4- Governance Indicators Ranking of Selected African Countries, 2020

Sources[6]– Author, based on data from World Bank (https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?Report_Name=WGI-Table&Id=ceea4d8b#)

The poor state of governance in these countries is shown in figure 4 on the Governance Indicators Ranking of Selected African Countries, 2020. It is important to remember that these countries’ weak governance and leadership can have a negative effect on FDI and economic growth. Investment opportunities are lost in countries with bad governance because investors are more likely to steer clear of those markets.

- Increasing External debt

Infrastructure scarcity in many African countries has had a detrimental impact on economic development, limiting access to markets and essential services like education and healthcare. To address this problem, governments often rely on international loans, which leads to a vicious cycle of debt that makes African nations vulnerable to exploitation by transnational corporations and even other states, who then use the nation’s natural resources to pay off their debts (World Bank, 2022). This debt crisis creates an opportunity cost for African countries with limited financial resources, where prioritizing citizens’ security comes at the cost of giving up the opportunity to provide them with education, clean water, and electricity services. Table 4 provides information on the external debt situation of select African countries and the potential effects on their economic stability and growth. It is essential to understand the debt crisis that many African countries are currently facing and the role of significant international creditors to develop effective strategies to overcome this challenge.

Table 4- Selected African countries External debt in 2020

| Country | External debt stocks to exports(%) | External debt stocks to GNI(%) | Debt service to exports(%) |

| Zambia | 310.6 | 151.6 | 22.2 |

| DR. Congo | 57.8 | 17.2 | 2.2 |

| Mozambique | 1,287.7 | 429.7 | 24.3 |

| Uganda | 300.8 | 46.6 | 12.1 |

| Libya | – | – | – |

| Gabon | – | 52.5 | – |

| Botswana | 32.4 | 10.9 | 3.7 |

| Cameroon | 235.2 | 37.0 | 19.2 |

Sources[7]– Author, based on data from World Bank (https://databank.worldbank.org/source/international-debt-statistics)

As shown in Table 4, many African nations with sizable external debts face a significant challenge due to poor debt servicing. Many African countries with sizable external debts struggle with debt servicing, which leads to defaults that damage creditworthiness and limit future borrowing options. High reliance on China may lead to political and financial dependence, limiting countries’ ability to pursue their policies and jeopardizing sovereignty. It is critical to remember that this is not a debt trap in countries where China is the largest lender, such as Zambia, Gabon, and Cameroon, where the governments are responsible and should be aware of the lender (Were, 2018). With over US$3.4 billion in debt relief reserves offered to African countries through 2019 and more than 133 million in debt relief through its G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (Johns Hopkins SAIS, n.d.), China is a critical player, regularly outpacing many financial institutions. African nations must improve their tax collection and management systems to build their financial reserves and infrastructure to foster long-term economic growth and development.

Beyond Aid: Advancing a Multisectoral Approach to Support African Development

The government must limit how far medical assistance can go to spend money to cover the gaps in coverage and ensure the safety of these medical officials. This assistance has driven successful results, significantly strengthening Africa’s resilience to epidemics and disease outbreaks and significantly increasing life expectancy at birth in Africa, even though it remains low. There is also a trend among the UN peacekeepers in Africa, which has witnessed repeated violations by peacekeepers exploiting their powers by being involved in sexual abuse and drug trade. A recent example surfaced in 2021 when the entire Gabonese peacekeeping force deployed in the Central African Republic had to be sent home after repeated reports of sexual abuse by the peacekeepers (United Nations, 2021). The problem with providing only aid to African countries is that more is needed; these countries need a multisectoral strategy.

According to trends, the exploitation of human and natural capital dominates investments with the primary goal of acquiring vital natural resources. Despite the continent’s abundant natural resources, corporations from various foreign countries own the most active mines in African states. They manifest Africa’s “resource curse” with an exploitation of the continent’s substantial natural resources at the expense of the local populace. A multi-sectoral strategy to improving people’s lives should stimulate sector investments that enable profitable growth and ensure that they have access to food and healthcare. Enlisting the support of international organizations such as the World Bank and IMF is conceivable. However, it comes at a cost. These institutions often follow a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to liberalize the economy and promote political democratization, which can adversely affect the local economy (Halper, 2010). As a result, many African countries are taken advantage of by nations worldwide that provide loans at comparable rates but have political and economic sway over the host nation’s economy. In order to achieve sustained economic growth and prosperity, African nations must adopt policies that support the development of domestic industries, uphold human rights, and prioritize citizens’ welfare.

In order to better understand the challenges African countries face in infrastructure development, this section presents a theoretical case study. This comparative case study focuses on Zambia and the potential benefits and drawbacks of obtaining a loan from either the World Bank or China for infrastructural development. This study helps gain a deeper understanding of the complex issues surrounding infrastructure development in African nations and explores possible paths toward more equitable and sustainable economic growth.

Zambia infrastructural development project loan- A Theoretical case study

The infrastructure development project is essential for Zambia’s growth and economic development. The comparison case is a fictitious $1 billion loan. Where to get a loan must be carefully considered. The World Bank’s loan application process takes five years, whereas China’s process takes three months. At the same time, the World Bank’s IDA provides these criteria to low-income countries deemed uncreditworthy – 1.54% fixed interest rates, 10-year grace periods, and 40-year maturities (Morris, Parks, & Gardner, 2020). On the other hand, Chinese loans provide considerable flexibility, with China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) giving extremely generous terms such as 20-year maturities, 10-year grace periods, and 0% interest rates (Morris, Parks, & Gardner, 2020).

China can provide Zambia with benefits like technical assistance and knowledge to help with project execution, which could create jobs and spur economic growth (Calabrese & Tang, 2020). Due to China’s competitive advantage in technology and project costs, this could be disadvantageous for domestic construction companies. Additionally, China’s non-interventionist financial policy gives borrowers more freedom to implement decisions while still abiding by regional laws. The World Bank, in contrast, does not support the development of technical skills or architectural/technical skills. China has previously provided debt restructuring or cancellation to Zambia for debt repayment issues. G20 debt service suspensions from Chinese lenders for Zambia were $110 million (Johns Hopkins SAIS, n.d.).

Discussing the World Bank loan provision would be more beneficial at an individual level because it would lead to more responsible loan management and a focus on improving individual livelihoods, a more micro-level aspect. China may fund the loan because of its non-interventionist policies and focus on macroeconomic growth, but Zambia’s high Corruption Perception Index (CPI) could lead to financial mismanagement. A Chinese loan default could result in control over the project or ownership of natural resources. In contrast, the World Bank offers more flexibility through longer grace and maturity periods. On the other hand, it is more challenging to get a loan from the World Bank because Zambia has low ratings for both debt sustainability and credit ratings. In the near term, Zambia requires immediate development support, which China supplies. Zambia may improve its credit ratings and debt sustainability by collaborating with China. As a result, it will be eligible to get World Bank loans in the future.

As a developing country, Zambia requires funding for infrastructure projects to boost economic growth. While China has been investing in Africa and may be able to provide an infrastructure loan, the World Bank is a more established lender to developing countries and may also provide benefits. Zambia must carefully weigh the benefits and drawbacks of each option. Borrowing from China may provide more favourable loan terms and technology transfers, but it also carries the risk of debt burden and a lack of transparency. The World Bank provides lower-risk, transparent loan terms with stringent conditions and a lengthy approval process. However, some of the necessary policy changes and reforms may be incompatible with Zambia’s development objectives. Furthermore, due to the World Bank’s limited lending resources, Zambia may encounter competition from other nations and organizations when looking for a loan. Zambia’s infrastructure development is vital to the country’s economic growth and development, so it must secure a loan that will enable it to accomplish its long-term goals without accruing excessive debt. Zambia must carefully consider the terms and conditions of any loan it receives as well as the history and reputation of the lender in order to make the best decision for its future.

Chinese Investments in Africa: A Gambit for Export-led Growth

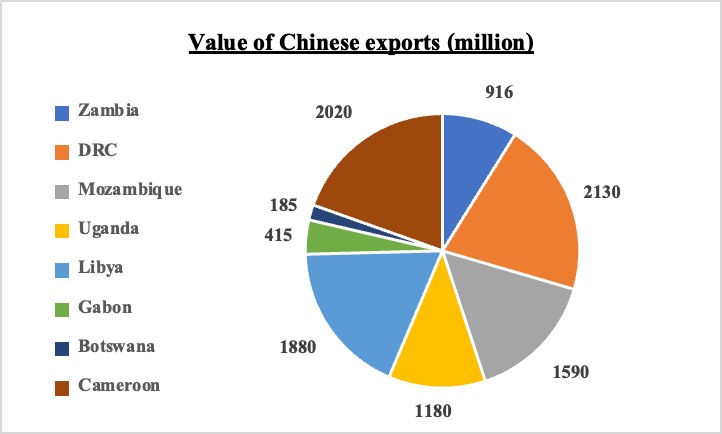

Since the Chinese economy is export-driven and expands rapidly due to trade and economic liberalization, the opportunity to enter the second-most populous continent, Africa, offers a chance to gain access to a sizable market where Chinese goods can become more appealing, ensuring that China can continue to experience export-led double-digit growth. Figure 5 depicts the importance of specific African countries to China’s economy by displaying the significant amount of Chinese exports to these countries. Because of China’s growing market influence in Africa, these exports have been critical in keeping the Chinese economy growing. The graph emphasises the significance of China-Africa economic cooperation.

Figure 5 – China’s Export Value to Selected African Countries in 2020

Sources- Author, based on data from OEC [i](https://oec.world/en)[8]

China shipped goods worth $1.59 billion to Mozambique in 2020, including rubber boots and refined petroleum showing a 21.8% rise from 1995 to 2020 (OEC, n.d.). . China’s objective in Africa is resource-seeking, similar to the investments made by its Western rivals. China, the world’s largest manufacturing economy (Richter, 2021) , constantly acquires resources to meet demand worldwide, but its natural resources are running out. As a result, the nation must look outside its borders for resources.

China’s engagement with Africa has both positive and negative effects. Consumer goods imported from China have competed with and harmed African industries, but in some cases, they have also stimulated healthy competition. Importing specific goods like machinery and technology has helped boost African economic activity. In contrast, mean wages in China have significantly increased, making it harder to profit. The average annual wage rates in China have increased by about 162% in ten years from 2010 to 2020 (Textor, 2021). Nevertheless, on the contrary, investing in the African continent has been a significant challenge for China due to inadequate security and infrastructure, including an erratic public power supply, bad roads, and elevated safety risks.

Essentials such as power, clean water, and education are regularly foregone in African countries with limited financial resources to ensure the populace’s safety. In contrast to its Western competitors, concerned about significant financial losses, China is willing to invest in Africa to acquire underutilized resources for double-digit export-led growth. While speculation supporting could be lost the following day, Chinese interests in Africa ought not to be exclusively considered to be exploitative or a “debt trap.” Even African governments spend much money on defence, which helps stability but takes away investment from education and other necessities. China’s ventures supply the rising worldwide interest in products and advantages from political stability while improving the lives of the general populace. China’s interest in seeing Africa prosper goes beyond a financial burden.

China’s engagement with Africa has included significant infrastructure investment and a willingness to partner with international organizations to lend or renegotiate debt with African states. Although some have denounced Chinese investments as exploitative, recent events show that China’s approach to investing in Africa is more sophisticated than has been depicted in Western media. Contrary to common assumptions, Chinese investments in African countries increasingly focus on the local market. Chinese investors see the continent as a viable market rather than just a hub for low-cost manufacturing (Calabrese & Tang, 2020). As a result of Chinese investment, consumers now have access to more affordable items, which benefits Africa. In contrast to popular belief, China is not utilizing Africa to meet it is expanding need for goods. Table 5 highlights the various development initiatives China has supported and built in specific African nations, including energy production facilities, transportation infrastructure, and other vital sectors. Although China’s investments have raised concerns about debt and transparency, they also provide significant opportunities for African states to advance their development objectives and improve the quality of life for their citizens. The table below summarises some of China’s most significant construction undertakings in Africa.

Table 5- Chinese-Constructed Development Projects in Select African Countries.

| Country | Name and type of project | Assigned company |

| Zambia | Kafue Gorge Lower Hydropower Station | PowerChina |

| DRC | Busanga Hydropower Station in Kinshasa | China Railway Resources Group |

| Mozambique | Maputo ring road | China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) |

| Uganda | Kampala–Entebbe Expressway | China Communication Construction Company |

| Libya | 20,000 housing units | China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC) |

| Gabon | Grand Poubara hydroelectric plant | PowerChina |

| Botswana | Coal-fired power station Morupule B | China National Electric Engineering Corporation (CNEEC) |

| Cameroon | Kribi port | China Harbour Engineering Company Ltd (CHEC) |

Source- By Author based on data from various sources[9]

Infrastructure development, including roads, railroads, and ports, is crucial for growing Africa’s economy. The Chinese government’s investment in these infrastructure initiatives demonstrates, through Table 5, their dedication to aiding the development efforts of African countries. This assistance has improved trade relations between the two nations and created employment opportunities, further strengthening ties between China and Africa. Furthermore, these infrastructure initiatives have improved trade relations between African countries by opening doors to other countries and markets.

China in Africa: Examining a Mutually Beneficial Partnership for

Economic Growth and Development

For prosperity, China and Africa must work together, and China’s expertise in attaining double-digit economic growth—China’s investment in vital infrastructure to support economic development—is crucial. China’s “going global” policy in the 1990s exhorted companies to grow internationally and discover new markets (Zeng, 2015). China’s accomplishments in Special Economic Zones and its export-led growth strategy are examples of its prowess. China has pursued comparable objectives in Africa through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), building and investing in infrastructure projects in congested transportation corridors and building ports and roads with the cooperation of private businesses. The SEZs allowed China to adopt a market-oriented growth model. Chinese businesses investing in Africa have high localization rates, creating numerous job opportunities for African workers, primarily in low- and semi-skilled positions (Calabrese & Tang, 2020).

China’s way of dealing with reciprocal relations with African countries offers a practical option in contrast to customary Western connections attached to government and expansionism. African countries trying to broaden their economies and exchange accomplices benefit from China’s non-interventionist monetary strategy. The rejection by Situmbeko Musokotwane, Zambia’s minister of finance, of China’s proposal for the IMF to restructure the country’s debt highlights this advantage, as “what we are looking for is urgent solutions” (Cotterill, 2023). Chinese investments also provide greater policy latitude for African governments to implement necessary reforms, strengthening their economies. Because it transfers funds quickly and allows governments to implement reforms, China may have more influence over the IMF or the World Bank. Given the beneficiary country’s requirements, China will help out Western establishments, and its interests in Africa will give huge benefits.

China has emerged as a promising bilateral partner for African nations due to its capacity to provide financial assistance and act as a model. Despite China’s interest in natural resources, the country has also made substantial investments in infrastructure to alleviate African nations’ bottlenecks. This speculation has been more far-reaching in Africa, unlike Western countries like the US, covering regions like agribusiness, bringing about expanded crop yield. This partnership is mutually beneficial by allowing African nations to export goods and ensure food security. China is broadening its ventures, zeroing in on massive infrastructural projects that facilitate trade and enhance economic growth in Africa, making it more resilient to global economic shocks.

International corporations, including those from China, are taking advantage of Africa’s young population, abundant resources, and vast arable land. Cooperation with China should not rise to reliance, as it is a well-established fact in international relations that countries pursue their national interests (Gilpin, 2021). The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) prioritizes South-South cooperation over Western counterparts and represents China’s African interest (Diop, 2015). While reliance on China is unsustainable, the development of African countries without Chinese aid and investment is also implausible. On the other hand, the World Bank and IMF are important international financial institutions that African nations should not overlook. Through strategic soft power diplomacy, African nations could benefit from a combination of support from China and international organizations, ensuring the security of natural resources and a dependable long-term market.

Although China’s investment in Africa has contributed to its development, it is not an all-encompassing solution. By investing in education, infrastructure, and other initiatives, African nations must place sustainable development first, fostering an environment for business that is open and accountable. In order to encourage economic development and growth, the continent must be proactive and appropriately allocate aid and investment funds. African governments and international partners must work together to address these issues and make progress. African nations have the potential to develop a prosperous and equitable continent for all by taking responsibility for their development.

Title image: Brookings Institution

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies

References

UNEP. (n.d.). Our work in Africa. Retrieved from United Nations Environment Programme: https://www.unep.org/regions/africa/our-work-africa

Gyimah-Brempong, K. (2002). Corruption, economic growth, and income inequality in Africa. Economics of Governance, 3(3), 183-209.

Chakraborti, L., Lijane, L., Ndulu, B., Ramachandran, V., & Wolgin, J. (2010). Challenges of African growth: opportunities, constraints, and strategic directions. World Bank Group. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Dalyop, G. T. (2018). Political instability and economic growth in Africa. International Journal of Economic Policy Studies, 13, 217–257.

World Bank. (2022, December 6). Debt-Service Payments Put Biggest Squeeze on Poor Countries Since 2000. Retrieved from The World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/12/06/debt-service-payments-put-biggest-squeeze-on-poor-countries-since-2000

Were, A. (2018, August ). Debt Trap? Chinese loans and Africa’s development options. Johannesburg: South African Institute of International Affairs. Retrieved from South African Institute of International Affairs: https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Policy-Insights-66.pdf

Ghanem, H. (2018, September 6). Youth Key to Strengthening Africa’s Future. Retrieved from The World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2018/09/06/youth-key-to-strengthening-africas-future

Raleigh, C. (2016). Pragmatic and Promiscuous: Explaining the Rise of Competitive Political Militias across Africa. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 60(2), 283–310.

Birkett , D., & Sejko, D. (2022, February 8). Challenging UN Security Council- and International Criminal Court-Requested Asset Freezes in Domestic Courts: Views from the United Kingdom and Italy. Israel Law Review, 55(2), 107 – 126.

United Nations. (2021, September 15). UN sends Gabon peacekeepers home from Central African Republic, following abuse allegations. Retrieved from UN News: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1100032

Halper, S. (2010). The Beijing Consensus. New York: Basic Books.

Textor, C. (2021, August). Average annual wages in China from 2010 to 2020 (in yuan). Retrieved from Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/743522/china-average-yearly-wages/

Calabrese, L., & Tang, X. (2020). Africa’s economic transformation: the role of Chinese investment. DFID-ESRC Growth Research Programme (DEGRP).

Zeng, D. (2015). Global Experiences with Special Economic Zones: Focus on China and Africa. World Bank Group.

Cotterill, J. (2023, February 13). Zambian finance minister criticises creditor delays in debt restructuring. Retrieved from Financial Times: https://www.ft.com/content/b136a36b-5822-4647-8efe-67fc18b00ea3

Morris, S., Parks, B., & Gardner, A. (2020). Chinese and World Bank Lending Terms: A Systematic Comparison Across 157 Countries and 15 Years. Washington DC: Center for Global Development. Retrieved from Center for Global Development: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/chinese-and-world-bank-lending-terms-systematic-comparison.pdf

Johns Hopkins SAIS. (n.d.). Global Debt Relief Dashboard. Retrieved from China Africa Research Initiative: http://www.sais-cari.org/debt-relief

Gilpin, S. I. (2021). China, Africa and the International Aid System: A Challenge to (the Norms Underpinning) the Neoliberal World Order? Journal of Asian and African Studies, 0(0), 1-21.

Diop, M. (2015, January 13). Lessons for Africa from China’s Growth. Beijing: World Bank.

CEIC. (n.d.). China Foreign Direct Investment: Capital Utilized: by Country. Retrieved from CEIC data: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/china/foreign-direct-investment-capital-utilized-by-country?page=2

BEA. (n.d.). BEA International Trade and Investment Country Facts. Retrieved from Bureau of Economic Analysis: https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/

World Bank. (n.d.). World Development Indicators. Retrieved from World Bank DataBank: https://databank.worldbank.org/Human-development-index/id/363d401b

U.S. DoS . (n.d.). 2020 Investment Climate Statements: Libya. Retrieved from U.S. Department of State: https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-investment-climate-statements/libya/

Junbo , J., & Méndez, A. (2015). Change and Continuity in Chinese Foreign Policy: China’s Engagement in the Libyan Civil War as a Case Study. London School of Economics, Global South Unit. London: LSE GLOBAL SOUTH UNIT.

Alves, A. C. (2017). China and Gabon: A Growing Resource Partnership. Johannesburg: The South African Institute of International Affairs.

Institute of Developing Economies Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). (n.d.). China in Africa. Retrieved from Institute of Developing Economies: https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Data/Africa_file/Manualreport/cia_10.html

UNOCHA. (n.d.). Humanitarian aid contributions. Retrieved from Financial Tracking Services- UNOCHA: https://fts.unocha.org

World Bank. (n.d.). Net official development assistance received (current US$) . Retrieved from World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.ODA.ODAT.CD?end=2004&locations=LY-GA-BW-ZM-MZ-CD-UG-CM&start=2004&view=bar

Transparency International. (n.d.). Corruption Perceptions Index. Retrieved from Transparency International: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020

World Bank. (n.d.). World Governance Indicators Table. Retrieved from World Bank Database: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?Report_Name=WGI-Table&Id=ceea4d8b

World Bank. (n.d.). International Debt Statistics. Retrieved from World Bank DataBank: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/international-debt-statistics

Hydro Review. (n.d.). Zambia commissions first unit of 750-MW Kafue Gorge Lower hydropower station. Retrieved from Hydro Review: https://www.hydroreview.com/hydro-industry-news/new-development/zambia-commissions-first-unit-of-750-mw-kafue-gorge-lower-hydropower-station/

Government of Uganda. (n.d.). Kampala-Entebbe Expressway. Retrieved from Ministry of Works and Transport- Uganda: https://www.works.go.ug/index.php/component/k2/item/25-kampala-entebbe-expressway

China State Construction Overseas Development So. Ltd. . (n.d.). Performance. Retrieved from CSCECOS: https://www.cscecos.com/page.aspx?node=63

Hydro Review. (n.d.). Gabon’s 160-MW Grand Poubara hydroelectric plant enters full operation. Retrieved from Hydro Review: https://www.hydroreview.com/world-regions/africa/gabon-s-160-mw-grand-poubara-enters-full-operation/

Aid Data. (n.d.). Project ID: 40. Retrieved from China Aid Data: https://china.aiddata.org/projects/40/

Government of China. (n.d.). Kribi Deepwater Port Helps Cameroon Take Off. Retrieved from Ministry of Commerce- China: http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/beltandroad/cm/enindex.shtml

OEC. (n.d.). Trade Data. Retrieved from Observatory of Economic Complexity: https://oec.world/en

Richter, F. (2021, May 4). China Is the World’s Manufacturing Superpower. Retrieved from Statista: https://www.statista.com/chart/20858/top-10-countries-by-share-of-global-manufacturing-output/

China Daily. (2021, August 12). Chinese-built hydropower station in Zambia turns on 1st generator. Retrieved from China Daily: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202108/12/WS61149015a310efa1bd6685db.html

United Nations. (2022). UN Country Team in Libya: 2021 Annual Results Report. UNCT Libya. Retrieved from UN.

World Bank. (2018, September 6). Youth Key to Strengthening Africa’s Future. Retrieved from The World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2018/09/06/youth-key-to-strengthening-africas-future

The Global Economy. (n.d.). Human development – Country rankings. Retrieved from The Global Economy: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/human_development/

World Bank. (n.d.). GDP (current US$) – Congo, Dem. Rep., Zambia, Mozambique, Uganda, Libya, Gabon, Botswana, Cameroon. Retrieved from World Bank Data: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?end=2020&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014

Beseka, M. (2019, March). The Dragon in the River of Shrimp: The Reality and Perception of Chinese Investment in Cameroon. Retrieved from The Yale Review of International Studies: http://yris.yira.org/comments/3012

Gu, X., Dinkelbach , C., Heidbrink, C., Huang, Y., Ke, X., Mayer, M., & Ohnesorge, H. W. (2022, June). China’s Engagement in Africa: Activities, Effects and Trends. Retrieved from University of Bonn: https://www.cgs-bonn.de/cms/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/CGS-China_Africa_Study-2022.pdf

Jansson, J. (2009). Patterns of Chinese Investment, Aid and Trade in Central Africa (Cameroon, the DRC and Gabon). University of Stellenbosch, Centre for Chinese Studies. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch.

[1] For Figure 1. For more data/ details see-

CEIC (https://www.ceicdata.com/en/china/foreign-direct-investment-capital-utilized-by-country?page=2 )

BEA( https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/)

BEA(https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.html#408)

BEA(https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.html#427)

BEA(https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.html#448)

BEA(https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.html#446)

[2] For Table 1 details and data see below-

World Bank(https://databank.worldbank.org/Human-development-index/id/363d401b) and World Bank(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?end=2020&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014)

LSE(http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64375/1/LSE_Working_Paper_05_15%20(Junbo%20%20Mendez).pdf)

SAIIA(https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/chap_rep_04_alves_200805.pdf)

IDE(https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Data/Africa_file/Manualreport/cia_10.html)

The Global Economy(https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/human_development/)

[3] In Figure 2. For details/ data see-

CEIC (https://www.ceicdata.com/en/china/foreign-direct-investment-capital-utilized-by-country?page=2 )

BEA( https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/)

BEA(https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.html#404)

BEA(https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.html#402)

BEA(https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.html#413)

BEA( https://apps.bea.gov/international/factsheet/factsheet.html#421)

[4] For Table 2, details and data see below-

World Bank (https://databank.worldbank.org/Human-development-index/id/363d401b)

World Bank( https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?end=2020&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014)

US DoS (https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-investment-climate-statements/libya/)

LSE(http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64375/1/LSE_Working_Paper_05_15%20(Junbo%20%20Mendez).pdf)

SAIIA(https://saiia.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/chap_rep_04_alves_200805.pdf)

IDE(https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Data/Africa_file/Manualreport/cia_10.html)

The Global Economy(https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/human_development/)

[5] For Table 3 details/ data see-

OCHA( https://fts.unocha.org )

WorldBank(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.ODA.ODAT.CD?end=2004&locations=LY-GA-BW-ZM-MZ-CD-UG-CM&start=2004&view=bar)

OCHA(https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/937/donors)

OCHA(https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/919/donors?boundary=incoming)

OCHA(https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/931/donors)

OCHA(https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/927/donors)

[6] In Figure 4. For details/data see below-

World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GE.EST?end=2021&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014)

World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/RL.EST?end=2021&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014)

World Bank( https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PV.EST?end=2021&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014)

World Bank(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/CC.EST?end=2021&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014)

[7] For Table 4. For details/ data see-

World Bank(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.DOD.DECT.GN.ZS?end=2021&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014)

World Bank(https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.TDS.DECT.EX.ZS?end=2021&locations=CD-ZM-MZ-UG-LY-GA-BW-CM&start=2014)

[8] Figure 5.For details/ data see

OEC(https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/zmb?dynamicBilateralTradeSelector=year2020)

OEC(https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/cod?dynamicBilateralTradeSelector=year2020&depthSelector=HS2Depth)

OEC(https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/moz?dynamicBilateralTradeSelector=year2020)

OEC(https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/uga?dynamicBilateralTradeSelector=year2020)

OEC(https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/lby?dynamicBilateralTradeSelector=year2020)

OEC(https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/lby?dynamicBilateralTradeSelector=year2020)

OEC(https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/bwa?dynamicBilateralTradeSelector=year2020)

[9] For Table 5 details/data see-

Hydro Review (www.hydroreview.com/hydro-industry-news/zambia-commissions-first-unit-of-750-mw-kafue-gorge-lower-hydropower-station/.)

China Railway Group Ltd(www.crecg.com/english/2691/2743/10182171/index.html.0)

Government of Uganda; (www.works.go.ug/index.php/component/k2/item/25-kampala-entebbe-expressway.)

CSCEOS(https://www.cscecos.com/page.aspx?node=63)

HydroReview(https://www.hydroreview.com/world-regions/gabon-s-160-mw-grand-poubara-enters-full-operation/)

AID DATA(https://china.aiddata.org/projects/40/)

MOFCOM-CN (http://www.mofcom.gov.cn/article/beltandroad/cm/enindex.shtml)

China Daily( https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202108/12/WS61149015a310efa1bd6685db.html)