This study examines the potential for enhancing tribal tourism in India by drawing insights from Chile’s indigenous tourism model. Despite India’s rich tribal diversity and cultural heritage, tribal tourism remains underdeveloped and marginalised in mainstream tourism narratives. In contrast, Chile has implemented successful indigenous tourism initiatives that prioritise community participation, cultural preservation, and sustainable practices. Using a comparative analytical approach, this study explores how Chile’s strategies, including legal recognition of indigenous rights, government-supported tourism programs, and public-private partnerships, can inform frameworks in India. The research identifies critical challenges such as land rights disputes, administrative neglect, over-commercialisation, and risks to cultural identity posed by unsustainable tourism development in tribal regions. Drawing on the findings, the study proposes recommendations for inclusive governance, structured capacity-building for indigenous communities, clear regulatory frameworks, and sustainable tourism models that empower tribal communities as custodians of their cultural and natural heritage. The study concludes that legal recognition of tribal land rights and administrative autonomy over traditional territories is essential for achieving culturally sensitive, equitable, and sustainable tribal tourism development in India.

Introduction

As a unique kind of travel, tribal tourism (also referred to as indigenous tourism or ethno-tourism) allows visitors to fully immerse themselves in the particular customs, cultures, and daily routines of indigenous people (Buultjens & Gale, 2013).

In India, the Union Ministry of Tourism, the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs and various respective state institutions, along with the private sector, are providing vital impetus for the growth of tribal tourism, which not only provides them with livelihood, but also facilitates their communication with broader society. However, there exist multiple problems like those mentioned in the cases below, which jeopardise the industry and derail its path toward sustainable development.

India’s offshore islands, the Andaman and Nicobar constitute an important biodiversity hotspot supported by a range of marine and terrestrial biota. These islands are home to some of the world’s last remaining tribes — the Great Andamanese, Sentinelese, Onge, Jarawa, and Shom Pen — who strive to preserve their traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyles amid the pressures of globalisation (Singh, 2006). A report warns that increasing contact through tourism may make the native tribals more vulnerable to diseases (Choubey, 2013). For example, the Jarawa tribe was affected by measles in the 1990s (Kumar, 1999). The arrival of tourists poses an imminent and potentially life-threatening risk to the tribes. Similarly, the tourism sector faced criticism in 2013 following the release of videos showing Jarawa women performing for tourists under exploitative circumstances (Agoramoorthy & Sivaperuman, 2014).

The Sentinelese is one of the six aboriginal tribal communities of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. They live on the North Sentinel Island of the Andaman group of Islands. Perhaps, they are the only truly isolated hunter-gatherers in the world today. Till now, the Sentinelese have maintained their independent existence, repelling all attempts to engage with and contact them. They remained steadfast in opposition to all the efforts of the colonial and post-colonial administration to contain them with the might of their bows and arrows (Sasikumar, 2018). This highlights the strict boundaries established by the Government of India to protect the people of North Sentinel Island. Developments due to tourism can have a disastrous impact on such tribes who are not accustomed to the globalised era of the world. In certain areas, between the pulse of progress and the soul of tradition, a line must be drawn—gently, but unshakably.

In 2018, Mazumdar (TNIE) reported that the Hornbill Festival in Nagaland was negatively impacted by poor infrastructure, including inadequate roads, and exploitative practices such as arbitrary price hikes by hotels and cab drivers. These issues led to dissatisfaction among tourists and highlighted challenges in service quality and regulation within tribal tourism circuits. Vulnerability to diseases, cultural exploitation, loss of autonomy, negative impact on traditional lifestyles, exploitation of resources and unsustainable growth are some of the challenges faced by the tribal tourism sector in India.

On the other hand, Chile is ranked in the top 10 in Latin America and the Caribbean in greenfield FDI investment announcements in tourism. In addition, the country focuses on improving key enablers in the development of the sector through the Special Infrastructure Plan of the Ministry of Public Works to support ‘Sustainable Tourism to 2030’, with projects worth USD 4,188 million until 2026. (World Tourism Organisation, n.d.)

It has stepped onto the path of empowering its indigenous communities through the involvement of the community itself. Previously, their effort in promoting a place called ‘Easter Island’ though succeeded, it destroyed the place’s ecosystem before the Rapa Nui people got back their control over the region and implemented various safeguards for the sustainability of the industry. Moreover, a low tax regime and support for tribal involved tourism has reduced the differences and increased the connection between the tribes and the state.

This paper investigates tribal tourism in India and indigenous tourism in Chile, and provides a comparative analysis of potential solutions that can be implemented in India to enhance tribal tourism.

Literature Review

According to the Census of 2011, the total population of Scheduled Tribes (STs) in India was 10,42,81,034, making up 8.6% of the country’s total population. However, India’s tribal communities are extremely diverse and heterogeneous, differing widely in languages spoken, population size, and livelihoods. Reflecting this diversity, the Government of India’s Draft National Tribal Policy (2006) listed 698 Scheduled Tribes, while the Census of 2011 increased the figure to 705 (Ministry of Tribal Affairs, GoI, 2014).

In terms of demographic distribution, the Himalayan Region accounts for 2.03% of the ST population in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Uttar Pradesh. The Northeastern Region has 12.41% in states like Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, Meghalaya, and Assam. The largest proportion is found in the Central-East Indian Region, with 52.51% in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and West Bengal. The Western Region follows with 27.64%, while the Southern Region contributes 5.31% from Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. Lastly, only 0.11% of STs live in the Island Region of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep (Census of India, 2011).

India is endowed with a rich diversity of indigenous communities spread across its vast landscape, providing a strong foundation for the development of tribal tourism. More than 152 districts in India have a tribal population of more than 25%. States like Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland and the Union territory Lakshadweep have a percentage of Scheduled Tribes (ST) to their whole population above 50% (Source: Census of India, 2011).

Research Questions:

This study seeks to address the following research questions:

- What is the contemporary state of tribal tourism in India, and what are its major challenges and limitations?

- How can insights from Chile’s indigenous tourism be applied to enhance sustainable tribal tourism initiatives in India?

Research Methodology

This research adopts a qualitative comparative analysis approach based on secondary data sources. Key data were gathered through an extensive review of existing academic literature, government publications, policy documents, and case studies related to tribal tourism in India and Chile.

Indian Government Initiatives

The Indian government’s Ministry of Tourism introduced the Swadesh Darshan Scheme in 2015 with the goal of creating destination hubs that are sustainable and socially responsible. Thus far, the scheme has seen 76 projects approved by the Ministry. The redesigned program, called Swadesh Darshan 2.0, aims to achieve Aatmanirbhar Bharat by utilising India’s rich tourism potential under the motto Vocal for Local. To develop sustainable and responsible tourism destinations—including infrastructure, tourism-related services, human capital development, destination management, and promotion, supported by institutional and policy reforms—Swadesh Darshan 2.0 represents a generational shift rather than a gradual improvement (Bandhu, 2024).

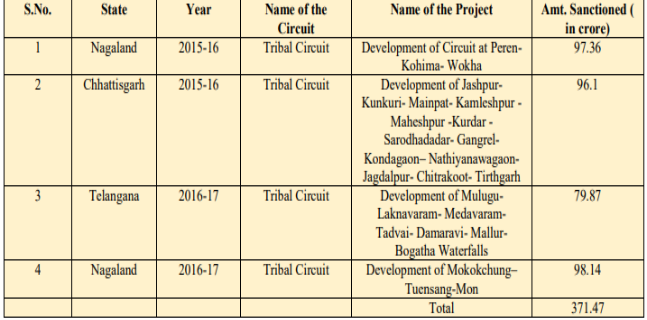

Under the present plan, the government aims to develop ethical and sustainable tourism destinations by adopting a Destination Centric Approach. In this scheme, the government is also working to develop tribal circuits to promote tribal tourism in the country. It is a relatively new form of tourism, so initially, only three states have been selected for tribal circuit development, as shown in the map and table below (Bandhu, 2024).

Table: Projects under the Swadesh Darshan scheme to promote and assist tribal tourism

(Source: Ministry of Tourism, Government of India. (n.d.). Year-wise details of projects sanctioned by the ministry under the tribal circuit/theme of Swadesh Darshan. Data.gov.in.)

The Indian government has been actively promoting tribal tourism through initiatives such as the Swadesh Darshan Scheme (2015) and its upgraded version, Swadesh Darshan 2.0. These programs aim to foster sustainable and responsible tourism by enhancing infrastructure, services, and tourism circuits. Notably, tribal circuits have been identified to boost tourism in areas rich in indigenous culture.

So far, only three states — Nagaland, Chhattisgarh, and Telangana — have been selected for tribal tourism projects under this scheme. It is noteworthy that other states with significant tribal populations, like Meghalaya, have not yet been included, which may limit the scheme’s overall impact. While it’s good that the government is developing tribal tourism, these initiatives should carefully respect the cultural traditions and environments of tribal communities to avoid exploitation or cultural erosion.

Prospects of Indigenous Tourism in Chile

Despite steady increases since the 1990s, Chile’s Indigenous population has experienced no major changes since the 2017 census. At that time, 2,185,792 people self-identified as Indigenous, equivalent to 12.8% of the country’s total population (17,076,076). The Mapuche were the most numerous (almost 1,800,000 individuals), followed by the Aymara (156,000) and the Diaguita (88,000) (Source: INE, Chile, 2017). A sustained increase in the urban Indigenous population over the rural is noteworthy, now accounting for 87.8% with only 12.2% living in rural areas (Source: INE, Chile, 2017).

Chile has a lot of places where indigenous or tribal tourism offers a lot of potential. The communities’ openness to tourism and their involvement in the tourism sector are significantly empowering Chile to augment its potential for socio-economic development.

An Overview of Tribal Tourism in Contemporary Chile

The Chilean government, like many of its Latin American counterparts, has chosen ‘touristification’ for neoliberal economic growth. This has caused numerous conflicts with ethnic groups, like the developmental activities associated with tourism, like ‘mining’ in the North and the ‘hydro-electric’ and ‘forestry’ in the South. However, three regions have shown a significant amount of progress in this regard – The Araucanía Region, San Pedro and Easter Island (Rapa Nui) (la Maza, 2017).

The Araucanía Region, located in south-central Chile, is historically home to the Mapuche people, while in the north, the Atacameño (Likan Antay) communities inhabit the Atacama Desert. Its interest for tourism is based both on a main town that contains Andean architecture and on the cultural and natural attractions of the surrounding area. The area maintains a strong tourist demand year-round and is consolidated in the national and international tourism markets. Based on 2002 census data, the Sistema Nacional de Información Municipal estimated the population of the comuna in 2016 to be 7626, 60.9 per cent of which were indigenous. The region boasts more than 80 tourist attractions that include highland lakes, archaeological sites, hot springs, volcanoes, geysers and villages with traditional Andean architecture (SERNATUR ANTOFAGASTA, 2014). Large tourism companies have become established there, which offer a full range of services.

In San Pedro de Atacama, tourism is a consolidated industry that continues to expand alongside mining. Tourism businesses in the town have benefited from a relatively low tax burden and a rudimentary tourism policy (Bolados, 2014b). Indigenous communities also face the effects of mining activities in their territories, which also compete with demands for land, water and other resources associated with tourism (Yáñez and Molina 2008).

Easter Island lies in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, 3,700 km from Latin America. Easter Island is inhabited by the Rapa Nui, indigenous peoples of Polynesian origin. It is one of Chile’s greatest tourist attractions, with cultural heritage, scenery and natural resources that draw international visitors (Ramírez, 2004). The island is largely known for the moais, or ancient monolithic human figures carved by the Rapa Nui, followed by performances of Polynesian dance and culture such as the Tapati celebration (Acuña, 2012). 66% of the island’s attractions are of ethnic-cultural origin (CODESSER, 2014).

Discussion and Findings

Comparative Analysis

According to Prof. Pandey and Dr Bathla (2023), although tribal communities possess sovereignty and institutions to govern their affairs, the influx of short-term tourists (STT) can negatively impact cultural habitats and contribute to biodiversity loss. The integration of tribal groups into the prevailing societal framework may result in their fragmentation as they endeavour to adapt to the challenges posed by this evolving paradigm. Tourism, especially in prominent destinations, remains a volatile and precarious source of income due to its sensitivity to environmental and social fluctuations.

Tourism has been associated with a range of issues, including economic exploitation, cultural decline, and environmental degradation, particularly in the well-visited tourist destinations (Singh, 2005). According to Hassan (2008), the projected increase in tourism has the potential to exacerbate these challenges.

Tourism in regions such as San Pedro de Atacama features numerous activities managed by indigenous local communities themselves. This presents a promising roadmap for India’s tribal tourism, as it not only contributes to the economic development of tribal communities but also fosters their social empowerment within the broader Indian context.

In San Pedro de Atacama, tourism is a well-established industry that continues to grow alongside mining. Local tourism businesses have benefited from a relatively low tax burden and minimal regulatory oversight (Bolados, 2014b). In contrast, tribal tourism in India is primarily implemented through a top-down approach. Although this model provides certain benefits—such as the ‘1000 Tribal Home Stays’ initiative promoted under the Swadesh Darshan scheme to boost local tourism and livelihoods in tribal areas (PIB, 2024)—it often lacks the grassroots involvement seen in Chile.

Things can also take a negative turn, as evidenced by the Chilean experience. Easter Island, a geographically isolated territory inhabited by the Rapa Nui people, became a focal point for tourism development due to its significance as a major tourist attraction. While various studies were conducted to promote tourism in the region, these developments ultimately had adverse effects, threatening the traditional lifestyle and cultural integrity of the island’s indigenous population.

The fact that Easter Island is an international tourism destination gave weight to actions such as the occupation of the park and the expulsion of park officials, providing Rapa Nui leverage in negotiations over their demands. It also opened the way for full transfer of administrative control over the territory in the future, setting a precedent for indigenous management of tourist activities in other protected areas linked to indigenous territories (la Maza, 2017).

The discourses and symbols of cultural difference mobilised by Atacameño communities have served as a useful tool to advance their territorial and autonomy demands in a context of weak recognition (Fuentes and de Cea, 2017) and neoliberal economic policies. A similar strategy could empower Indian tribal communities to assert their rights while actively engaging with tourism frameworks. In India, although both the government and private sector contribute significantly to the growth of the tourism industry and the improvement of livelihoods, tribal groups must retain control over these initiatives. This is crucial not only for preserving their rich cultural heritage but also for establishing clear boundaries for sustainability—an issue highlighted in the case study by Prof. Pandey and Dr Bathla (2023).

Recommendations

Based on the comparative analysis, the following recommendations are proposed for government agencies, tourism operators, and indigenous communities to collaboratively enhance tribal tourism in India:

Policy and Institution

Effective policies must prioritise the cultural rights of tribal communities, prevent exploitation and advance long-term sustainability. This approach aligns with the successful implementation of Swadesh Darshan 2.0 and Chile’s policy framework. They should also maintain low tax burdens and reflect the unique cultural and geographic character of each region.

In Chile, a number of institutions like the National Corporation for Indigenous Development (CONADI), the Agricultural Development Institute (INDAP), the National Tourism Service (SERNATUR), and the National Forestry Corporation (CONAF) work in parallel at both the national and regional levels to advance indigenous tourism.

Similarly, in India, ministries such as the Ministry of Tourism, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, along with respective state tourism and indigenous affairs departments, must collaborate through an integrated approach. A fragmented or unilateral strategy hampers the effective utilisation of India’s vast potential for the development of the tribal tourism industry.

Public-Private-Tribal Partnerships

While public–private partnerships have made notable strides in areas such as marketing and transportation, certain ethical concerns remain unresolved. Practices like photographing tribal people without consent, offering liquor or cigarettes within village premises, or stopping tourist buses along highways that cut through the Jarawa tribe’s habitat to observe them “naked” or offer spicy food—which can make them susceptible to illness— highlight serious ethical violations. As noted by Sonia Sarkar in the South China Morning Post (Sarkar, 2024), these actions underscore the urgent need to respect the dignity, self-esteem, and autonomy of tribal communities. Such values must never be compromised for the sake of entertainment or commercial tourism profits.

Public–private partnerships must expand to include active participation from tribal communities. Drawing lessons from the Chilean experience—particularly the Rapa Nui people’s eventual administrative control over Easter Island’s protected areas—India must strive to empower its tribal communities to directly manage and benefit from tourism initiatives within their own territories.

Tribal representatives should be incorporated into tourism boards and decision-making committees to ensure inclusive governance. Tourism packages and activities must be designed in consultation with tribal councils, while promoting community-run homestays, local guides, and indigenous craft markets with financial and logistical support from private enterprises. Additionally, community-led codes of conduct for tourists should be established to safeguard cultural integrity and ensure respectful engagement.

Additionally, strict regulations and targeted awareness campaigns must be implemented to prevent practices such as unsolicited photography, culturally insensitive behaviour, and the offering of prohibited items like alcohol and tobacco. Public–private–tribal partnerships should prioritise not only economic benefits but also the preservation of cultural heritage, ecological sustainability, and the overall well-being of indigenous communities.

Land Rights Protection and Indigenous Administration

Most importantly, as a decisive and essential step, the protection of tribal land rights and administrative autonomy must be treated as a top priority. For indigenous communities, land is not merely a physical resource—it is deeply intertwined with their ancestral heritage, spiritual beliefs, and collective identity. Any intrusion or unregulated tourism development within these territories poses a serious threat, not only to their livelihoods but also to their cultural and spiritual survival.

Legal provisions such as the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, must be appropriately amended to explicitly address tourism-related land and site rights, ensuring that commercial tourism interests do not override the forest and cultural rights of tribal communities. The Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA), should be strengthened to empower Gram Sabhas with decisive authority over tourism projects within their jurisdictions. Moreover, as infrastructure development often involves land acquisition, such processes must be conducted with cultural sensitivity under the Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (LARR) Act, 2013, recognising the ancestral ties and spiritual significance these lands hold for tribal communities. A culturally sensitive, rights-based approach grounded in existing legal safeguards is indispensable for promoting sustainable, ethical, and inclusive tribal tourism in India.

While tourism is vital, it is equally important to ensure that indigenous communities are equipped to participate in tourism sustainably and on their own terms. Capacity-building initiatives should aim to equip tribal populations with the necessary skills while honouring and preserving their cultural values and traditions. Law and order within tribal tourism zones must be overseen by the respective state forest departments and other relevant institutions, with a firm emphasis on ensuring that administrative control over tourism activities remains with indigenous governing bodies such as Gram Sabhas and tribal councils. This approach is key to maintaining cultural integrity, safeguarding community autonomy, and promoting orderly, responsible tourism management.

Conclusion

Tribal tourism in India intersects vital concerns—cultural preservation, sustainable livelihoods, and indigenous rights. While tribal communities possess a rich and diverse cultural heritage, their traditional ways of life face increasing pressures from expanding tourism industries, often driven by commercial interests. The experiences from regions such as San Pedro de Atacama and Easter Island in Chile offer valuable lessons for India, where the growing focus on tourism in tribal areas necessitates a careful, culturally sensitive, and rights-based approach to ensure that tourism benefits indigenous populations without compromising their identity, sovereignty, or ancestral lands.

This study’s comparative analysis reveals that while tourism offers potential for economic growth and social empowerment for tribal communities, it can also lead to cultural fragmentation, environmental degradation, and exploitation if not properly regulated. The Chilean model, particularly the eventual administrative control secured by the Rapa Nui over their protected areas and the participatory practices of the Atacameño communities, demonstrates the effectiveness of indigenous leadership in managing tourism sustainably. In contrast, India’s predominantly top-down tourism policies, despite initiatives like Swadesh Darshan, often sideline tribal communities from decision-making processes, limiting their ability to safeguard their culture and land rights. Furthermore, the documented challenges, such as unsolicited photography, cultural insensitivity, and inappropriate tourist behaviours, highlight the urgent need for comprehensive frameworks that prioritise the dignity and welfare of tribal populations.

Based on these findings, the study recommends a reorientation of tribal tourism frameworks in India with tribal communities placed at the centre of governance, administration, and benefit-sharing mechanisms. Policies must emphasise the protection of tribal culture, uphold indigenous land rights, and foster culturally sensitive tourism practices. Structured capacity-building initiatives should be introduced to properly organise and train indigenous communities for active, responsible participation in tourism, ensuring that the economic and social benefits reach them while preserving cultural integrity. The financial proceeds from tribal tourism activities should directly flow to the respective tribal panchayats, ensuring that the economic gains contribute to the welfare, infrastructure, and cultural initiatives of the local communities. Public-private partnerships should be expanded to include tribal councils and representatives as equal stakeholders in the design and regulation of tourism initiatives. Additionally, legal provisions such as the Forest Rights Act (2006), PESA Act (1996), and LARR Act (2013) must be suitably amended and stringently enforced to guarantee indigenous administrative autonomy over tourism projects within their territories.

This study is limited by its reliance on secondary case studies and publicly available policy analyses, without direct engagement with tribal communities or field-based data collection in Indian tribal tourism sites. Further research should include ethnographic fieldwork and impact assessments to capture tribal perspectives on tourism’s socio-cultural and economic consequences. Future studies may also evaluate the long-term outcomes of indigenous-led governance models and explore region-specific policy reforms to enhance tribal autonomy amid increasing tourism. The author acknowledges the use of AI-based tools to enhance the editorial and linguistic quality of this paper.

Title Image Courtesy: https://latest.sundayguardianlive.com/news/

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and the Defence Research and Studies

Acknowledgment:

I sincerely thank Gp Capt (Dr) R Srinivasan for his guidance and support throughout this research. I am also grateful to Gp Capt Parthasarathi, IG Santosh Chandran, and Cdr Ashok Dua, PhD, for their valuable insights and encouragement.

References

Acuña, Á. (2012). Tapati Rapa Nui: La reconstrucción de un espacio mítico en contexto turístico. In R. Asensio & B. P. Galán (Eds.), El turismo es cosa de pobres? Patrimonio cultural, pueblos indígenas y nuevas formas de turismo en América Latina (pp. 73–84). Colección PASOS.

Agoramoorthy, G., & Sivaperuman, C. (2014). Tourism, tribes and tribulations in Andaman Islands. Current Science, 106(2), 141. Retrieved June 18, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v106/i2/141-141

Bandhu, A. (2024). A study of tribal tourism with special reference to India by using GIS techniques. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science, 12(7), 95–104. https://www.questjournals.org/jrhss/papers/vol12-issue7/120795104.pdf

Bolados, P. (2014b). Procesos transnacionales en el salar de Atacama-norte de Chile: Los impactos de la minería y el turismo en las comunidades indígenas atacameñas. Intersecciones en Antropología, 15, 431–443.

Buultjens, J., & Gale, D. (2013). Facilitating the development of Australian Indigenous tourism enterprises: The Business Ready Program for Indigenous Tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 5, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.11.003

Census of India. (2011). Census of India 2011. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

Choubey, J. (2013, May 15–31). A report warns that increasing contact through tourism may make the native tribals more vulnerable to diseases. Down to Earth. Retrieved April 30, 2025, from https://www.downtoearth.org.in

CODESSER [Corporación de Desarrollo Social del Sector Rural]. (2014). Dirección técnica para la formulación del plan estratégico de turismo. Santiago: CODESSER. Retrieved May 26, 2025

de la Maza, F. (2018). Tourism in Chile’s indigenous territories: The impact of public policies and tourism value of indigenous culture. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies, 13(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17442222.2018.1416894

Fuentes, C., & de Cea, M. (2017). Reconocimiento débil: derechos de pueblos indígenas en Chile. Perfiles Latinoamericanos, 25(49), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.18504/pl2549-003-2017

Government of India. (2013). Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2025, from https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A2013-30.pdf

Hassan, H., Habil, H., & Mohd Nasir, Z. (2008). Persuasive strategies of tourism discourse. New Perspectives in Language and Communication Research, 1–19.

Kumar, S. (1999). Measles outbreak among the Jarawa tribe. The Lancet, 354(9187), 1624.

Mazumdar, P. (2018, December 7). Hornbill festival: Enthusiasm marred by tourist’s criticisms. The New Indian Express. Retrieved May 22, 2025, from https://www.newindianexpress.com/thesundaystandard/2018/Dec/07/hornbill-festival-enthusiasm-marred-by-tourists-criticisms-1908589.html

Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India. (1996). The Panchayats (Extension to the Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://panchayat.gov.in

Ministry of Tourism, Government of India. (n.d.). Year-wise details of projects sanctioned by ministry under tribal circuit/theme of Swadesh Darshan. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://data.gov.in/resource/year-wise-details-projects-sanctioned-ministry-under-tribal-circuittheme-swadesh-darshan

Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India. (2014). Report of the High-Level Committee on Socio-Economic, Health and Educational Status of Tribal Communities of India. Retrieved May 22, 2025, from https://tribal.nic.in/downloads/other-important-reports/XaxaCommitteeReportMay-June2014.pdf

Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India. (2006). The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006. Retrieved June 17, 2025, from https://tribal.nic.in/FRA.aspx

National Institute of Statistics (INE), Chile. (2017). Censo 2017: Resultados definitivos. Gobierno de Chile. Retrieved May 22, 2025, from https://www.censo2017.cl

Pandey, P. C., & Bathla, G. (n.d.). Developing a sustainable tribal tourism model in the tribal region of Jharkhand, India [Unpublished manuscript]. SOHMAT, CT University, Ludhiana, Punjab, India.

Press Information Bureau. (2014, August 7). Scheduled Tribes and other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006: Rights of tribals and forest dwellers. Government of India, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. Retrieved July 23, 2025, from https://www.pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=108222

Press Information Bureau. (2024, September 19). 1000 tribal home stays to be promoted under Swadesh Darshan to boost local tourism and livelihood in tribal areas. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. Retrieved May 22, 2025, from https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2056682

Ramírez, J. M. (2004). Manejo del recurso arqueológico en Rapa Nui: Teoría y realidad. Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena, 36, 489–497. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-73562004000300049

Sasikumar, M. (2018). The Sentinelese of North Sentinel Island: A reappraisal of tribal scenario in an Andaman Island in the context of killing of an American preacher. Journal of Social Sciences, 54(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277436X20180104

SERNATUR ANTOFAGASTA [Servicio Nacional de Turismo]. 2014. Plan de Acción Región de Antofagasta Sector Turismo 2014-2018. Gobierno de Chile: SERNATUR.

Servicio Nacional de Turismo (SERNATUR). (2014). Plan de acción región de Antofagasta sector turismo 2014-2018. Gobierno de Chile. Retrieved May 22, 2025

Singh, P. (2006). The islands and tribes of Andaman and Nicobar. Delhi, India: Prakash Books.

Singh, S. (2005). Secular pilgrimages and sacred tourism in the Indian Himalayas. GeoJournal, 64(3), 215–223.

Sarkar, S. (2024, April 14). ‘Destructive’: Tribes in India at risk as expanding tourism plans threaten cultural identity, ecosystem. South China Morning Post. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/lifestyle-culture/article/3258931/destructive-tribes-india-risk-expanding-tourism-plans-threaten-cultural-identity-ecosystem

World Tourism Organization. (2023, December 7). Tourism Doing Business: Investing in Chile. Retrieved May 26, 2025, from https://www.unwto.org/investment/tourism-doing-business-investing-in-chile

Yáñez, N., & Molina, R. (2008). La gran minería y los derechos indígenas en el norte de Chile. LOM Ediciones.