The South China Sea struggle remains a strong source of pressure in Southeast Asia. Straddling a deliberately crucial sea path, Indonesia, even though not a claimant state, finds itself profoundly embroiled in the debate. This consideration digs into Indonesia’s multifaceted approach to exploring this complex geopolitical landscape. The research examines Indonesia’s essential part in the Affiliation of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). As a driving part, Indonesia champions the standards of ASEAN centrality and consensus-based choice-making. This approach seeks to cultivate territorial solidarity and create a serene discourse among clashing parties. The research investigates how Indonesia leverages its conciliatory impact inside ASEAN to advocate for selecting a Code of Conduct (COC) in resolving the South China Sea, pointing to setting up a system for overseeing pressures and advancing dependable behaviour.

Introduction

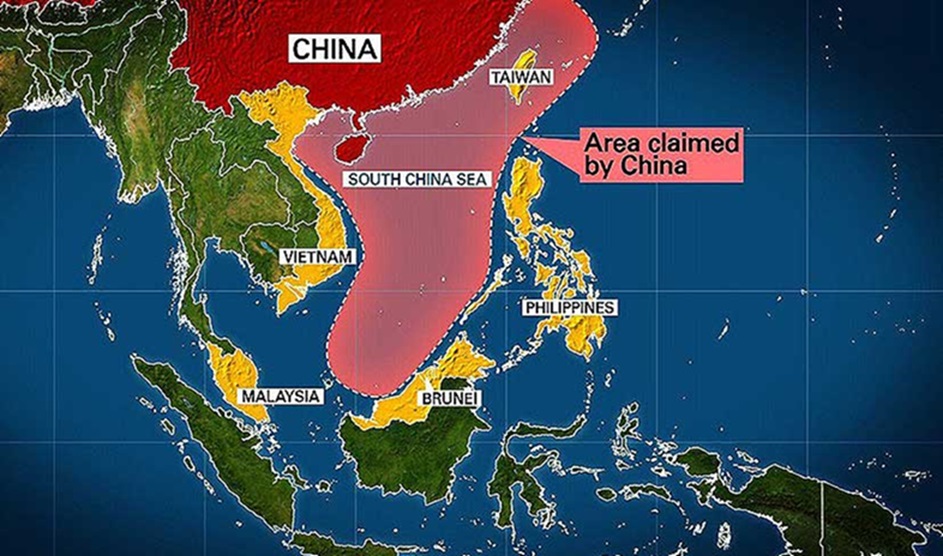

Multiple nations fight over territory and resources in the South China Sea, a simmering geopolitical hotspot. Through a contentious “nine-dash line,” China claims a large portion of the sea, which includes islands, reefs, and important shipping lanes. This far-reaching guarantee straightforwardly goes against the regional cases of Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan. The central question fixates on islands like the Spratly, accepted to be wealthy in normal assets. These competing claims frequently result in tense standoffs between coast guards and occasional incidents, such as the recent clash between China and the Philippines near the Second Thomas Shoal. With critical financial interests and fundamental contention, the South China Ocean struggle remains a likely flashpoint in Asia. The South China Sea holds gigantic importance for Indonesia, woven into the texture of its economy, security, and strategy. Monetarily, the ocean fills in as a crucial exchange course. Indonesia’s archipelagic topography implies essential delivery paths for worldwide trade across its waters. Interruptions because of contention could handicap Indonesian exchange, affecting its development and global standing. The South China Sea is additionally considered wealthy in normal assets, including fish and expected oil and gas reserves. Unobstructed admittance to these assets is pivotal for Indonesia’s energy security and monetary prosperity. Security concerns additionally pose a potential threat. Indonesia, however not a petitioner in the contested domains, has a tremendous Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) reaching out from its islands into the South China Sea. This area is important to the economy and also represents sovereign territory. Any infringement by different countries, especially decisive activities by China, is viewed as a danger to Indonesia’s regional uprightness. Furthermore, the potential for a more extensive clash in the district raises security worries, as Indonesia would probably be attracted because of its geological nearness. Decisively, the South China Sea is an essential support zone for Indonesia. Indonesia’s influence in the region could be diminished by China which controls the region. This could upset the delicate balance of power in Southeast Asia. Indonesia likewise tries to play a position of authority in ASEAN, and a quiet goal toward the South China Sea question is vital for keeping up with territorial dependability and encouraging monetary collaboration. Subsequently, Indonesia navigates a precarious situation, keeping up with financial binds with China while supporting adherence to international laws set by UNCLOS.

Research Questions

- What is Indonesia’s role in ASEAN?

- What are Indonesia’s efforts to strengthen maritime cooperation?

- What will be the impact on regional stability?

Literature Review

The South China Sea dispute poses a critical challenge to territorial soundness. Indonesia, a key Southeast Asian player, takes a one-of-a-kind approach. Research highlights Indonesia’s centre-on strategy through ASEAN, supporting a Code of Conduct (COC) with China. Furthermore, investigating Indonesia’s legitimate technique, attests to its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) claims beneath UNCLOS. This research lays the foundation for analyzing the viability of Indonesia’s endeavours in exploring this complex geopolitical issue.

Historical Context

The South China Sea stews with pressure. Numerous nations stake cases to islands, archipelagos, and oceanic assets inside its tremendous scope. This complex international issue has roots that stretch back hundreds of years, energized by verifiable translations, moving influence elements, and the charm of undiscovered wealth. Early history illustrates a district where control vacillated between provincial realms and pioneer powers. However, China has maintained its historical dominance. A Kuomintang government map in 1947 produced the infamous “nine-dash line,” a U-shaped boundary encompassing almost the entire South China Sea. The Second World War was a turning point. Japan’s loss in 1945 remained a lawful hazy situation. The San Francisco Deal constrained Japan to surrender command over the involved islands, however it didn’t expressly grant sway to some other country. China considered this to be an open door, emphasizing its authentic cases. The 1960s and 70s saw a scramble for assets. Because of the monetary capability of the South China Sea, wealth in fisheries, and possibly huge oil and gas reserves, rivalry strengthened. Nations began involving islands, frequently through military activities. Strains erupted in 1974 when China held onto control of the Paracel Islands from Vietnam in a horrendous conflict. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS) offered a system for settling sea questions. Nonetheless, the translation of UNCLOS arrangements, especially regarding the legitimate status of highlights like islands and reefs, stays challenged. China, for example, demands its sweeping cases fall under verifiable privileges, an idea not completely upheld by UNCLOS. In a milestone 2016 case, the long-lasting Court of Mediation in The Hague voted down China’s cases in light of the nine-dash line, naming it over the top. China, nonetheless, dismissed the decision, further stressing relations. Chinese assertiveness has increased in recent years. Enormous scope land recovery projects have changed reefs into fake islands fit for facilitating army bases. As a result, concerns about the region’s potential militarization and freedom of navigation have arisen. The South China Sea conflict’s historical context reveals the intricate interplay of factors. From contending authentic accounts to the disclosure of important assets, the seeds of this question were planted quite a long ago. The absence of an unmistakable lawful goal and China’s developing power keep the locale nervous.

Recent Evolution of Conflict

The conflict in the South China Sea has entered a new phase characterized by growing militarization. China’s activities have been alarming. Through huge scope land recovery projects, China has changed delicate reefs into counterfeit islands fit for facilitating military offices. This incorporates airstrips, radar establishments, and arrangements of surface-to-air rockets. These activities harden China’s regional cases and venture into huge military power. To challenge China’s territorial claims, these operations involve sending US warships close to disputed features. This blow-for-blow show of the military could raise fears of inadvertent conflicts and possible heightening. Vietnam, for example, has put resources into waterfront protections and bought military gear. Tensions are getting even uglier as a result of this regional arms race. The eventual fate of the South China Sea remains questionable. Whether exchange and discretion can supplant the ongoing direction of militarization will decide the course of this complex international issue.

International Legal Framework for the South China Sea (UNCLOS)

The South China Sea debate unfurls against the scenery of the United Nations Convention on the Law of Sea (UNCLOS). This far-reaching structure lays out a lawful request for seas and oceans, framing expectations of beachfront states. UNCLOS awards beachfront states sway more than a 12-nautical mile regional ocean, where they can practice unlimited oversight. The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which extends 200 nautical miles from the baseline, lies beyond that. Inside the EEZ, seaside states hold selective privileges to investigate and take advantage of assets like fisheries and seabed minerals. Be that as it may, the opportunity of route and overflight remains ensured for all countries. The interpretation of UNCLOS provisions is the central issue in the dispute over the South China Sea. China’s broad cases, frequently founded on verifiable stories, conflict with the idea of EEZs. Highlights like reefs and low-tide rises, bountiful in the South China Sea, further muddle matters. China uses the ambiguity that UNCLOS provides regarding its legal status to support its claims. UNCLOS continues to be an important tool despite its limitations. The 2016 arbitral honour in the Philippines-China case, because of UNCLOS, discredited China’s broad cases utilizing the nine-dash line. However not restricting, the decision fills in as a legitimate reference point for future exchanges. The outcome of UNCLOS in the South China Sea depends on the entirety of the gatherings’ eagerness to stick to its standards. Maintaining the opportunity of route, regarding EEZs, and resolving debates through serene means illustrated in UNCLOS are essential strides toward a more steady and secure South China Sea.

Importance of UNCLOS in Resolving the Conflict

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) offers an essential, but flawed, structure for settling the South China Sea struggle. This is why:

- Legitimately Restricting Standards: UNCLOS gives a bundle of globally perceived rules overseeing sea communications. These guidelines address issues like regional cutoff points, asset abuse, and opportunity of route. Negotiations based on established principles are made possible.

- Settlement Systems: UNCLOS frames serene means for settling debates. According to the convention, mediation and arbitration can result in either legally binding or non-binding agreements. These components offer an option in contrast to one-sided activities and military acceleration.

- Authenticity and Impartiality: UNCLOS appreciates far-reaching acknowledgement as a classified collection of global regulations. This impartiality gives a shared belief to dealings and deters one-sided understandings given verifiable stories. The arbitral decision in 2016 that was based on UNCLOS principles demonstrated its ability to challenge large claims.

- Strength and Consistency: Maintaining UNCLOS standards in the South China Sea can cultivate dependability and consistency for all partners. Adherence to EEZs and the opportunity of route guarantees unrestricted oceanic exchange and asset investigation, helping all countries.

Indonesia’s Strategies for Conflict Resolution

Indonesia, a central participant in the South China Sea question, steps cautiously. While it has sea claims in the Natuna Islands area, it focuses on compromise and adherence to global regulation. Indonesia’s essential methodology is tact. It effectively participates in local gatherings like ASEAN to advance exchange and collaboration. This approach cultivates a guidelines-based request and beats one-sided activities down. Moreover, Indonesia underscores the significance of quiet settlement systems framed in UNCLOS, including assertion and intercession. Indonesia’s obligation to global regulation is apparent. It has taken part in UNCLOS dealings and sanctioned the show. By sticking to UNCLOS standards, Indonesia reinforces its cases given the idea of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and the opportunity of route.

Indonesia’s Initiatives to Promote Adherence to UNCLOS

Indonesia champions UNCLOS adherence in the South China Sea. It effectively takes part in provincial gatherings, encouraging exchange and collaboration in light of UNCLOS standards. Indonesia advances a guidelines-based request that beats intense activities by underscoring tranquil settlement components like an intervention. Moreover, its sanction of UNCLOS fortifies its situation and urges others to follow accordingly. Indonesia takes care to balance its claims with maintaining good relations with China. In general, Indonesia’s drives advance UNCLOS as an essential device for settling the contention calmly and legitimately.

Role of ASEAN in Managing the South China Sea Dispute

The Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) possesses a focal job in dealing with the South China Sea debate. However, its unique approach hinders its effectiveness. ASEAN focuses on the agreement-based independent direction. This discourages unilateral actions while encouraging regional dialogue. It leads drives like the Announcement on the Direct of Gatherings in the South China Sea, focused on calmly overseeing questions. Nonetheless, agreeing can be slow, impeding areas of strength for emphatic activities. Keeping up with non-partisanship. Given its assorted participation, some with covering claims, ASEAN tries not to favour one side. This lack of bias permits it to stay a stage for correspondence between all gatherings. ASEAN does not have any enforcement mechanisms or a military force. It ensures agreement compliance through moral persuasion and international pressure. Because of this, it is unable to prevent aggressive behaviour. Despite restrictions, ASEAN stays critical. It provides a crucial forum for discussion and promotes peaceful alternatives to military conflict. As ASEAN reinforces its interior solidarity and tracks down ways of utilizing global help, its part in dealing with the South China Sea debate can be more effective.

Indonesia’s Contributions and its Impact on Regional Stability

The stewing strains in the South China Sea represent a critical danger to local security. Indonesia has become a crucial player in this complex international scene, utilizing its authority inside the Relationship of Southeast Asian Countries (ASEAN) to push for a tranquil goal through the Code of Conduct (CoC) discussions. Indonesia’s commitments to the CoC interaction go past basic investment. During its 2023 chairmanship of ASEAN, Indonesia sped up the talks. It reached a significant milestone by passing the draft CoC framework’s second reading. This implies significant advancement in laying out a bunch of rules overseeing the direction of gatherings in the contested waters. Indonesia assumed an essential part in facilitating the CoC exchanges between ASEAN and China cultivating direct discourse between the key partners. Moreover, by wanting to have the following round of discussions in the not-so-distant future, Indonesia shows its obligation to keep up with energy and drive the cycle towards an effective end. Indonesia’s methodology reaches out past the exchange table. Indonesia champions practical maritime cooperation between ASEAN and China in the South China Sea because it recognizes the significance of trust-building measures. This two-dimensional system – propelling the CoC and encouraging collaboration expects to establish a steadier climate through shared exercises and a common perspective of global standards. This proactive position has earned worldwide acknowledgement, featuring Indonesia’s basic job in tracking down a quiet arrangement through ASEAN’s aggregate endeavours. An obvious code would lay out a structure for quiet debate settlement, forestalling one-sided activities and diminishing the gamble of military heightening.

Indonesia’s Efforts to Strengthen Maritime Cooperation

In the South China Sea, Indonesia actively works to improve maritime cooperation. It promotes joint initiatives with regional players, including China, outside of the CoC negotiations. This participation takes different structures:

Joint patrols and exercises: Indonesia takes part in exercises like AMEX to improve communication and interoperability. Furthermore, it investigates opportunities for joint watches with different petitioners for exercises like an enemy of robbery or search and salvage.

Protection of the marine environment: Pollution and overfishing pose environmental risks in the South China Sea. Indonesia pushes for cooperative endeavours to address these difficulties, guaranteeing an economic future for the locale.

Logical examination coordinated effort: The South China Sea holds immense potential for logical exploration. Indonesia empowers joint examination adventures, encouraging information sharing and serene investigation of the locale’s assets. By advancing these helpful measures, Indonesia means to make a common stake in the South China Sea’s prosperity, cultivating trust and lessening pressures among contending petitioners.

Confidence-Building Measures

Indonesia places diplomacy and legal frameworks like the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) first, but it also recognizes the significance of Confidence-Building Measures (CBMs) for reducing tensions in the South China Sea. This is the way Indonesia takes an interest:

Military Activities: Indonesia effectively partakes in multilateral military activities like the ASEAN Oceanic Activity (AMEX) and the Malabar series with India, the US, and Japan. These activities advance straightforwardness, interoperability, and correspondence between territorial militaries, encouraging trust and lessening the gamble of errors adrift.

Hotlines and Correspondence Channels: Indonesia upholds laying out hotlines and correspondence channels between territorial coast gatekeepers and naval forces. This works with direct correspondence in the event of episodes adrift, considering de-heightening and tranquil goals of false impressions.

Challenges and Limitations of Indonesia’s Approach

Indonesia’s approach to the South China Ocean strife prioritizes strategy and territorial consensus-building through ASEAN, the Affiliation of Southeast Asian Countries. This procedure has merits in cultivating discourse and steadiness but faces challenges. A key quality is Indonesia’s non-partisanship. Not being a claimant state permits it to act as an arbiter, empowering participation over showdown. In any case, this non-partisanship can be seen as a shortcoming by claimant states looking for more grounded activity against China’s confident actions. Another challenge is the moderate pace of ASEAN decision-making, which depends on agreement. This can be baffling when managing with an effective player like China, who may not be as contributed in finding a quick determination.

Conclusion

Indonesia’s part in the South China Sea struggle is multifaceted. As a driving part of ASEAN, Indonesia champions territorial centrality and consensus-based arrangements. It leverages its discretionary impact to thrust for tranquil resolutions through systems like the Code of Conduct (COC). Activities to combat IUUF and maintain flexibility of route illustrate Indonesia’s commitment to universal law and utilization of the South China Sea. However, Indonesia’s approach is not without challenges. Adjusting its financial ties with China and its commitment to territorial security requires a fragile act. Regional attacks and emphatic activities from China proceeded to test the limits of Indonesia’s strategy. Whereas Confidence-Building Measures can cultivate discourse, accomplishing an enduring arrangement pivots on the readiness of all parties included to regard universal law and lock in great confidence negotiations. Despite these challenges, Indonesia’s endeavours play a pivotal part in keeping up territorial solidness. By cultivating a rules-based arrangement and advancing participation, Indonesia makes an environment where pressures can be de-escalated and exchange can take root. The victory of Indonesia’s methodology will depend on its capacity to keep ASEAN’s solidarity, reinforce territorial sea security, and energize a commitment to quiet arrangements from all claimants. Ultimately, a steady and affluent South China Sea requires collective exertion. As long as Indonesia proceeds to win these values, it will stay an imperative player in forming the future of the South China Sea.

Title image courtesy: Dynamite News

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies

Bibliography

Aprianto Trianggoro Putro, E. L. (2023). Indonesian Leadership Policies and Strategies In Facing The South China Sea Conflict. International Journal Of Humanities Education And Social Sciences, 8.

Aprilla, W. (2021). Indonesia’s Efforts in Resolving South China Sea Conflict. International Journal on Social Science, Economics and Art, 7.

Haniff Ahamat, S. M. (2023). CHINA’S SOUTH CHINA SEA CLAIMS, . JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, 35.

Renaldi, F. T. (2023). Overview of Indonesia’s Role in the South China Sea Conflict. : Journal of Education Technology Information Social Sciences and Health, 8.