The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed in 1960 between India and Pakistan, has often been praised as one of the few successful examples of water diplomacy in a conflict-prone region. Despite multiple wars, political tensions, and decades of hostility, the treaty has managed to survive, allowing both countries to share the Indus River system’s waters. However, in recent years, the IWT has become more than just a water-sharing agreement. It has slowly emerged as a subtle tool of geopolitical leverage, especially for India, which holds the upper-riparian position.

This research explores how the Indus Waters Treaty fits into the broader strategic and geopolitical landscape of South Asia today. It analyses whether India can use its legal and technical rights under the treaty to indirectly pressure Pakistan without actually violating the agreement. The study also examines Pakistan’s heavy reliance on the Indus River for its agriculture and economy, which makes any shift in water availability a serious national security concern for Islamabad. Additionally, the paper discusses how recent political events, cross-border conflicts, and the impact of climate change have further complicated the treaty’s future relevance.

Using a qualitative research approach based mainly on secondary sources like official documents, academic studies, and expert analyses, this paper aims to present a balanced understanding of the Indus Waters Treaty’s evolving role. The findings suggest that while the IWT continues to serve as a stabilising framework, it also holds the potential to become a significant strategic instrument in the complex and sensitive India-Pakistan relationship.

Introduction

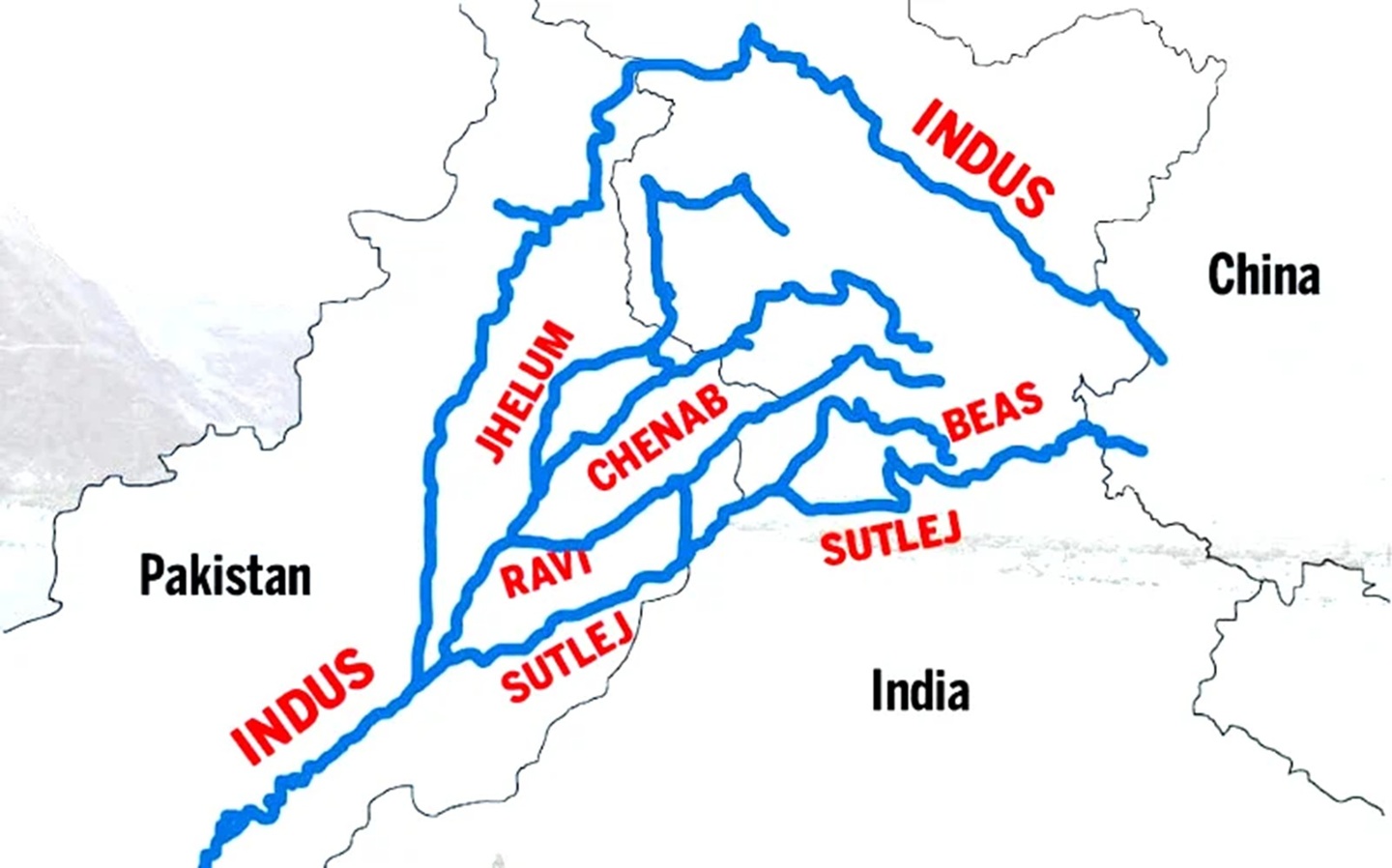

Water, the lifeblood of civilisation, is increasingly emerging as a central theme in international relations, especially in regions marked by historical animosity, contested borders, and climatic vulnerability. The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed on September 19, 1960, under the auspices of the World Bank, between India and Pakistan, is one of the most comprehensive and enduring transboundary water-sharing agreements in the world. The treaty allocated the three eastern rivers, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej, to India, while granting Pakistan the rights over the three western rivers, Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab. Despite being brokered at a time of political instability and mistrust, the IWT has survived three full-scale wars, multiple border skirmishes, and decades of political turbulence. It is often cited as a rare success story of water diplomacy in a conflict-prone region.

However, what appears on the surface as a technical and cooperative framework is underpinned by deep-seated geopolitical realities. The treaty, while hailed for its durability and neutrality, is inherently asymmetrical with India, as the upper riparian state, wielding considerable geographical and infrastructural power over the flow and development of the western rivers. Over the decades, this asymmetry has taken on a strategic character, particularly as the India-Pakistan relationship has grown more adversarial and securitised.

In recent years, particularly after events such as the 2016 Uri attack, the 2019 Pulwama terror incident, and the abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu & Kashmir, the IWT has resurfaced in political and strategic discourse as more than just a hydrological agreement. Statements from Indian political leaders, including threats to “utilise every drop” of the Indus waters, have reignited debates over whether India could or should leverage its upper-riparian status as a non-military tool of pressure against Pakistan. Though India has never formally violated the treaty, the symbolic invocation of its potential suspension or modification reflects a broader shift in strategic thinking: where natural resources are not only environmental assets but also instruments of national power.

Moreover, the global strategic landscape is shifting. With rising water insecurity due to climate change, glacial retreat in the Himalayas, irregular monsoon patterns, and rapid population growth, water has become a scarce and contested resource. South Asia, home to nearly 25% of the world’s population but just 4% of its freshwater, is entering an era of intensified hydro-political contestation. In this context, the Indus Waters Treaty assumes a dual identity: as a tool of peacebuilding on one hand and as a latent source of geopolitical leverage and contention on the other.

The strategic value of the treaty is further amplified by its legal rigidity and diplomatic weight. Being internationally mediated and rooted in international water law principles, the IWT is not easy to amend or abrogate unilaterally. Yet, it provides India with several technical and procedural instruments, such as the construction of run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects, maximising permissible storage, and delayed flow mechanisms, which can be used to subtly alter the water equation without formally breaching the treaty. These tools allow India to signal discontent or exert pressure on Pakistan without crossing overt red lines that would provoke global condemnation.

Furthermore, India’s evolving foreign policy posture, marked by assertive diplomacy, regional leadership ambitions, and a desire to recalibrate its relationship with Pakistan, has created new incentives to revisit traditional mechanisms like the IWT. While strategic restraint has been the guiding principle in the past, there is now a growing debate within India’s strategic community on whether the treaty still serves India’s long-term national interest, especially in the face of cross-border terrorism, China–Pakistan strategic alignment, and water stress in Indian states like Jammu & Kashmir and Punjab. At the same time, Pakistan views any alteration in the status quo as a national security threat.

Water is not just an agricultural or economic resource for Pakistan it is a lifeline. Over 90% of Pakistan’s agricultural output depends on the Indus River system, and any disruption, even if technically legal under the treaty, is perceived as a form of aggression. This makes the IWT a sensitive and emotionally charged issue in Pakistan’s political and security apparatus.

Therefore, this paper seeks to critically explore the transformation of the Indus Waters Treaty from a symbol of peaceful cooperation into a strategic tool of geopolitical leverage. It aims to examine the underlying power dynamics that shape the treaty’s implementation, assess its role in India’s broader Pakistan policy, and analyse whether it can or should continue to function as a pillar of stability in South Asia. Through an interdisciplinary lens encompassing international law, strategic studies, water politics, and environmental diplomacy.

Literature Review

A Treaty at the Crossroads of History and Strategy

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), established in 1960, is widely recognised as a pivotal agreement in transboundary water management between India and Pakistan, two nations with a history of antagonism. Early scholarship, exemplified by John Briscoe (2009) (Briscoe, 2009) and Arun P. Elhance (1999), often lauded the IWT as a triumph of water diplomacy, highlighting its durability through conflicts and its role in conflict resolution through technical cooperation. Briscoe praised the treaty’s simplicity and neutrality for its longevity, while Elhance described it as a ‘textbook case of conflict resolution through technical diplomacy.’ However, this initial perspective often overlooked power asymmetries and potential strategic limitations for India, as well as Pakistan’s geostrategic vulnerabilities due to its dependence on Indian-controlled western rivers.

Following the Kargil conflict in 1999 and the 2001 Indian Parliament attack, a significant shift in academic focus emerged, interpreting the IWT not merely as a peace mechanism but as a potential instrument of strategic coercion. Mark Zeitoun and Jeroen Warner (2006) introduced the concept of ‘hydro-hegemony,’ which posits that upstream nations like India can exert control over transboundary river systems through various means, even without violating the treaty. While acknowledging India’s technical dominance, Ramaswamy Iyer (2011) cautioned against weaponising water, advocating for trust-building over coercion, yet noting the increasing perception of the IWT as a foreign policy tool in India.

Subsequent events, such as the 2016 Uri and 2019 Pulwama attacks, further intensified calls from Indian think tanks and policymakers like C. Raja Mohan (2020) and Ravi Ranjan (2019) to leverage India’s usage rights under the IWT as a ‘silent weapon’ for coercive diplomacy. Simultaneously, a counter-narrative emerged from scholars such as Salman M.A. Salman and Kishor Uprety (2003), along with Michael Kugelman (various works) (Kugelman, n.d.), who underscored the legal and ethical ramifications of weaponising water, emphasising the IWT’s international legitimacy and the potential for severe humanitarian consequences. Daanish Mustafa, Aasim Sajjad Akhtar, and others (Mustafa & Akhtar, n.d.) have extensively detailed the devastating human cost of water disruption, particularly for vulnerable communities.

More recently, researchers, including Ali Tauqeer Sheikh (2019) and Sadoff & Grey (2015) have highlighted the unaddressed challenges posed by climate change to the IWT’s framework, pointing to the need for updated agreements to account for altered water availability and dispute resolution mechanisms in the face of melting glaciers and erratic monsoons. This literature review reveals that the Indus Waters Treaty, once hailed purely as a model of cooperation, is now increasingly viewed through a strategic and political lens. While it continues to function effectively on a technical level, the growing pressures of national security, political hostility, and environmental uncertainty are pushing the treaty into uncharted territory.

The recent Pehalgam terrorist attack in April 2025 made it evident that water in the Indus Basin is no longer just a natural resource—it’s also a bargaining chip, a tool of statecraft, and a symbol of deeper unresolved issues between India and Pakistan. The academic conversation around the IWT is evolving, but it must also expand to address the challenges of our time. The current study hopes to contribute by providing a nuanced and balanced understanding of how the treaty fits into the broader puzzle of South Asian geopolitics.

Research Gaps

Lack of Strategic Analysis

While existing literature focuses largely on the technical, legal, and hydrological aspects of the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) (Briscoe, 2009; Elhance, 1999; Salman & Uprety, 2003), there is a significant gap in understanding its geostrategic dimension. Few scholars have critically examined how the treaty may be used by India as a tool of coercive diplomacy or soft power in its strategic rivalry with Pakistan (Zeitoun & Warner, 2006; Iyer, 2011; Mohan, 2020; Ranjan, 2019).

Most research treats the IWT as a bilateral treaty between two nations without studying its regional and sub-national impact, particularly in Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh, where the rivers originate or flow. Understanding the treaty’s impact on local politics, development, and inter-state water management is largely missing (Mustafa & Akhtar, n.d.; Kugelman, n.d.).

Insufficient Analysis on Treaty Limitations

While some suggest using the treaty as leverage, there is limited study on the legal limitations and risks India would face by altering or suspending it (Salman & Uprety, 2003; Iyer, 2011; Kugelman, n.d.). There is a gap in exploring the consequences under international law, World Bank involvement, and how such actions might backfire diplomatically or economically (Salman & Uprety, 2003; Sheikh, 2019; Sadoff & Grey, 2015).

Research Objectives

- To examine the Indus Water Treaty from a geopolitical and strategic viewpoint

- To assess the evolving context of India-Pakistan relations and how it impacts the treaty’s interpretation.

- To provide policy suggestions or strategic recommendations for future Indo–Pak water diplomacy

Research Questions

- To assess how India has used water control under the treaty as a diplomatic or strategic pressure point against Pakistan.

- To evaluate Pakistan’s responses and diplomatic strategies in maintaining the treaty and countering India’s posturing over water issues.

Research Methodology

This study will follow an analytical approach to move beyond technical interpretations and investigate how the IWT serves as a foreign policy instrument. It will use official documents along with secondary sources like academic studies and expert analyses. Its main focus will be on identifying IWT’s use (explicit or implicit) during times of military or diplomatic standoffs and evaluating its symbolic and real value as strategic leverage (Zeitoun & Warner, 2006; Iyer, 2011; Mohan, 2020; Ranjan, 2019).

Analysis

India’s strategic posturing concerning the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) following terrorist attacks in Pahalgam constitutes a sophisticated exercise in coercive diplomacy. Rather than pursuing outright abrogation, an action that would violate a solemn international agreement and invite severe legal and political repercussions, India employs a strategy of calculated signalling. This approach leverages the IWT’s framework as a non-kinetic instrument of statecraft to exert pressure on Pakistan.

India’s actions, which include suspending meetings of the Permanent Indus Commission and making public statements about ‘reviewing’ the treaty, are not intended as a genuine repudiation but as a psychological and diplomatic signal. This places the IWT’s long-term viability in question, directly targeting Pakistan’s perceived water security and creating a deterrent effect. The primary objective is to compel a change in Pakistan’s behaviour regarding cross-border terrorism without resorting to armed conflict. This strategy also serves India’s domestic interests by providing political space to accelerate the development of its own hydroelectric projects on the western rivers, projects that are technically permissible under the treaty but have been a source of bilateral friction.

As this research has explored, India’s upper-riparian position naturally gives it certain advantages within the treaty’s structure. While India has largely respected the terms of the agreement, recent political and security developments, including cross-border terrorism, the abrogation of Article 370, and shifting regional alliances, have led to growing discussions within India about the strategic potential of the IWT. Even without violating the treaty, India has legal and technical avenues to maximise its utilisation of the allocated waters, which could indirectly impact Pakistan’s water security. In contrast, for Pakistan, any reduction or disruption of water flows is viewed not just as a policy challenge but as an existential threat, given its extreme dependence on the Indus River system for agriculture, industry, and daily life.

Despite the perceived advantages, this strategy carries significant risks to India’s international reputation. Unilaterally sidelining a World Bank-brokered treaty, even temporarily, could be perceived as a violation of international law and a disregard for multilateral institutions. Such a move could lead to international condemnation and diplomatic isolation, potentially garnering international sympathy for Pakistan and its position. Moreover, this approach sets a dangerous precedent that could be used against India by upstream riparian states, most notably China, regarding transboundary rivers like the Brahmaputra. India’s pragmatic stance is thus a delicate balance; it seeks to exploit the treaty’s ambiguities and Pakistan’s dependency without compromising its own standing as a responsible power or escalating the conflict to a point of no return. By avoiding a full abrogation, India maintains the moral high ground and avoids a humanitarian crisis, thereby preserving its long-term strategic interests while still holding Pakistan accountable for its actions.

Conclusion

The Indus Waters Treaty stands out as one of the rare examples of a functioning agreement between India and Pakistan, even while most other aspects of their bilateral relationship remain tense and conflict-prone. For over six decades, the treaty has provided a framework for the sharing of vital water resources in the Indus River system, enabling both nations to utilise the rivers while preventing direct conflicts over water itself. However, beneath this facade of cooperation lies a more complicated and evolving reality, where the treaty has increasingly become intertwined with the larger geopolitical tensions between the two countries.

The broader international environment is also adding new layers of complexity. Climate change, shrinking Himalayan glaciers, changing monsoon patterns, and rising population pressures have made water an even more scarce and valuable resource. In such a scenario, the Indus Waters Treaty carries both the risk of becoming a future flashpoint and the hope of remaining a stabilising force if both nations can navigate their differences with maturity and foresight.

Ultimately, the Indus Waters Treaty represents more than just a technical water-sharing arrangement; it reflects the constant balancing act between cooperation and competition that defines India-Pakistan relations. Whether it continues to serve as a symbol of peace or gradually transforms into a tool of strategic leverage will depend largely on the political will, diplomatic skill, and mutual trust (or lack thereof) between both countries. In the years to come, the ability of India and Pakistan to manage this delicate balance will not only shape their bilateral ties but may also serve as a broader lesson for international water diplomacy in other conflict-prone regions of the world.

Title image courtesy: IASBaba

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies

References

Wolf, A. T. (1998). Conflict and cooperation along international waterways. Water Policy, 1(2), 251–265.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1366-7017(98)00019-1

Wolf, A. T. (1998). Conflict and cooperation along international waterways. Water Policy, 1(2), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1366-7017(98)00019-1

Mustafa, D. (2010). Hydropolitics in Pakistan’s Indus Basin. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2010/01/hydropolitics-pakistans-indus-basin

Briscoe, J. (2009). Troubled Waters: Can a Bridge Be Built over the Indus? Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Elhance, A. P. (1999). Hydro Politics in the Third World: Conflict and Cooperation in International River Basins. United States Institute of Peace Press.

Zeitoun, M., & Warner, J. (2006). Hydro-hegemony–A framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts. Water Policy, 8(5), 435–460.

Iyer, R. R. (2011). Indus Treaty: A Different View. Economic and Political Weekly, 46(45), 64–67. Legal Constraints and Moral Considerations: The Dilemmas of Weaponising Water

Salman, S. M. A., & Uprety, K. (2003). Conflict and Cooperation on South Asia’s International Rivers: A Legal Perspective. World Bank Publications. Legal and Humanitarian Dimensions: Should Water Ever Be Used as a Weapon?

Salman, S. M. A., & Uprety, K. (2003). Conflict and Cooperation on South Asia’s International Rivers: A Legal Perspective. World Bank Publications.

United Nations. (1997). Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses.

Akhtar, A. S. (2010). The Politics of Water in Pakistan. In Water Politics and Water Security in South Asia (pp. 125–142). Environmental Uncertainty and Climate Change: The Future Challenge

Sheikh, A. T. (2019). Climate Change and the Indus Waters Treaty: Warnings from the Himalayan Glaciers. Journal of Himalayan Studies, 5(2), 66–81.

Sadoff, C. W., & Grey, D. (2015). Water Security and Development: Analytical Framework. Water Policy, 17(S1), 146–158.

Singh, R. (2008). Trans-boundary water politics and conflicts in South Asia: towards ‘Water for Peace’. A report of Centre for Democracy and Social Action. New Delhi, India: Centre For Democracy And Social Action (CDSA).