Russia attacked Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Civilian casualties have surpassed 1800 numbers so far and the bombardments have forced nearly 10 million Ukrainians to escape across the border. The international community’s response has been immediate and concerted, with sanctions, armament transfers, and outspoken denunciation. China, on the other hand, has remained strikingly distinct. China’s envoy to the United Nations abstained from all voting to condemn the invasion, and Chinese media have avoided the term entirely. However, China’s leadership has long emphasised the inviolability of national sovereignty in its foreign policy, and Xi Jinping must strike a delicate balance in defending Vladimir Putin’s conduct.

What does Russia’s invasion of Ukraine mean for China? Where should one seek to have a better understanding of how China’s position on the conflict is likely to evolve?

However, over the last few days, Beijing’s position appears to be strengthening. China has remained a staunch supporter of Russia through its extensive strategic alliance and has opposed NATO expansion and sanctions against Russia. Simultaneously, it makes a show of adhering to its values of non-interference and constructive relations with Ukraine. In short, Beijing is attempting to bridge what many regards as an impenetrable gap.

Despite widespread condemnation of Russia, China appears to be siding with its northern neighbour, offering diplomatic cover at the United Nations and refusing to join sanctions against Moscow and the Russian elite. Such an approach is certain to re-intensify China’s ties with the United States and the European Union. Therefore, why has Beijing been so adamant about withdrawing from Moscow?

At least four possible justifications exist. To begin, given China’s tense relations with the United States and Europe, Beijing understands how critical it is to maintain Moscow on its good side. Beijing has designated the US as its major geopolitical opponent, and relations between the two countries are likely to remain difficult even if Xi Jinping withdraws his support for Vladimir Putin. It’s difficult to envision Xi personally supporting Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, as indicated by his pleas for Russia to negotiate with Ukraine during a phone chat with Russian President Vladimir Putin. However, Xi’s assessment, at least for the time being, is likely to be that it is preferable to maintain Putin as a partner, however difficult than to abandon him.

A second, related argument is that Beijing recognises Moscow’s economic impoverishment will provide it with cheap access to the Russian raw resources that power China’s industrial engine. Additionally, Beijing will exert unparalleled control over Russian economic matters.

Following that, China’s foreign policy establishment is almost certainly ecstatic that Russia is absorbing the lion’s share of American and European attention. Moscow’s detour, it is said, might provide China with further breathing room in the Indo-Pacific.

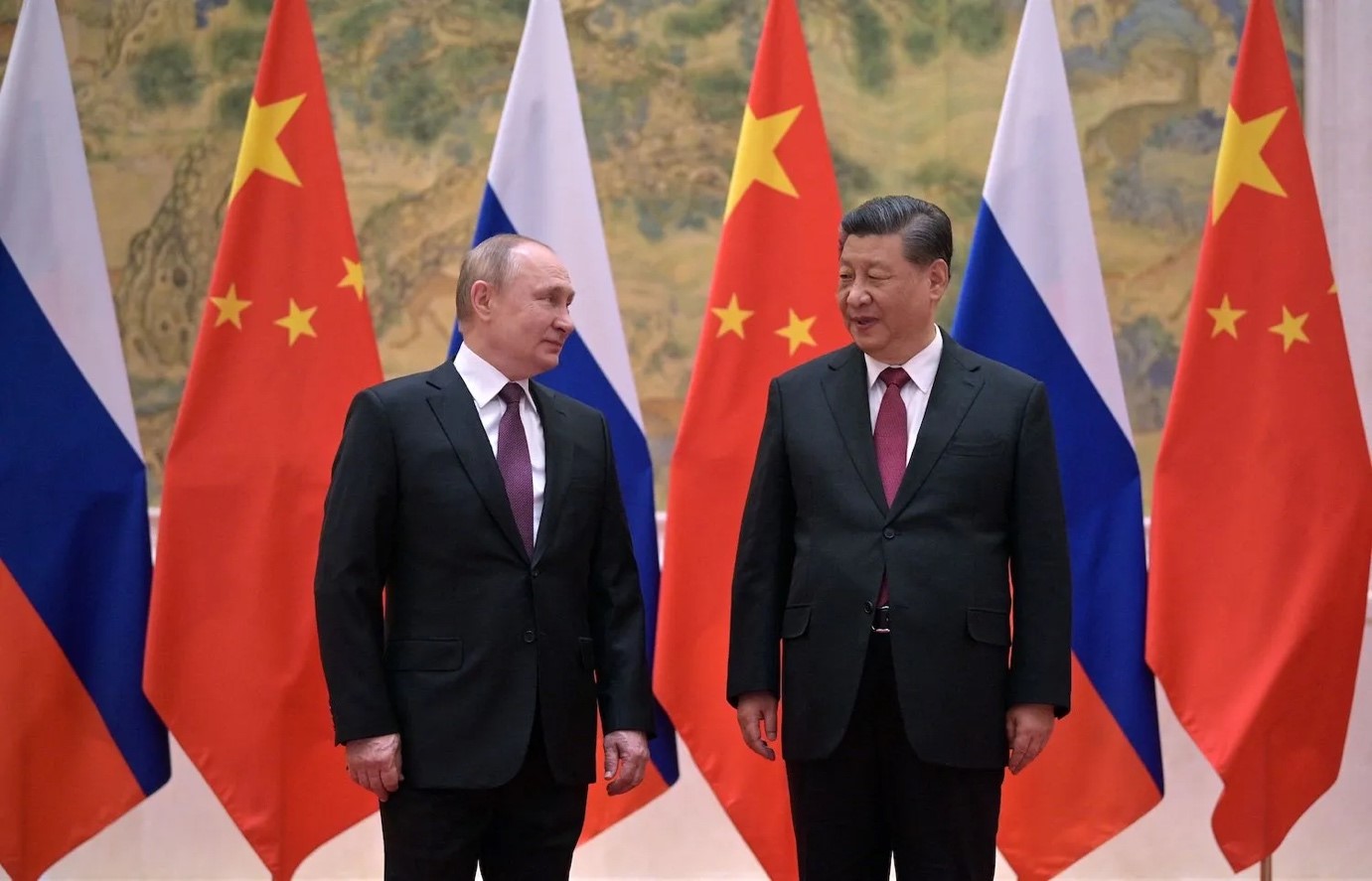

Finally, in recent years, the majority of Chinese researchers have emphasised the significance of Xi’s decision to develop a close personal relationship with Putin as a primary driver of improving China-Russia relations. Since 2013, the two men have met nearly 40 times, toasting birthdays, sharing caviar and shots of vodka, and forging a strong personal friendship in the process. This has given a strong signal to China’s bureaucracy that Xi supports attempts to strengthen China-Russia relations. As a result, anyone within the Chinese system is now politically vulnerable for suggesting that China examine the benefits of close strategic alignment with Russia. Such proposals could be interpreted as a direct criticism of Xi, as well as his connection with Putin, amid the extremely combustible political atmosphere preceding the 20th Party Congress. At this point, any big modifications in China’s current support for Russia are likely to require approval from the top.

Xi Jinping must now determine whether and how much assistance to provide to Russia’s economy and banking system when sanctions take effect. Beijing has traditionally rejected punishments based on domestic law, which it refers to as “long-arm jurisdiction.” China is expected to devise measures to assist Moscow in mitigating the sanctions’ impact without flagrantly breaking them. China’s playbook for assisting Iran and North Korea in evading sanctions outlines possible approaches. However, would this backing be sufficient to enable Russia to weather the sanctions’ consequences? Xi Jinping is unwilling to abandon his connection with Putin or China’s alliance with Moscow. According to Xi’s assessment of the international situation, the world is witnessing unprecedented transformations, including the decline of the United States and the collapse of Western democracies. The events of the last week are unlikely to have convinced Xi to substantially revise this opinion.

Nonetheless, Xi is unlikely to abandon his allegiance to Russia entirely. China’s foreign discourse will also reveal whether Xi is redoubling his support for Moscow or striving to reposition himself as more centrist. China’s words thus far indicate that Beijing is pretending neutrality but actually “leaning to one side,” blaming the US for the situation and redoubling its commitment to Russia.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies

Title image courtesy: Foreign Policy