Migrations have been taking place since the beginning of human evolution. Migration has both positive and negative consequences whether it is internal or international. What is the significance of India’s internal migration to its economy? What are the challenges to India’s national security caused by migration? The primary objective of this paper is to understand the challenges faced by migrants and the implications of migration in India. The paper takes the state of Kerala for a case study and analyses its different policies and approaches to migration within the state. The nature of migration and the reasons for such migration along with the question of whether the existing policies are adequate enough to address the growing problem of exploitation of migrants in India are looked into. A more holistic approach to migration and its challenges have also been addressed in detail. Revision of policy frameworks in order to minimise the negative aspects of migration is also addressed in brief. The paper draws from primary and secondary sources for its analysis.

Introduction and Background

The evolution of migration has been studied extensively by different scholars seeking answers to different questions. In India, the study of out-migration has always overshadowed the study of internal migration and its effect on the Indian economy. In this paper the basic objective is to address the challenges faced by migrants in India, the implications of migration in India along with the significance of migration to India’s economy. The inductive research approach has been used to address this paper with objectivity.

Ever since the dawn of time migration has happened not just in humans but in other species as well. “Migration is the mobility in a geographic landscape that involves a change in the area, it is a continuous process that has happened due to historical, economic, political or environmental reasons” (Ross, 1982). Migration can be divided into different categories such as inter, intra and international depending upon the movement in the geographical area.

Migrations are of two types, i.e., internal and external (international). Internal migration is the form of migration that happens within a nation and the different forms of internal migration are intra-district, inter-district and inter-state migration. When migration happens within the district boundary it is known as intra-district migration, while the migration from one district to another within the same state is known as inter-district migration and the migration from one state to another state is known as inter-state migration.

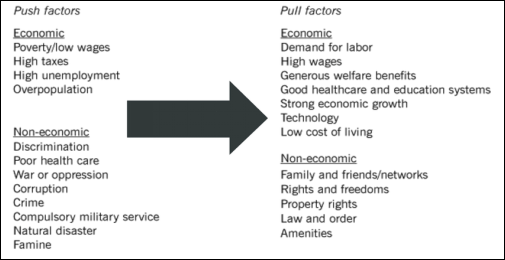

In contemporary times we have different ethnical, cultural and linguistic compositions due to migration. Different factors have triggered migration in humans over time, wars, environmental disasters, economic hardships and marriages constitute the majority of the reasons. Migration occurs both voluntarily and involuntarily. Voluntary migration may occur when an unskilled labour decides to move to another area from his local area based on the push and pull factors, the push factors could be unemployment or poverty and the pull factors could include the incentive to earn more for the same labour, especially in an urban environment. See Fig. 1 for some of the factors that prompt migration, this is quite different when compared to a person who is highly qualified and skilled moves to another region in his own country or to another country altogether; the chances of unskilled or uneducated persons being exploited when compared to their highly skilled or educated counter-parts are high. The primary reasons for involuntary or forced migrations are wars, corruption, ethnic conflicts, natural disasters, etc. The advancements and improvements in transportation, communication, demography, etc., have improved the ease of migration both internally and internationally.

Patterns of Migration in India

“Historically migration has not been that prevalent in the Indian subcontinent, the diversity in language and culture, traditional values, joint family system, dependence on agriculture etc. could be considered as some of the reasons” (Davis, 1951). It was only in 1981 that the Census Organisation which is a part of the Ministry of Home Affairs and in 1999-2000 the National Sample Survey which is a part of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, respectively added a questionnaire regarding the reasons for migration. Up until that point in time migration and its reasons were largely ignored by the officials even though a by-product of our partition during independence was migration. Migrations in India are of two types, long-term migration and short-term or seasonal/circular migration. The 2001 census report estimates the internal (both short and long-term) migrant numbers at 309 million while the 2011 census places it at 450 million (Census, 2011). The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd., 2023) reports that in 2020 alone there are 120 million seasonal migrants (Parishad, 2021).

The different patterns of migration can be classified as the following:

a. rural to rural,

b. rural to urban

c. urban to rural and

d. urban to urban

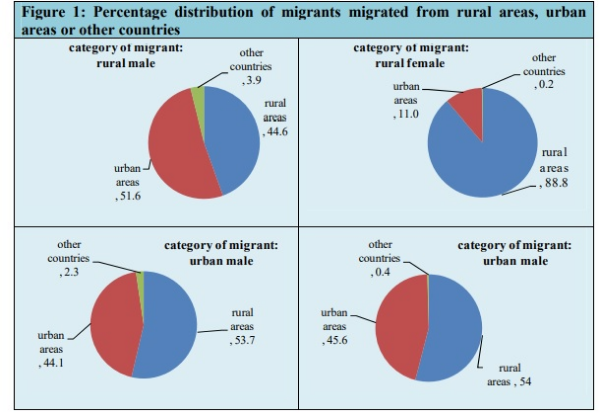

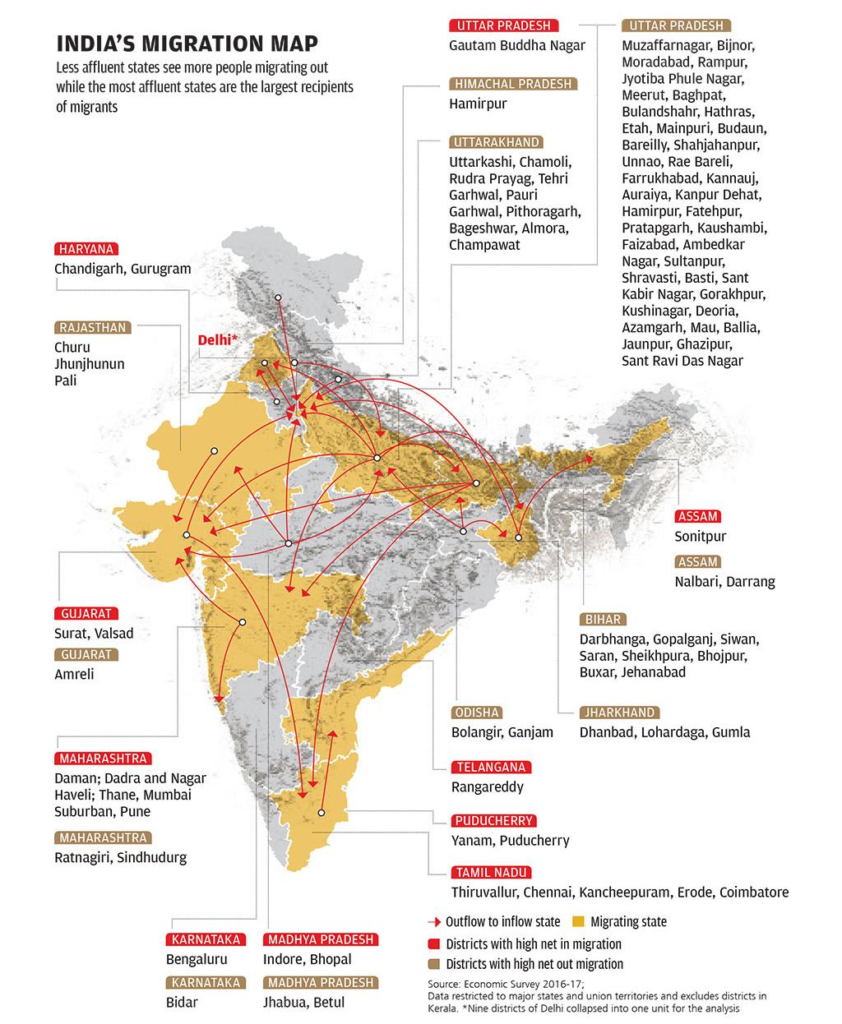

The 2011 census places almost 210 million rural to rural migrants which forms a whopping 54% of the total migration (Census, 2011). Fig.2 shows the distribution of different patterns of migration, the process of urbanisation saw an increase in the demand for labour and better wages attracted migrants which changed the rural-to-rural migration scenario to rural-to-urban migration. The flow of migration was mainly from the rural areas of the under-developed states to the urban areas of the developed states. The lack of better educational facilities also prompted people to migrate to urban areas. As per the report from the World Economic Forum in 2017, India’s in-migration is growing at a rate of 4.5 percent annually (Forum, 2017). The per capita income of a state not only influenced the in-migration but also the out-migration. States like Maharashtra, Delhi, Punjab and Gujarat attracted the highest number of in-migration while the state of Kerala which is the most developed state of India socially and educationally accounted for a large number of out-migrants especially to the West Asian countries (Zachariah, 2002). There were some fundamental differences in migrations between men and women, one of the main reasons why women migrated was marriage and for men, it was educational and economic reasons.

Challenges Faced by the Migrants

Migration is usually considered as an aspiration for many in different parts of the world but in India due to the socio-economic disparities, it is considered as a distress call (Parishad, Internal Migration in India and Experiences from High Out Migration States, 2021). The UNDP Human Development Report of 2009 states that the numbers of internal migrants in India are four times that of international migrants. One of the challenges that India as a country face is that of the seasonal or circular migrants, these are people who are migrating for temporary periods and may revert to their area of origin. The seasonal migrants in India are dominated by socially and economically marginalized communities (Keshri, 2013). There are ample surveys to state that these migrants are living in cramped slums and most have been excluded from most benefits especially in cities including access to social security programs (Chandrasekhar, 2019).

The Planning Commission of India (Twelfth Five Year Plan) also sees the rural-to-urban migration as a distress migration mainly due to poverty (Twelfth Five Year Plan, 2012-2017). The social exclusion faced by the migrants in different states is inhuman in different ways as the social exclusion not only includes discrimination based on gender, religion or region but also includes denying them equal opportunities, unfortunately, coercive inclusion does not do any good for either the society or the migrants. These discriminations are connected with migrants living in slums and having poor living conditions. The local governments could evict the slum dwellers without providing an alternate housing option and also without prior notice (Iyer, 2016). Proving the identity of the migrant state is another challenge for the migrants, as different states have different variations on how documents are issued. Opening a bank account also remains a challenge for many migrants because without adequate proof the Know Your Customer norms of the banks cannot be met and opening a bank account becomes a nightmare. Many migrants are politically excluded as some are unable to even vote in elections as many of them leave their place of origin at a very young age and in India the age to issue a voter ID card is eighteen. Long-distance migration and the delay in time for the issuance of ID cards are some other reasons why they are unable to obtain one even when they become eligible. The identity politics of local parties in different states have also marginalized migrants, an example of this would be the anti-migrant riot in Mumbai (Jazeera, 2008). The dichotomy here is both puzzling and challenging for the authorities when it comes to migrants and the discrimination they face, as these migrants are involved in many civil and criminal cases and they themselves create a notion and prejudice among the local population that the migrants are troublemakers and untrustworthy (Saikiran, 2021). It was again highlighted during a riot in Kochi, Kerala by the migrants against the local police (Philip, 2021).

A 2019 survey by the Indian Journal of Applied Research found that almost 29% of the workforce in India are migrants and out of that 95% of the surveyed personnel in Delhi, NCR region migrated for employment-related reasons. Almost 11% of the total migrants in India migrate due to the lack of employment opportunities or better employment opportunities (Bureau P. I., 2020). The conflicting factors emerge between the local population and migrants when these migrations affect the identities, cultures and ethnolinguistic characters prompting the local population to resort to violence and other measures due to their bias or fear. The fear of losing local employment opportunities to the migrants along with the negative sentiment that these migrants compete over limited available resources makes the perception even more negative towards them. The possibility of radicalization of migrants is a direct security concern of both the state and the central government (Nambiar, 2020). In December 2020, The Ministry of Labour and Employment introduced a Bill on the Code of Social Security, the Bill (Clause 113) talks about registering every unorganised worker by assigning a distinguishable number to his application or by linking the application to their Aadhaar number (Ravi, 2020) thereby curbing the concerns to national security (GOI, 2020).

Impacts and Implications of Internal Migration in India

Internal migration in India has both positive and negative impacts. The growth of the migrants directly and indirectly contributes to the growth of their home which in turn has a positive impact on the state and the nation. Internal migration also transforms and upgrades the skills of the migrants so preventing it might be counterproductive.

Positive Impacts

The first and foremost feature of internal migration from the economic aspect is that it prevents households from slipping into poverty and studies have proven that for certain societies in India, migration is the only way to move out of poverty due to their lack of education and other societal discriminations. Another important feature is that the migrants get access to formal banking channels, this ensures that the remittance made by them are legal and accounted for and this was effective and proven during the Covid-19 lockdown in India where there were restrictions on travel. The covid-19 lockdown had also shown that we need to have a holistic approach towards migrants and their welfare in order to avoid the mishaps that happened in the same period and to ensure that it does not get repeated in the future. Recently there is a feminization of migration as a large number of women and children have also been migrating due to economic reasons but these children prefer rural to rural migration (Census, 2011). The spatial earnings gap along with the difference in wages of pay and the probability of increased employment opportunities are the typical economic reasons behind migration in India.

Negative impacts

There are many states that discriminate against migrants which is not only unconstitutional but also bad politics. As per a report in Economic Times, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Karnataka have taken a discriminating stand against migrants (Aiyar, 2018). The lack of awareness and knowledge among migrants about their rights, the trafficking of young women and children under the pretext of migration along with sexual harassment (Bureau T. H., 2022) and workplace violence are some of the major negative impacts. Nutrient deficiency diseases along with communicable and other sexually transmitted diseases also impact negatively. The lack of identity among the migrants in the new society alienates them even further and the introduction of the Citizenship Amendment Act has created a false sense of fear making them susceptible to radicalization and other forms of anti-national elements (Abbas, 2015). The challenges in the development process of migration are the inclusion and integration of migrants as certain societies, especially in certain parts of India do not have a positive view towards migrants. The polarity indeed arises due to the wrongdoings and involvement of many migrants, both internal and external, in illegal activities in the state to which they have migrated, especially the rise of illegal migrants from Myanmar, Bangladesh, Nepal etc. (Jain). Discrimination usually doesn’t exist among the local population but when an illegal migrant from any other country is arrested or flagged as dangerous it transmits fear to the locals about the internal migrants as well.

The integration of migrants is also costing exchequers, as new schemes and policies have to be rolled out which in a way creates a financial burden on the governments. In the wake of the aftermath of the Covid-19 ruckus of the migrants, the central government announced several relief packages and the most important among them was the 300 billion dollar package announced on 16th May 2020. The question of defence versus development is always a gun versus butter question, whether these packages could have been better suited to strengthen and develop India’s national security owing to the geopolitical position of the country or whether these welfare schemes do bring about a change in the life of these migrants’ remains a question of debate. By marginalizing the migrants, they are being denied some of basic human rights such as:

- The right to work and receive wages that contribute to an adequate standard of living

- The right to freedom from discrimination based on origin, caste, creed, religion etc.

- The right to equality and equal protection before the law.

- The right to freedom from forced labour.

- The right to safe working conditions.

- The right to freedom from sexual harassment in the workplace.

- The right of education to migrant children.

The Security Impact of Migration in Kerala – Case Study

Kerala is a state which suffers from both brain drain and labour shortage due to the migration that happens in the state (Rajan, 2020). This has prompted migration to Kerala from other parts of the country the districts which have the highest number of migrants in Kerala are Ernakulam, Thrissur and Alleppey respectively and the construction sector has the highest number of migrant workers in the state followed by manufacturing and agricultural sectors (Kerala State Planning Board, 2021). Emigration on a large scale and an ageing population has paved the way for an increase in the number of migrants in the state (Kerala State Planning Board, 2021). On average, it is estimated that 81% of the total migrant children in Kerala are attending regular schools and there are ample policies to address the grievances of the migrants and their families, in spite of all these policies and measures high crime rates among the migrants is still a concern for the state (Kerala State Planning Board, 2021). The Chief Minister of Kerala had officially stated that around 3650 criminal cases had been registered against migrant workers in Kerala in the last 5 years and Ernakulam has the highest migrant crime rates among all states in Kerala (Mathrubhumi, 2021). Another concerning report emerged when it was reported that almost 56% of the migrant workers in Kerala have major diseases (Kallungal, 2021). The crimes are committed not only against the natives but also against their own families and communities as evidenced by the conviction of a migrant from West Bengal by the Kerala High Court against his own partner (Varghese, 2021). The state of Kerala has taken many steps to ensure that the rights of migrants are protected and safeguarded by both the state legislature and the judicial authorities. A public interest litigation initiated by the Kerala High Court ‘Jana Samparka Samithy’ against the State of Kerala is such an example of how much the migrants are valued and protected in the state (Jana Samparka Samithy, 2020).

Significance of Migration on the Indian Economy

The average wage per day for a job in the agricultural sector is around Rs. 291 per day while a casual salaried job provides around Rs. 551 per day (Vyas, 2021). With effect from the 1st of October 2022, the minimum wage to be paid to an unskilled worker in the agriculture sector for ‘A’ category cities is Rs. 454, ‘B’ category cities are Rs. 414 and ‘C’ category cities are around Rs. 409 (Commissioner, 2022). The low wage in the agricultural sector and the obvious underpay have prompted unskilled labourers to migrate to areas where they could come out of poverty which in itself is a distress signal. Even though there is a linear relationship between economic developments and migration, the economic exploitation of these unskilled and semi-skilled labourers is not measured quantitatively. The exploitation of the migrants by not paying the minimum wage becomes a hindrance in catering to their basic needs as well as achieving their dream of economic prosperity. This in turn increases the burden on the government as they have to undertake new social support, unemployment and healthcare schemes. The low pay and substandard lifestyle prompt the migrants to resort to other illegal means like drug trafficking, as reports prove that many migrant workers are under observation (Joseph, 2022).In the Fiscal year of 2022, India’s total inward remittance was around Rs. 6.83 lakh crores which was roughly 3.5 percentage of the entire GDP of the country (Verma, 2022). Taking the classic example of the state of Kerala alone, the remittances, especially from the West Asian countries, provide ample support to the economy of Kerala which if otherwise could have plunged the state into poverty. The lack of employment opportunities in Kerala is due to unionism, red tape delay and the lack of labour work culture among themselves. As per the RBI report of 2018 Kerala alone accounts for 19% of the total remittances made in India (RBI). 17 percent to 18 percent of Kerala’s workforce which accounts for almost six percent of the entire population are estimated to be emigrants (Kannan, 2020). The net state domestic product remittance to the state of Kerala from the migrants during the 2015-2020 period is estimated to be around Rs. 90,468 crores (Kannan, 2020).

Policies to Address the Exploitation of Migrants in India

There is no denying the fact that there are many positive and negative implications to migration in India but there are only marginal numbers of policies and frameworks to address the exploitation of migrants. The response from the administration to most migration challenges is limited to restricting migration rather than addressing the core challenges. The lack of awareness and understanding of migration is one of the main reasons for such hasty and futile decisions. As per the Indian constitution, labour falls under the concurrent list so both the central and the state governments coming forward together would address the inequalities within the system to a certain level. The social inclusion of the migrants must be one of the top priorities of the government. The World Bank Group research in 2017 highlights that one of the most powerful barriers in India to interstate migration is the administrative barrier (Zovanga L. Kone, 2017). The constitution of India guarantees its citizens six fundamental rights. They are the Right to Equality, Right to Freedom, Right against Exploitation, Right to Freedom of Religion, Cultural and Educational Rights and the Right to Constitutional Remedies (GOI, 1947). These rights are ensured for the betterment of the individuals as well as the society, so curtailing or limiting such guarantees and rights can hamper individuals especially the migrants who are trying to get a better life. Certain Central government schemes and policies have been addressed and as a case study, Kerala state government policies are looked into.

Central Government Policies

There are 44 labour laws in India under four categories, but the only report that addressed both permanent and circular or seasonal migration was the Working Group on Migration Report (Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, 2017) and this report had the analysis of the three major dimensions of internal migration, i.e. location of the migrants in labour market structure, the issue of social service and protection and the issue of housing. A recent report by the International Labour Organization, Aajeevika Bureau and the Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development urged the Government of India to formulate a framework of policies to reduce the vulnerabilities of internal migrants in India. Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana is a skill-based initiative formulated for the migrant workforce but its penetration and implementation is at a slow pace. Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979 (Ministry of Labour & Employment, 1979) is applicable to contractors and establishments employing five or more five inter-state employees. Most of these labour laws address safety and employment opportunities but none of them addresses or even enables the minimum wage code which is linked to the basic standard of living. The inflow of Bangladeshi migrants to different parts of India under the pretext of being Indian has created some security checks for the Government of India (Kumar). As Central government policies and schemes alone cannot address the inequalities of migrants in India, the states could also formulate laws that are beneficial to both the employer and the employee.

State Government Policy: Kerala

The state of Kerala provides a paradox in itself. Most of the educated people in Kerala migrate to other nations especially West Asia while most of the workforce in Kerala is from other states. The migration of the people from Kerala to the Gulf Co-operation Council States started in the early 1970s. The boom in migrants from Kerala to West Asian countries was called the Kerala Gulf boom. This created a vacuum in the workforce which had to be filled by the migrants from other states not only due to the lack of labours but also due to the demand for unusually high wages from the existing labours. Some of the positive impacts of migration in Kerala are that it alleviates poverty, and provides ample economic support and capital investments. Some of the negative impacts are the emotional distress that happens due to separation from families and losing human and labour capital to foreign markets. The immigrants especially to the West Asian countries automatically are sought to fill jobs that have unpleasant and hazardous working conditions.

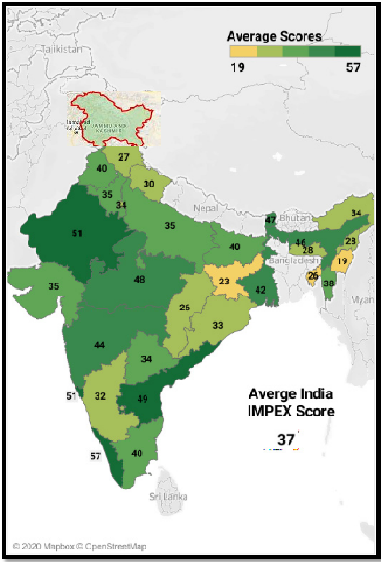

The free flow of migrants to Kerala along with the other routes to the south from the north-east of India started with the direct train, the Dibrugarh – Kanyakumari Vivek Express in 2011. In 2013, M P Joseph, a retired IAS officer and advisor to the Kerala government at that time on labour affairs, helmed a study ‘Domestic Migrant Labour in Kerala’ that pegged the annual number of domestic migrants newly arriving in the state for work at 2, 35,000 (Kashyap, 2016). Some measures to protect the migration population have been taken by certain states in India. Kerala is the first state in India to decree a social security scheme for migrant workers. The Interstate Migrant Workers Welfare Scheme was started in 2010 by the Kerala Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board for the welfare of the migrants. This scheme covers accidental medical and accidental death insurance, children’s education allowance and terminal benefits. The government is also partnering with Bhavanam, a nonprofit public sector company, to provide hostel facilities for migrant workers. The state government along with different NGOs have prioritized safe migration, especially for vulnerable women. Fig. 4 shows the inter-state migration policy index of different states and it shows that the state of Kerala tops the Interstate Migrant Policy Index (IMPEX) of 2019 (Cloud, 2020), IMPEX measures the integration of migrants in the states. The project Roshni was also developed to recognize the special need of migrant children in terms of healthcare, education and protection. The state of Kerala in order to address not only the basic necessities of the migrants but also other vulnerable groups had announced a package worth Rupees 200 billion which was applauded by several other nations (Bhagat and Rajan, 2021). The migration to Kerala has become more permanent as the migrants are settling in the state with ease (Aggarwal, 2020).

Conclusion

The difference between migrants and refugees is evident in the rights granted by the Government of India through the Constitution to the migrants. Migrants cannot be discriminated against based on their caste, creed, religion, language etc. Migrants have equal rights just like every other citizen of this nation. Migration has helped people to slip away from poverty and hardships and to lead a decent lifestyle. The improvements in knowledge and understanding along with access to safe banking channels are a positive factor of internal migration, but there are numerous negative aspects too. The numerous negative impacts are exploitation of women and children, drug trafficking, diseases etc. under the pretext of migration. The trouble seems to rise when the migrant workers start exploiting their rights provided by the constitution. While the impact of internal migration on national security is undeniably a worrisome factor, the serious underpaying and financial exploitation of migrants is creating a serious brain drain for the country. Along with that, there is also a shortage of qualified workers in the country which is being utilized by other countries. A classic example would be the utilization of the Indian workforce in the West Asian countries. The involvement of migrants in illegal activities and crime syndicates is creating a big challenge for law enforcement agencies all across the country as evidenced by many reports that the Government of India is closely watching both internal and external migration (MHA, GOI, 2010). The solutions to these problems are not that simple and have repercussions at all levels. The central and state government could formulate policies and strategies that could benefit everyone involved and transparency is key to this. The discrimination against migrants could be minimized with grass root level awareness and education. Furthermore, adequate policies and development schemes could be studied properly and based on that assistance could be provided to areas wherever it is required. The labour legislation, especially the minimum wages act could be enacted with more strictness but it should be simplified wherever necessary. The current pace of development will only increase migration, especially to urban areas in India, the challenge for the policymakers is to develop policies that are not only linked to employment but also to the welfare of their families as well. The role of panchayats in registering workers and their welfare could be strengthened by an act of law. These solutions would further increase the central and state government expenditure whether it is spent on human resources or other resources, but it is the need of the hour and the long-term benefits would outweigh the short-term challenges. Improvements in governance, rural area developments, and institutions to prevent the exploitation of illiterate and socially backward people should be emphasized and implemented from micro levels; a bottom-up approach along with a top-down approach is needed as well if we are to ensure that the policies are effectively implemented. The tight monitoring regulation of each and every migrant by the government is practically impossible, time-consuming and resource-draining. Most of the migrants are just common people who are trying to have a better life with their limited skills and knowledge, while others may not, so generalizing them on a societal basis is constitutionally and morally wrong. Society has evolved and the time of large-scale nomadism is not so prevalent but as Mac Iver said, society is a web of social relationships and so it is quite difficult to detach migration from society (ASA, 1970). We must understand that governments alone cannot fulfil the needs of society and for that to achieve we need to come and move forward together.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies. The views expressed by the author are purely personal.

Title image courtesy: iPleaders

References

Abbas, R. (2015). Internal migration and citizenship in India. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 42 (1), 150-168.

Aggarwal, V. S. (2020, 03 09). The Integration of Interstate Migrants in India: A 7 State Policy Evaluation. International Migration , 144-163.

Aiyar, S. A. (2018, 12 23). Discriminating against migrants isn’t just unconstitutional, it’s also bad politics. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from The Economic Times: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/view-discriminating-against-migrants-isnt-just-unconstitutional-its-also-bad-politics/articleshow/67214561.cms?from=mdr

ASA. (1970, 06 15). Robert Morrison MacIver. Retrieved from asanet.org: https://www.asanet.org/about/governance-and-leadership/council/presidents/robert-m-maciver#:~:text=MacIver%20believed%20in%20the%20compatibility,democracy%20and%20multi%2Dgroup%20coexistence.

Bhagat and Rajan, I. S. (2021, 12 02). Internal Migration and Covid-19 pandemic in India. Retrieved 09 13, 2022, from sprinkler link: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-81210-2_12

Bureau, P. I. (2020). Migration in India. New Delhi: Government of India.

Bureau, T. H. (2022, 09 24). Migrant workers arrested on charge of sexually exploiting minor girl in Kozhikode. Kozhikode, Kerala, India: The Hindu. Retrieved 10 04, 2022, from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/migrant-workers-arrested-on-charge-of-sexually-exploiting-minor-girl-in-kozhikode/article65930726.ece?homepage=true

Census. (2011). Women and Migration In India. Ministry of Home Affairs. New Delhi: Office of the registrar general & census commisioner.

Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd. (2023, 03 14). Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd. Retrieved from CMIE: https://www.cmie.com/

Chandrasekhar, S. a. (2019). Migration, Caste and Livelihood: Evidence from Indian City-Slums. Urban , 12 (2), pp. 156-172.

Cloud, A. (2020, 11 10). IMPEX 2019 released by India Migration. Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Retrieved 01 13, 2023, from https://affairscloud.com/interstate-migrant-policy-index-impex-2019-released-by-india-migration-now-kerala-top/

Commissioner, O. o. (2022, 09 28). Chief Labour Commissioner. Retrieved 10 03, 2022, from Ministry of Labour and Employment: https://clc.gov.in/clc/node/706

Davis, K. (1951). The Population of India and Pakistan. The Milbank memorial fund quarterly , 188-192.

Encylopaedia Britannica

Forum, W. E. (2017). Migration and its Impact on Cities. Cologny: World Economic Forum.

Free Press Journal. (2023). 2.25 lakh people gave up Indian citizenship in 2022: Govt data. New Delhi: MSN.

GOI. (1947). The Constitution of India. New Delhi: GOI.

GOI. (2020). The Gazette of India. New Delhi: Ministry if Law and Justice.

Government of India, Planning Commission. (2012-2017). Twelfth Five Year Plan. New Delhi: GOI.

Iyer, D. S. (2016, 06 30). Innovative Strategies and Initiatives for the Social Inclusion of Internal Migrants in India. Global Journal of Advanced Research , 3 (6), pp. 533-540.

Jain, B. (2021, July 20). Illegal Rohingya immigrants pose threat to national security, says government. New Delhi, New Delhi, India. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/illegal-rohingya-immigrants-pose-threat-to-national-security-says-government/articleshow/84594622.cms

Jana Samparka Samithy, WP(C).No.23724 OF 2016 (Kerala High Court July 01, 2020).

Jazeera, A. (2008, 02 18). Arrests in India migrant row. Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Retrieved 10 04, 2022, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2008/2/18/arrests-in-india-migrant-row

Joseph, A. M. (2022). Migrant workers under scanner for suspected drug trafficking. Kozhikode: The Hindu.

Kallungal, D. (2021). 55.6% migrant workers in Kerala have major diseases: Study. Thiruvananthapuram: The New Indian Express.

kannan, K. (2020). Revisiting Kerala’s Gulf Connection: Half a Century of Emigration, Remittances and Their Macroeconomic Impact, 1972–2020. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics , 941-967.

Kashyap, S. G. (2016, 08 15). The Big Shift: New Migrant, new track. Retrieved 08 17, 2022, from The Indian Express: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/the-big-shift-new-migrant-workers-new-track-2975656/

Kerala State Planning Board. (2021). A study of in migration, informal employment and urbanisation in Kerala. Evaluation Division. Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Kerala.

Keshri, K. a. (2013). Socioeconomic Determinants of Temporary Labour Migration in India: A Regional Analysis. Asian Population Studies , 9 (2), pp. 175-195.

Kumar, A. (2011). Illegal Bangladeshi Migration to India: Impact on Internal Security. Strategic Analysis , 35 (1), 106-119.

Mathrubhumi . (2021). 3,650 criminal cases filed against migrant workers in last 5 years in Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram: Mathrubhumi newspaper.

MHA, GOI. (2010). Ministry of Home Affairs Annual Report 2009-10. New Delhi: MHA.

Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation. (2017). Report of the Working Group on Migration. New Delhi: GOI.

Ministry of Labour & Employment. (1979, 06 11). Inter-State Migrant Workmen. Retrieved 01 13, 2023, from Chief Central Labour Commissioner: https://clc.gov.in/clc/acts-rules/inter-state-migrant-workmen

Nambiar, A. (2020, 04 07). Centre for Land Warfare Studies. Retrieved 09 13, 2022, from www.claws.in: https://www.claws.in/migration-and-national-security/

Parishad, E. (2021). Internal Migration in India and Experiences from High Out Migration States. Migration Policy paper , 01-32.

Parishad, E. (2021). Internal Migration in India and Experiences from High Out Migration States. Migration: Policy Paper 2021/WHH , 1-32.

Philip, S. (2021, December 27). Kerala: 50 migrant workers arrested for attack on police in Kochi. Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/thiruvananthapuram/kerala-50-migrant-workers-arrested-for-attack-on-police-in-kochi-7692186/

Rajan, S. I. (2020). India Migration Report 2020. London: Routlege India.

Ravi, S. (2020). Vulnerable Internal Migrants in India and Portability of Social Security and Entitlements. Delhi: Institute for Human Development.

RBI. (2018). Globalising People: India’s Inward Remittances. New Delhi: RBI.

Rees, P. (2020). Internal Migration Measures and Trends. In P. Rees, International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (pp. 73-77). Kingston: Elsevier.

Ross, J. A. (1982). Human migration: concepts and approaches. Concepts and meanings of migration , 448-449.

Saikiran, K. (2021, December 27). Migrant trouble: 3,650 cases in five years in Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. Retrieved Novemeber 25, 2022, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/thiruvananthapuram/migrant-trouble-3650-cases-in-five-yrs/articleshow/88511037.cms

Varghese, M. H. (2021). Plight Of Migrant Workers An Endless, Sad Narrative: Kerala High Court While Upholding Bengal Native’s Conviction For Partner’s Murder. Thiruvananthapuram: LiveLaw.in.

Verma, M. (2022, 07 22). The US economy’s recovery from covid helped boost remittances to India. Retrieved 10 06, 2022, from Quartz India: https://qz.com/india/2191298/the-us-has-surpassed-uae-as-the-top-remittance-source-for-india/#:~:text=In%20fiscal%202022%2C%20India’s%20total,pdf)%20published%20on%20July%2016.

Vyas, M. (2021, 08 09). Migration from factories to farms. Retrieved 10 03, 2022, from Centre for monitoring Indian Economy: https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=20210809122441&msec=850

Zachariah, K. K. (2002). Kerala’s Gulf Connection. In K. K. Zachariah, Kerala’s Gulf Connection: CDS studies on International labour migration form Kerala state in India (p. 244). Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, 2002.

Zovanga L. Kone, M. Y. (2017). Internal Borders and Migration in India. India: World Bank Group.

Mishra, K.D. 2016. Internal Migration in Contemporary India (pp., 181-185). The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, Sage Publications, New Delhi.

Mahapatro, S.R. 2010. The changing pattern of Internal Migration in India. Institute of social and economic change, Bangalore.

Remesh, P.B. & Agarwal, T. 2020. Changing contours of internal migration in India. Manpower Journal, Vol. LIV, No. 3 & 4.

Srivastava, R. 2011. Internal Migration in India. Indian Council of Social science research, New Delhi.

Bhagat, R.B. 2010. Internal Migration in India: Are the Underprivileged Migrating more? (pp. 27-43). Asia-Pacific Population journal, Vol. 25, No.1.

Bhagat, R.B. &Keshri. K. 2020. Internal Migration in India. Internal Migration in the countries of Asia (pp. 207-228).

Rajan, S.I. &Bhagat, R. B. 2021. Internal Migration in India: Integrating Migration with development and urbanization policies. Policy Brief, issue 12.

Srivastava, R. &Keshri, K. &Padhi, B. &Jha, K.A. 2020. The impact of uneven regional development and demographic transition across states. www.ihdindia.org.

Iyer, M. 2020. Migration in India and the impact of lockdown on migrants. PRS Legislative Research Blog. https://prsindia.org/theprsblog/migration-in-india-and-the-impact-of-the-lockdown-on-migrants.

Kavitha, P &Valliamai, A. 2020. Economic Analysis of Internal labour Migration in India. International Journal of management, Vol. 11, issue 12.