The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a multibillion-dollar economic corridor that will connect China’s northwestern region of Xinjiang to the Pakistani port city of Gwadar. CPEC highlights China’s long-term geopolitical ambitions in South Asia and the Indian Ocean. However, the pace of this initiative has been hindered since its commencement due to the economic downturn, political instability, religious extremism, and terrorism that have gripped Pakistan. Nonetheless, the CPEC has significant security and geopolitical ramifications for India. Issues like India’s territorial integrity and militarization of the region and China’s naval buildup in the Indian Ocean pose serious challenges to geopolitical interests in the region. In the first section, this paper attempts to analyze the much-anticipated role of Pakistan as a reliable partner in the fulfilment of China’s geoeconomic and geopolitical plans behind CPEC. Secondly, this paper will examine and discuss the implications of CPEC on India, especially the security implications. This analytical paper relies on data from secondary sources such as journal articles, research papers and newspaper articles.

Introduction

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a transcontinental development project that aims to strengthen the global economy by boosting regional connectivity and trade. More than 1700 projects totalling $1 trillion are being implemented under the BRI umbrella, including transportations, power grids, energy storage and distribution systems, and so on. BRI is crucial to China because it expands the market for Chinese goods while cutting the cost of export and import. Marshall W. Meyer argued that BRI is vital to China because it is China’s global brand (Meyer & Zhao, 2019). Furthermore, this is a return-oriented Chinese investment. As a result, it must demonstrate some level of success, and any slowdown might be detrimental to Chinese strategic and economic interests.

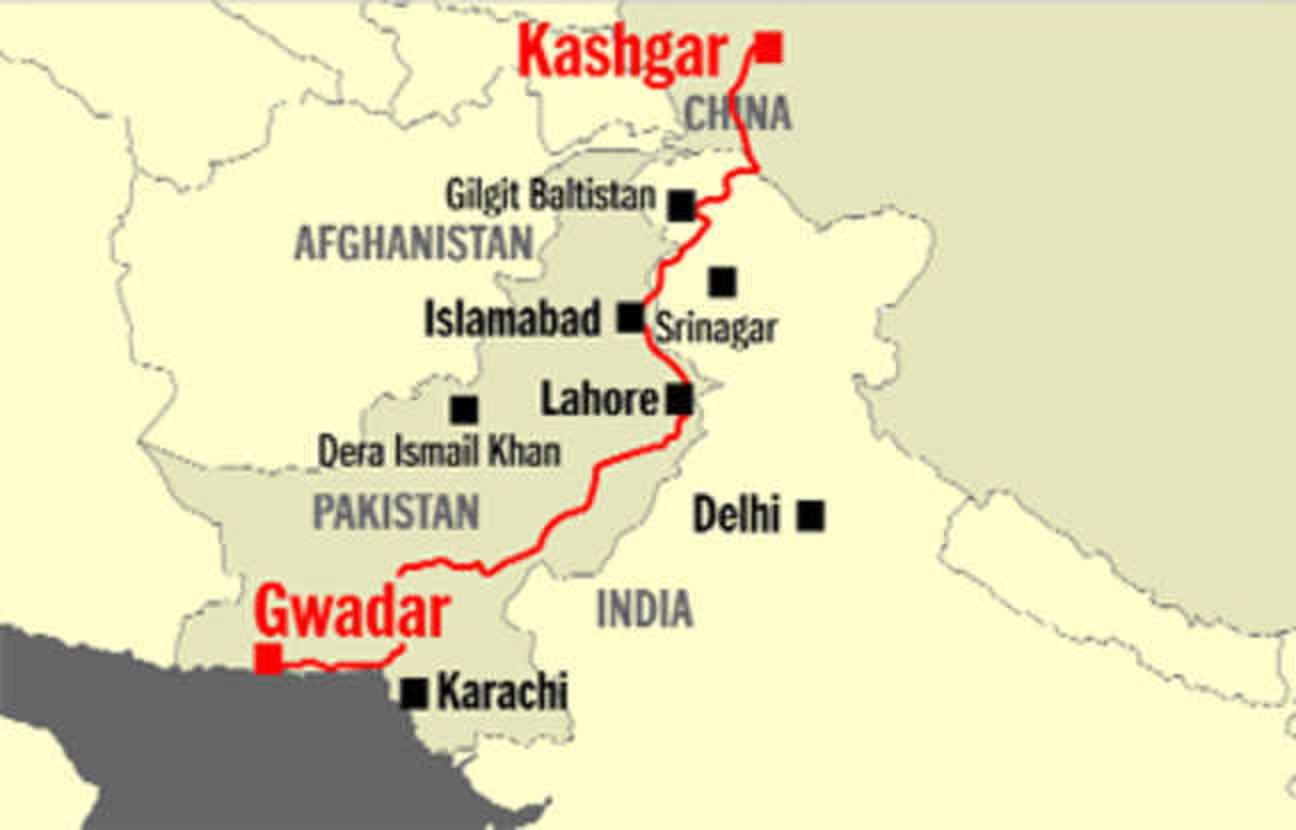

And what is critical for the success of BRI is the presence of robust institutions backing the initiative in host countries. Some BRI initiatives are located in difficult geographical and institutional settings. The $62 million China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which connects China’s BRI land and maritime components, is one of these initiatives. Compared to other projects, China has signalled that CPEC is a priority because it provides China with a direct connection to the Strait of Hormuz and the Arabian Sea. Geographically, CPEC moves from Xinjiang province of China and connects Kashgar with Pakistan at Khunjerab pass. From this mountain saddle by moving along the whole Pakistan territory, China expects to reach the Gwadar port, an entrance to the Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea, and the Persian Gulf. The CPEC is also a major cornerstone in China–Pakistan strategic partnership. This project holds great promise for both China and Pakistan, since it will help both countries economically, politically, and strategically, particularly China. First, the CPEC is predicted to reduce China’s trade transportation costs by 50%. Second, it will provide China with direct access to countries in West Asia, Central Asia, and Africa. Third, it will aid China’s counter-offensive against India in the Indian Ocean region.

The CPEC is expected to link China’s Kashgar and Pakistan’s Gwadar port. A large chunk of the CPEC will run the length of Pakistan’s territory. Given the importance of CPEC to China, the question of whether Pakistan can be a trusted partner in China’s Grand Initiative arises. Pakistan is a country that lacks a stable political order and is plagued by corruption and the military’s monopoly. The majority of the areas through which the CPEC passes, such as Gilgit-Baltistan and Balochistan, are infected with secessionism and terrorism. The fragile and difficult topography, including snow-capped peaks and the ecologically volatile region of Gilgit-Baltistan, are stumbling blocks in the completion of CPEC. Pakistan is already a bankrupt state, so no return can be expected and even the principal amount is at risk. All of these factors have already hampered the progress of numerous CPEC projects.

Nevertheless, the CPEC has serious strategic and security implications for India (Rahman et al., 2021). If CPEC proves a success, India will have to face strategic, security, and economic threats. First, India’s claim over PoK and Gilgit Baltistan will be weakened in the international arena. Second, the PLA will continue to intrude eastern Ladakh in order to secure this crucial CPEC project (Lal, 2020). Third, the increasing concentration of PLA forces in Pakistan is posing a security threat to India’s western borders. Fourth, CPEC will enable China to expand its naval presence and geostrategic stake in the Indian Ocean. This would put India’s regional diplomatic and military capabilities to the test. The focus of this paper will be on two major questions. First and foremost, can Pakistan be regarded as a credible partner in the CPEC’s implementation? Second, if CPEC becomes effective, what will be the major implications for India? To begin with, the importance of CPEC to China will be briefly examined.

Literature Review

Sering H. Senge (Senge, 2012) argued that China has started a strategic partnership with Pakistan just to use Pakistan as a security front and a low-cost but high-efficiency deterrent against the growing political and economic influence of India in the region. The expansion of the Karakoram corridor will impact the strategic interests of India. This will help Pakistan and China strengthen their military bases near the LOC and allow their armies to infiltrate into Ladakh and the Kashmir Valley swiftly and deeply. By developing this corridor, the Chinese are attempting to encircle India from its northern border. The continuous presence of Chinese workers in Pakistan along India’s western border is another challenge. China wants to divert India’s attention towards this region and keep itself engaged in yet another strategic front that is the maritime sphere.

Although CPEC is projected to benefit not just China and Pakistan, but also the surrounding areas. And deteriorating law and order circumstances in Balochistan and FATA, as well as the separatist movement in Gilgit Baltistan and Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan, religious extremism, and political instability, have continually overshadowed the benefits it is expected to provide. Therefore, its success depends on whether Pakistan will deal with those hurdles (Hussain, 2016).

Jeremy Garlick (Garlick, 2018) argues that Chinese investment in CPEC pipelines is less likely to go ahead due to economic, logistical, geographical, and security-related problems. And China’s motivation for developing infrastructure in Pakistan is to offset India’s regional dominance in the Indian Ocean Region. The Chinese interest in Gwadar and other IOR ports derives largely out of a geo-positional balancing against India.

The Politico-economic situation in Pakistan has sabotaged the progress of CPEC. Despite corruption accusations, the military establishment continued to increase its hold on matters pertaining to the Pakistani economy. Moreover, most of the coal-based projects stalled because of the rising debt and cost of coal, and the transport projects are suffering because of viability issues. The CPEC is affected due to an ongoing insurgency in Balochistan and to a lesser extent in the Gilgit Baltistan region. The impact of the Pakistan financial crisis on CPEC can be guessed from the reduced public sector development project budget for CPEC projects. The allocation was dropped to $130 mn USD for 2020-21 from $1.25 bn USD in 2018-19 (Joshi, 2021).

Pakistani Army’s dominance in the polity as well as over the economy of Pakistan entails a number of complications for Chinese economic interests that can affect the future of China’s CPEC investments and their financial sustainability. However, a number of issues have stymied the CPEC, including escalating prices, which are exacerbated in part by the expenditures of securitizing the CPEC. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s economy is not growing sufficiently to cover its huge debt obligations. And if the Pakistani economy continues to underperform, Chinese banks may be forced to cover the expenses of the CPEC (Boon and Ong, 2020).

Anshuman Rahul (Rahul, 2018) argued that China through CPEC wants to encircle India by having access to ports of neighbouring countries like Gwadar in Pakistan and Hambantota in Sri Lanka. The recent acquisition of a military base in Djibouti along with the transforming of a number of rocks, reefs, and atolls in the South China Sea into military bases do signify the Chinese geopolitical ambitions. Although as a response India has announced various connectivity projects in South Asia and beyond, but from a strategic perspective the key project would be the development of Andaman and Nicobar Islands as a maritime hub in the Bay of Bengal.

Sayantan Halder (Halder, 2015) has argued that the promises done by China’s BRI have largely been rhetorical without a proper road map. In fact, Pakistan’s economy has performed abysmally low recently and the failed infrastructural experiment in Sri Lanka is known to all. On the contrary, India has responded well to China’s plans by designing its own network of developmental projects in different regions like the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor, Project Mausam, and Spice route, etc. India has not promised anything big but has mapped a modest economic initiative that seems achievable.

Between 2004 and 2017, there were more than 20 violent strikes on Chinese nationals working in Pakistan. And it seems to have detrimental effects on the prospects of the China–Pakistan economic corridor (CPEC). Nonetheless, China and Pakistan have gradually moved towards deeper cooperation during recent years in spite of the continuous risk of attacks. The main explanatory factor apart from security priorities and economic potential is strategic interests. Sino-Pakistani cooperation was founded on a shared goal of countering India and balancing the influence of America in the region (Basit, 2018).

Analysis

In March 2013, Xi Jinping announced his epic vision to make ‘China Great Again’. China is leveraging its soft power to strengthen connections with neighbours through infrastructure diplomacy, earning strategic goodwill in the process (Rahul, 2018). CPEC is not just an economic project but also has clear political and security ramifications. Although CPEC has been boasted by both China and Pakistan to boost economic regionalism and connectivity, it is a twin-dimensional endeavour to safeguard its geostrategic sphere, which has both a continental and a maritime component (Saran 2015).

CPEC and China’s gains

The motivations for rolling up CPEC are both economic as well as political goals. Creating physical infrastructure will assist cut transportation times and costs while establishing soft infrastructure will allow for a greater range of items to be exchanged with fewer regulatory impediments. It will also give Beijing a much-needed alternate energy supply route, decreasing its existing reliance on the unpredictable and US-influenced route across the South China Sea. Energy transportation via this route currently takes around 45 days, which may be cut to less than 10 days if done via Gwadar Port. It is expected that transportation costs of all the Chinese trade via sea will also be reduced by 50%. As a result, the Gwadar–Xingjian route can be used as an alternative route for the transportation of energy, which will be time and cost-effective (Ahmed et al., 2020).

The corridor would provide China with enormous benefits since it would increase the number of trading routes connecting China to other regions. It will enable China to import energy and find new markets for its products in Central Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Strategically located near the Strait of Hormuz, Gwadar port represents both a new economic gateway and a military opportunity for Beijing. In the future, should China develop a navy robust enough to project credible power into the Indian Ocean, then the port will help Beijing to directly shape events in the Persian

Gulf (Ahmad & Hong, 2017). The corridor could help spur economic development in the landlocked western interior of China, as the creation of overland economic connectivity with Central Asia will boost growth there.

Part 1: Pakistan as a reliable partner for China’s Dream of CPEC

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is expected to deliver economic prosperity in the whole region. But the realization of the various potential developmental benefits is contingent on the effective completion of the several projects. The development of a corridor in the region must be economically feasible and should offer a satisfactory return on investment. And its success is also dependent on political stability as well as regional security. CPEC runs along the entire length of the Pakistani territory, which itself faces a myriad of problems (Sial & Pak Institute for Peace Studies, 2014). This raises the most crucial question: how practical is the realization of such a mega-project in a developing, politically unstable country with an exceptionally inadequate institutional, political, and administrative infrastructure?

Political Instability and Lack of Consensus

Pakistan’s domestic politics has never been stable where military and civilian leaders alternate in political authority. In fact, the Military controls all the major political and economic decisions. Due to the absence of civilian supervision, there is still secrecy and a lack of transparency surrounding the CPEC projects and routes, which is contributing to internal criticism of the project (Vinayak, 2020). The divergence of interests of both the civil and military leadership over the distribution of potential benefits of CPEC is further impeding its growth. The political consensus in Pakistan is also weak. There are also divisions between the provinces, particularly Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Punjab as well as divisions between the central authority and the provinces over the original route of the CPEC. Due to considerable opposition from regional governments, the Chinese may not be able to finish the Kashgar–Gwadar corridor. Since the inception of the initiative, protests from various parties, especially PTI, have caused delays in its inauguration. Even PTI won the election because of its opposition to the project. It also put light on the fact that people are not in favour of the project.

Mass Protest

The CPEC has remained the centre of protest in Pakistan due to China’s increasing involvement in Balochistan for squeezing out all the wealth from the region (Bishay, 2021).

The CPEC is viewed by people of Pakistan especially from Gwadar as a foreign occupation of their homeland and an attempt to marginalize the native Baloch people in the guise of economic development (Aamir, 2019). In order to protect Gwadar’s port town from insurgents, the government constructed a perimeter security fence with entry checkpoints. The removal of security check posts was one main demand of the massive protests that erupted in Gadar city on 22 November this year. The other reasons are the unavailability of basic needs like clean drinking water, electricity, and of course loss of livelihood of fishermen. Such resentments and anti-state feelings may make it impossible for the government to effectively undertake CPEC-projects in the long term. There is a chance of spread of this discontent in other parts of Pakistan considering the way of acquisition of land for infrastructure building. This process can be seen in Punjab province where people have to sell their agricultural land at very low prices. And the loss of agricultural land leads again to unemployment as no job has been provided in other sectors.

Poor Governance

The completion of CPEC is hindered by the lack of time and poor management ability on the part of Pakistani authorities. Furthermore, pervasive corruption, a lack of planning and management, such as land acquisition issues and poor development on various projects, have already substantially increased expenses. Pakistani officials have previously stated that several projects planned by China and Pakistan in 2010 may not be completed. While continued energy shortages and inadequate planning will impede CPEC progress and inflate the cost of individual projects.

Security concerns

As it stands, the intended corridor passes through two of the most volatile parts in this region: Balochistan and the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir, and the volatility surrounding both ends of this corridor may turn it into a risky venture for Chinese investment. The continuous insurgency in Balochistan province is the most critical impediment to the effective implementation of the CPEC project, as Gwadar port is critical to its success (Aamir, 2019). Moreover, the internal security situation in Pakistan, as well as the link between Pakistan-based terrorist groups and Muslim separatists in western China, is a source of concern for Beijing. Given the extent to which terrorist and militant groups have entrenched themselves in Pakistan, it seems difficult to save the CPEC from them.

Security concerns are among the most pressing concerns about the CPEC (Markey & West, 2016). Despite several anti-terrorism operations, Pakistan’s security situation remains perilous (Calabrese, 2016). The main impediment to the completion of CPEC is security. The Baloch insurgents are constantly attacking and kidnapping Chinese construction workers and project personnel. In Pakistan’s northwest frontier, road networks are planned to run near or through territories where the Pakistani Taliban and other anti-state militant groups could attack construction crews and even disrupt the flow of goods. Although Pakistan claimed that it had eradicated the ETIM from Pakistan, the threat of other militant groups still remains. Baloch insurgent groups, ETIM and TTP have frequently targeted a variety of development projects, blown up infrastructure including gas pipelines, targeted local labourers and civilians, and, most importantly, assaulted Chinese engineers working on the Gwadar project in the framework of CPEC. It appears that providing protection and security to Chinese citizens working on a variety of CPEC-related projects around the country would be a tedious task or a big challenge. Pakistan has deployed nearly 15,000 security personnel to safeguard roughly 7,000 Chinese nationals working on the CPEC (Khan, 2016).

As per analysts, CPEC’s security through these forces is feasible in the short term but as CPEC progresses, the presence of Chinese citizens will increase across Pakistan and it will be difficult to provide security to all of them (Shi & Lu, 2016). Recently, the insurgents have escalated the fight beyond Balochistan to avenge their allegation of Chinese exploitation of Balochistan’s resources (Joshi, 2021). Four individuals were slain in 2018 when armed gunmen attacked the Chinese consulate in Karachi. In 2020, four people were killed in another attack on the Pakistan Stock Exchange, which is mostly controlled by the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The terror strike on a bus in Dasu on July 14 was notable since it was the first time a large-scale Chinese-financed infrastructure project was attacked (Joshi, 2021).

Economic concerns

Pakistan’s economy is in shambles, with several macroeconomic issues such as expanding current account and budget deficits, falling foreign currency reserves, and unemployment. In 2019, Pakistan’s GDP growth rate fell below 1%. Pakistan’s economy has been in a catastrophic position, and this will badly affect the implementation of CPEC. Moreover, Pakistan is a semi-industrialized country with few industrial hubs or clusters. The majority of the projected industrial parks are still in the planning stages and would entail significant investment. Similarly, almost all of the missing linkages in the proposed connectivity projects will need massive expenditure. Given Pakistan’s perilous economic situation, such a large-scale investment may be unfeasible. Investment in Pakistan has dried up due to a weak law and order situation (Hussain, 2016). While Beijing would pay the majority of the CPEC initiative through commercial loans, soft loans, grants, and private equity investment, Pakistan is also expected to fund transportation projects. However, for nearly one decade, Pakistan’s average annual economic growth rate has not been more than 3 percent. Rising militant violence and perpetual political instability have made it difficult for the country to get FDI (Hussain, 2017).

The rising cost of the Project

The total value of the power and infrastructure deals concluded under CPEC has increased from the $46 billion investment plan originally announced in 2015 to an estimated $62 billion (Hussain, 2017). This rise in costs has resulted from the inclusion of Chinese financing for rail-based mass transit projects in various other areas. Moreover, the increasing cost of security is becoming a big problem in efficiently pushing forward the project. In 2015, Pakistani authorities decided to create a Special Security Division to defend Chinese interests and nationals in Pakistan (Ritzinger, 2015). And one percent of the cost of CPEC projects was directed towards this cause (Government of Pakistan, 2016).

The undulating and rugged topography and harsh climates

The northern route of CPEC (Karakoram Highway) passes over challenging mountainous terrain that rises to more than 5000m above sea level and is prone to landslides, extreme weather events, and earthquakes. And parts of the 805 km track are barely two-way, cut out of the rock face that drops abruptly into valleys below. Due to heavy snow, the Khunjerab Pass stays blocked from November to May; these harsh weather conditions also offer a slew of technical challenges for transportation businesses. Technical alternatives exist, but they are expensive, requiring costly rail and road tunnels as well as pipeline insulation and expensive pumping facilities, raising the project’s overall cost (Montesano, 2016, Nov 28).

Part 2: Implications for India

As aforementioned in the preceding section, CPEC has several challenges on its path to success. It is hard to believe that the Chinese are seeking to expand infrastructure in Pakistan simply because they have surplus infrastructure capacity and are searching for new markets for their products. While there may be some truth to this, no one takes such huge investment decisions when global demand is slumping (Malik, 2017). The primary rationale for China’s participation in Pakistan is obviously geopolitical rather than economic.

The real objective is to balance India by building and maintaining a Chinese presence in India’s backyard. The whole approach may be summed up as geo-positional balancing, which seems based on ancient Chinese concepts of geographical space (Callahan, 2008) or strategic encirclement tactics employed in the Chinese game of weiqi (Kissinger, 2011)2. Geo-positional balancing is a method of laying down marker stones’ in strategic geographical locations for potential future usage and as a hedge against potential disputes (Jeremy, 2018). Raj Verma has also argued that China requires Pakistan just to balance India in South Asia in order to keep the latter distracted, off-balance, and entangled in South Asian politics.

Strategic advantage

The selection of PoK for developing CPEC yields strategic advantages. It will extend China’s geographical reach within Pakistan, allowing the PLA to reach extremely close to India’s northern and western frontier Ladakh is crucial for upholding Indian presence on the Siachen Glacier since it allows a physical route to the frozen battlefield and connects it with the rest of the country. And west of the Siachen glacier, across the Saltoro Ridge, lies Pakistan-controlled Gilgit-Baltistan (Bhatt, 2019). East of it lies China-occupied Aksai Chin. By keeping its presence on the Siachen glacier, India has managed to keep China and Pakistan apart (Storey, 2006). These infrastructure projects under CPEC will consolidate China’s control over PoK to tie India down in the region. The Chinese road network via Shaksgam, which connects the Karakoram Highway to the Tibet Xinjiang Highway, would enclose J&K on three sides (Lee, 2016). While the feeder roads connect significant military complexes in China and Pakistan, Gilgit provides natural cover to military

2 Weiqi is a popular Chinese strategic board game involving attempts to encircle the opponent or to resist encirclement by the opponent by putting down black or white stones. installations such as missile sites and tunnels, increasing their joint capacity and allowing them to undertake collective attacks against India (Sering, 2012).

Encirclement of India

China has aggressively followed its policy of “string of pearls” to encircle India (Frankel, 2011). Outposts and airstrips linked by road-rail networks support China’s dominant position on the Tibetan plateau to the north. The Xinjiang-Lhasa train link is edging close to Nepal, where China has made considerable political gains. To India’s east, China will have access to the Bay of Bengal through transportation and pipeline links to Kyaukpyu port in Myanmar. In the west, CPEC will provide access to the Arabian Sea from Xinjiang via Gilgit-Baltistan to the Gwadar port. Further west, China has established its first overseas military base in Djibouti. To our south, China has constructed Hambantota port in Sri Lanka. So, India’s encirclement from the north has been accompanied by a maritime encirclement (Jain, 2017)

Increasing Chinese influence in India’s Ocean

China intended to counter the Indian predominance in the IOR by ensuring its permanent presence in the Indian Ocean. The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is important in the whole layout of CPEC where Hambantota and Gwadar seaports connect two important dots in the string of pearls strategy (Financial Times, 2017). Additionally, Gwadar has the strategic potential of becoming China’s military base. If the Gwadar port is developed into a military base, the Chinese Navy will have a permanent platform in the Indian Ocean (Rehman et al., 2021). If China maintains its naval presence in the Arabian Sea, it may be able to dominate the Strait of Hormuz via the seaport of Gwadar. This would put India’s regional diplomatic and military capabilities to the test (Kanwal, 2018).

Many Islands of Lakshadweep are located in the Arabian Sea. And India has been actively conducting many economic zones, exclusive export zones, and naval bases in the Arabian Sea (Jain, 2017). Moreover, the assertiveness with which China has acted in the South China Sea can be a reference for India that if China establishes a footing in the Arabian Sea, and hence in the Indian Ocean via Gwadar, it may make national interest claims in India’s maritime region as well (Ghiasy & Zhou, 2017). Moreover, it cannot be denied that Beijing’s ports in the Indian Ocean will have dual-use facilities, i.e. both economic and military. Such a development will further complicate India’s security calculus in the region. To further strengthen its military grip and presence in the Indian Ocean, China is quietly looking to establish a new military base in Jiwani, which is about 80 km to the west of the Gwadar Port. Such activities undertaken by China in the region and especially near the strategic port are obviously a threat to India’s security.

Threat to Energy Security

India is highly dependent on energy imports for its economic growth. India imports over 60% of its oil supplies passing through the Strait of Hormuz mainly from Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq. India has sought to secure shipping lanes for the transportation of oil from the Middle East. Any disruptions in the Indian Ocean can lead to serious consequences for the Indian economy. Located a mere 600 km from the Strait of Hormuz, Gwadar places China in close proximity to the Iran-controlled water channel, which supplies 35% of the world’s oil requirements. China’s permanent maritime presence at the narrow entrance of the Persian Gulf can be a risk to India’s energy security.

Traditional Security Threats

CPEC has the weight to alter the geopolitics of this region. The linking of Karakoram with Gwadar, both having commercial and military significance, can potentially act as strategic chokepoints with regard to India. The Karakoram ranges are the northernmost and also form the de facto border along which runs the Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China.

As China has already built 36 Kms of road in the Shaksgam Valley and most probably PLA will link the G-219 (Lhasa- Kashgar) highway to Karakoram Pass, through the Shaksgam Pass. This will enable the PLA to put pressure on the (DBO) Daulat Beg Oldi defences from the North. Once DBO is won by the PLA the route to Siachen via Sasser La Murgo-Sasoma, (Base on Nubra River just south of the Siachen base) can be reached in no time (Lal, 2020).

China has also built 16 airstrips all along Karakoram Highway, mostly for military operations. This would be important for enhancing Pakistan and China’s strategic airlift capabilities and ensuring smoother logistical support (Prasannan, Ahuja & Sagar, 2021). In the future instance of an India-Pakistan war, China can launch a pincer attack to threaten India and trap its armies in the Ladakh region. China can also keep an eye on the Indian activities in the region by establishing listening posts and advanced surveillance bases in PoK (Gupta, 2017). The route of the CPEC can provide easy transportation of military hardware to Pakistan if the conflict between India and Pakistan rises.

There are apprehensions that terrorist activities will be motivated and will grow more easily because of CPEC because increasing activities along the Indian border will also make PoK more suitable to trespass by terrorists. Recently, the Taliban has also shown interest in joining CPEC. Sawhney (Prasannan, R., Ahuja, N. B., & Sagar, P. R., 2021, September 12) argued that with Kabul likely to join the axis, the military threat will convert into a strategic threat.

Threat to India’s Sovereignty

The CPEC route is going through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) and Gilgit-Baltistan. Both are Pakistan-occupied territories claimed by India and subsequently disregard India’s sovereignty (Patil, 2015). If CPEC is a success, it will reinforce the region’s status as a globally recognised Pakistani territory, undermining India’s claim to the 73,000-square-kilometer area. There have also been reports of an increased presence of Chinese troops in the PoK (Chansoria, 2016).

Effect on India’s Defence Strategy and budget:

This would also constrain India’s plans to reshape its strategic priorities, especially the aim of increasing its maritime capabilities. An increased Chinese military presence on India’s northern border could see India shelve or curtail plans for its naval expansion in favour of reinforcing Army and Air Force capabilities. In last year’s budget, almost 56% of the total defence outlay was earmarked for the Indian Army. The Air Force and Navy were allocated 23% and 15% respectively.

And in an effort to strengthen its existing continental capabilities, India will soon raise a mountain strike corps primarily in response to the rising PLA’s presence along India’s borders. Questions remain about the three existing strike corps, based in central India and covering Pakistan. The important question is how the mountain corps could be raised within the current allocation of resources for the Indian Army because out of the total allocated budget only 18% constituted capital expenditure while the rest was revenue expenditure. A second problem, the increased Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean, means that India is under an obligation to increase the strength of its Eastern Fleet, which may mean shelving the plans for raising the Army’s mountain corps (Chandramohan, 2013).

Conclusion

The CPEC is not only the BRI’s flagship project but also plays a key role in Beijing’s global ambitions (Adeney and Boni, 2021). Its importance lies in the fact it is a link between the road and Maritime dimensions of China’s BRI project. CPEC is expected to reduce the logistical cost and transportation time for Chinese trade by providing a shorter route to the Persian Gulf. It will make China overcome the Malacca Dilemma. The building or operating projects abroad is not merely a security problem; it also involves politics and diplomacy. Apart from geographic location, local support, politics, economic circumstances, security conditions, and people’s needs are all variables to consider when choosing a region for project investment. Pakistan’s prevailing environment of insecurity which is rife with Islamic militancy and domestic insurgency is posing serious threats to the construction of the corridor (Hassan, 2019). Moreover, Pakistan is a country that lacks a stable political order and is plagued by corruption and the military’s monopoly. Pakistan is already a bankrupt state, so no return can be expected and even the principal amount is at risk. There are also mass protests occurring in various parts of Pakistan against CPEC. China needs to approach with caution because things can be turned around unexpectedly. All of these factors have already hampered the progress of numerous CPEC projects. Further, a close assessment of Pakistan’s role in the implementation of CPEC, Pakistan’s position as a reliable partner is highly questionable.

The CPEC can be a serious challenge to India’s political, strategic, and economic interests if it becomes a reality. Conventional wisdom has it that India can be worried about CPEC at its two ends: Gwadar, where the Chinese are building a maritime presence, and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, where Pakistani and Chinese territorial and military frontiers are merging. CPEC looms in on the sovereignty and security of India. Since the inception of the corridor, the concentration of PLAs troops is only on an upwards swing exhibiting rising militarization of the area. The presence of the Chinese military in Pakistan does not fare well with Indian security on its Western borders. The CPEC can be seen as a platform that would allow China to increase its naval presence in the Indian Ocean and to increase its geopolitical stake in the IOR. The Indian Ocean is a significant part of India’s national interest and foreign policy. This would become a challenge to India’s regional diplomatic and military capabilities.

The best battles are fought at a time and place of your choice (Sinha, 2020). While no one should advocate for war, it seems imperative to be well prepared for it. It would be much better if India could create more political virtual battlefields. India may counter China by dropping its stated stance on the One China Principle and challenging Chinese attempts to dominate maritime chokepoints. India should continue to strengthen its marine capabilities through cooperative agreements with the United States, France, Japan, and Australia, while also boosting its own military’s capacity to protect itself sufficiently. India should also focus on modernizing its technological capabilities like electronic and cyber, Precision Guided Munitions, Space, and other advances.

To protect its most vital assets in the IOR, India should concentrate on a few strategically critical routes and ports along its adjoining seas and islands. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands should be developed as a modern transit and shipping base. The next step would be to develop Chabahar port in the west with road/rail connections to Central Asia; Trincomalee Port in the east with maritime linkages to Bay of Bengal littoral ports and beyond; and the Mekong-Ganga corridor connecting India’s east coast with Indo-China. To secure its northern border, India should work closely with and try to improve relations with its neighbours and also adopt CBMs with Nepal, Bhutan, and Myanmar. Along the KKH belt, India should also fortify the whole defence complex of Siachen-DBO-Galwan Valley-Fingers at Pangong Tso since all of these outposts are operational and strategically important. New Delhi should also scale up its defences along Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim borders with China and improve regional connectivity with the North-Eastern states.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies

Title image courtesy: Tribune India

Article courtesy: Electronic Journal of Social and Strategic Studies Volume 2 Issue 3 Date of publication: 20 December 2021 December 2020-January 2021 https://doi.org/10.47362/EJSSS.2021.2310

References

Aamir, A. (February 15, 2019). The Balochistan Insurgency and the Threat to Chinese Interests in Pakistan. Jamestown. Retrieved October 26, 2021, from https://jamestown.org/program/the Balochistan-insurgency-and-the-threat-to-Chinese-interests-in-Pakistan/

Ahmad, R., & Mi, H. (2017). China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and its Social Implication on Pakistan: How will CPEC boost Pakistan’s Infrastructures and Overcome the Challenges. Arts and Social Sciences Journal, 2, 265–273. [Google Scholar]

Ahmad, R., Mi, H., & Fernald, L. W. (2020). Revisiting the potential security threats linked with the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 1(1), 64-80. 10.1080/26437015.2020.1724735

Adeney, K. and Boni, F. (2021). How China and Pakistan Negotiate. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/05/24/how-china…

Basit, S. H. (2018). Terrorizing the CPEC: managing transnational militancy in China–Pakistan relations. The Pacific Review. 10.1080/09512748.2018.1516694

Bhatt, P. (2019, November). Revisiting China’s Kashmir Policy. Observer Research Foundation, ORF Issue Brief. 326. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.orfonline.org/research/revisiting-chinas-kashmir-policy-58128/

Bishay, N. (2021). The Republic World. ‘Gwadar ko Haq do’:Pakistani women, children join protest against China’s CPEC project & Imran Khan govt. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.republicworld.com/world-news/pakistan-news/pakistani-women-children join-protest-against-chinas-CPEC-project-and-Imran-khan-govt.html

Boon, H. T., & Ong, G. K. H. (2020). Military dominance in Pakistan and China–Pakistan relations. Australian Journal of International Affairs. 10.1080/10357718.2020.1844142

Calabrese, John. (2016, December 20). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC): Underway and Under Threat. MEI@75. Policy Analysis. Retrieved August 30, 2021, from https://www.mei.edu/publications/china-pakistan-economic-corridor-cpec-underway-and under-threat#_ftn6

Callahan, William A. (2008). Chinese visions of world order: post-hegemonic or a new hegemony? International Studies Review. 10. 751.

Chandramohan, B. (2013, July 16). India’s Defence Budget: Implications and Strategic Orientation [Strategic Analysis Paper]. Future Directions International. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.futuredirections.org.au/wp content/uploads/2013/07/FDI_Strategic_Analysis_Paper_-_16_July_2013.pdf

Chansoria, M. (2016). China’s Current Kashmir Policy: Steady Crystallisation. Journal for the Center of Land Warfare Studies. 68-80. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://claws.in/images/journals_doc/1879857213_2078418284_MonikaChansoria.pdf.

Financial Times. (2017). How China Rules The Wave. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://ig.ft.com/sites/china-ports/?mhq5j=e1

Frankel, F. R. (2011). The Breakout of China-India Strategic Rivalry in Asia And The Indian Ocean. Journal of International Affairs, 64(2), 1–17. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2438553

Garlick, J. (2018). Deconstructing the China Pakistan Economic Corridor: Pipedreams versus Geopolitical Realities. Journal of Contemporary China. 10.1080/10670564.2018.1433483

Ghiasy, R. & Zhou, J. (2017). The Silk Road Economic Belt: Considering Security Implications and EU-China Cooperation Prospects. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/The-Silk-Road Economic-Belt.pdf

Government of Pakistan. 2016. Annual Plan 2016–17. Islamabad.

Gupta, Brig. A. (2017, Oct 5). Karakoram Highway: A security challenge for India. Indian Defence Review. Retrieved October 9, 2021, from http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/karakoram-highway-a-security-challenge-for India/

Haldar, S. (2018). Mapping Substance in India’s Counter – Strategies to China’s Emergent Bett and Road Initiative: Narratives and Counter-narratives. India Journal of Asian Affairs, 31(1/2), 75-90. Retrieved September 14, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26608824

Hassan, K. (2019). CPEC: A Win-Win For China And Pakistan. Human Affairs, 30. 212–223. 10.1515/humaff-2020-0020

Hussain, Dr. E. (2016). China–Pakistan Economic Corridor: Will It Sustain Itself? Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 10. 10.1007/s40647-016-0143-x

Hussain, Z. (2017, June). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and the New Regional Geopolitics. Asie.Visions. 94. Ifri. ISBN: 978-2-36567-738-7. Retrieved October12, 2021, from

https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/hussain_china_pakistan_economic_corri dor_2017.pdf

Jain, S. K. (2017, July). Growing Presence of China in Pak Occupied Kashmir and India’s Concerns. World Focus, XXXVIII(7), 138-141. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Arif-Malik

2/publication/318528293_Rehabilitation_Policy_A_Field_Study_of_PoK_Returnee_Milita nts/links/5cc46ee1299bf1209784c31c/Rehabilitation-Policy-A-Field-Study-of-PoK Returnee-Militants.pdf#page=138

Joshi, P., & Vivekananda International Foundation. (2021). China Pakistan Economic Corridor: Domestic Trajectory and Contested Geopolitics. National Security, 4(3), 234- 253. ISSN 2581-9658

Kanwal, G. (2018). Pakistan’s Gwadar Port: A New Naval base in China’s String of Pearls in the Indo-Pacific. CSIS Brief. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/pakistans-gwadar-port-new-naval-base-chinas-string-pearls indo-pacific

Khan, R. (2016, August 12). 15,000 troops of the Special Security Division to protect CPEC projects, Chinese Nationals. Dawn. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.dawn.com/news/1277182

Kissinger, H. (2011). In China. United Kingdom: Penguin Books Limited. 23–25. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/On_China/GldTEJnmbeAC?hl=en&gbpv=1

Lal, A. K. (August 9, 2020). The CPEC challenge and the India-China standoff: An opportunity for war or peace? Times of India. Retrieved August 25, 2021, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/rakshakindia/the-cpec-challenge-and-the-india china-standoff-an-opportunity-for-war-or-peace/

Lee, P. (2016, May 11). The World’s Most Dangerous Letters Are Not SCS…They’re CPEC. China Matters. Retrieved October 9, 2021, from http://chinamatters.blogspot.com/2016/05/the-worlds-most-dangerous-letters-are.html

Malik, H. Y. (2012). The strategic importance of Gwadar Port. Journal of Political Studies, 19(2), 57– 69. [Google Scholar]

Malik, A. (2017, May 6). OBOR: For India, it is a road to subjugation. The Pioneer. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://bit.ly/2nTS4CU [Google Scholar]

Markey, D. & West, J. (2016, May 12). Behind China’s Gambit in Pakistan. Council on Foreign Relations. Expert Brief. Retrieved December 1, 2016, from http://www.cfr.org/pakistan/behind-chinas-gambit-pakistan/p37855

Meyer, M. W., & Zhao, M. (2019, April 30). China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Why the Price Is Too High [Podcasts, Wharton Business Daily]. Wharton, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/chinas-belt and-road-initiative-why-the-price-is-too-high/

Montesano, Francesco S. (2016, Nov 28). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Security Challenges at a Geopolitical Crossroads. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/The_China_Pakistan_economic_Borde r_def.pdf

Patil, S. (2015, May 14). OBOR and India’s Security Concerns. Gateway House. Retrieved August 23, 2021, from https://www.gatewayhouse.in/security-implications-of-chinas-transnational corridors/

Prasannan, R., Ahuja, N. B., & Sagar, P. R. (2021, September 12). The potential axis of Taliban, China, and Pakistan could be a cause for worry for India. THE WEEK. Retrieved October 19, 2021, from https://www.theweek.in/theweek/cover/2021/09/02/alarming-axis.html

Rahman, Z. U., Khan, A., Lifang, W., & Hussain, I. (2021, January 26). The Geopolitics of the CPEC and the Indian Ocean: Security Implication for India. Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs, 13(3), 122-145. 10.1080/18366503.2021.1875807.

Rahul, A. (2018). The Game for Regional Hegemony: China’s OBOR and India’s Strategic Response. Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy & International Relations, 7(13), 159- 196.

Ritzinger, L. (2015). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Regional Dynamics and China’s Geopolitical Ambitions. The National Bureau of Asian Research. Seattle, WA. Retrieved October 26, 2021, from https://www.nbr.org/publication/the-china-pakistan-economic corridor/

Saran, Amb. S. (2015). What Does China’s Global Economic Strategy Mean for Asia, India, and The World? Institute of Chinese Studies. Delhi. No. 35. Retrieved from on November 19, 2021, from https://www.icsin.org/uploads/2015/10/09/677d627ad1f9ba3cd77c0bbdd5389f98.pdf

Sering, Senge H. (2012). Expansion of the Karakoram Corridor: Implications and Prospects. IDSA Occasional Paper No. 27. 9. Retrieved September 13, 2021, from https://idsa.in/system/files/OP_Karakoramcorridor.pdf

Shi, Z., & Lu, Y. (2016, December 21). The benefits and risks of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from http://carnegietsinghua.org/2016/12/21/benefits-and-risks-of-china-pakistan-economic corridor-pub-66507

Sial, S., & Pak Institute for Peace Studies. (2014, July-December). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: an assessment of potential threats and constraints. Conflict and Peace Studies, 6(2). Retrieved October 26, 2021, from http://pakistanhouse.net/wp content/uploads/2016/11/cpec.pdf

Sinha, S. (2020, July 4). The Karakoram and other factors in India-China Standoff. The Sunday Guardian.

Storey, I. (April 12, 2006). China’s Malacca Dilemma. China Brief. 6 [8]. The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved October 9, 2021, from https://jamestown.org/program/chinas malacca-dilemma/

Vinayak, A. (2020, May 23). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor of the Belt and Road Initiative Concept, Context and Assessment by Siegfried O. Wolf, Springer [Book Review]. Vivekananda International Foundation. Retrieved October 30, 2021, from https://www.vifindia.org/bookreview/2020/may/23/the-china-pakistan-economic-corridor of-the-belt-and-road-initiative-concept