The global geopolitical landscape is undergoing profound change. The emergence of new powers, particularly China and Russia, is disrupting the post-World War II established international order, dominated by the United States and its Western allies. In this context, the BRICS bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) is asserting itself as an increasingly influential economic and political actor, challenging Western hegemony. One of the BRICS’ flagship projects is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a vast infrastructure investment program aimed at strengthening trade and cultural links between China and the rest of the world. The Digital Silk Road (DSR) is its extension into the virtual world, aiming to weave a network of digital infrastructure connecting BRICS member countries.

This article analyzes the geopolitical potential of the DSR, its implications in terms of economic cooperation, cybersecurity and global digital governance. It also examines the interests and challenges of the European Union in the face of this BRICS initiative.

The DSR: Engine of Economic Growth and Geopolitical Lever for the BRICS

- Objectives and Ambitions of the DSR

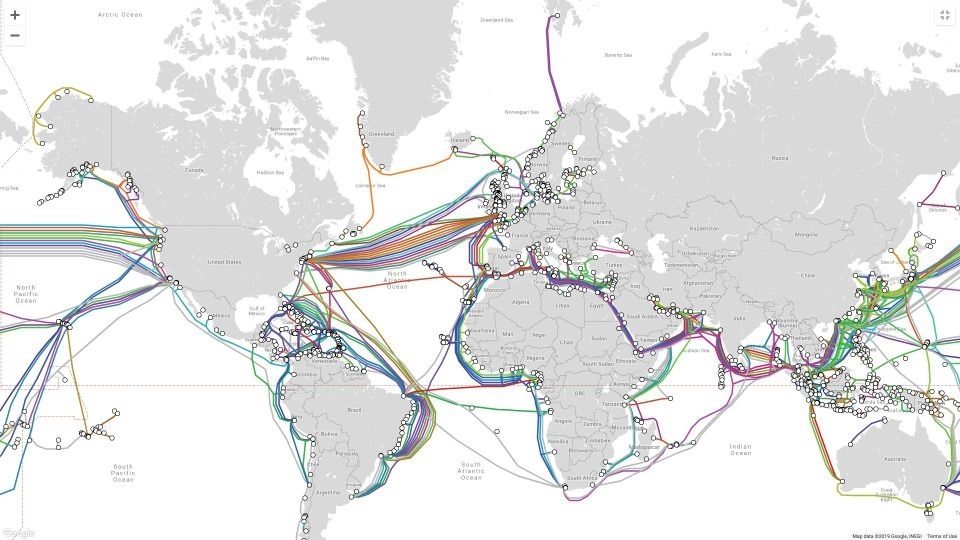

Officially launched by China in 2015, the DSR has several objectives. Economically, it aims to stimulate the growth of BRICS countries by massively investing in digital infrastructure: submarine cable construction, 5G deployment, e-commerce development, etc. Geopolitically, the DSR is seen as a tool for China to expand its technological and ideological influence over its BRICS partners and beyond. Behind the official rhetoric of “shared destiny of mankind”, the DSR would allow Beijing to export its technological standards, industrial norms and authoritarian political values.

- Economic Development Potential

By massively investing in the digital infrastructure of developing countries, the DSR could generate significant economic benefits, starting with the BRICS countries themselves. By 2025, the DSR is expected to inject more than $2 trillion into the global digital economy. Beyond the coveted markets of Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa, the DSR is also an opportunity for Chinese tech giants to expand their digital footprint into strategic regions such as Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa. By accelerating the digital transformation of these emerging economies, the DSR will stimulate trade and investment flows for the benefit of BRICS countries.

- The DSR, a Soft Power Tool for the BRICS

The DSR is part of China’s soft power outreach strategy. By exporting its technologies and industrial standards through the DSR, China seeks to strengthen its technological and ideological leadership within BRICS but also in the rest of the world. For instance, in telecommunications, China is actively promoting Huawei’s 5G technology to its partners, to the detriment of Western technologies. In artificial intelligence, Chinese giants like Alibaba or Tencent already occupy a dominant position in many developing countries. In the long run, the DSR could allow China and the BRICS to institutionalize a “Beijing Consensus” based on political values potentially antagonistic to the Western democratic model. Behind the promised digital connectivity of the DSR, there may also be an expansionist political project piloted by Beijing.

Cybersecurity: A Key Issue for the Credibility of the DSR

- Increased Risks of Cyberattacks and Mass Surveillance

Although promising economically, the DSR raises legitimate concerns about cybersecurity, personal data protection and respect for human rights. The increased connectivity of BRICS digital networks and the widespread adoption of Chinese technologies inherently increase the risks of cyberattacks, industrial espionage and state surveillance of citizens. China in particular is regularly criticized for its offensive cyberespionage practices targeting both the United States and Europe as well as political dissidents and the Uighur Muslim minority on its own territory. In this context, it is difficult to trust Beijing and Chinese tech giants to ensure the cybersecurity of DSR infrastructure, both within BRICS and in other partner countries.

- Cybersecurity Cooperation: A Challenge for the BRICS

To alleviate these criticisms and strengthen the credibility of their initiative, the BRICS must urgently strengthen cooperation on cybersecurity. This involves developing common standards, sharing information on cyber threats and training qualified experts in national cybersecurity agencies. The establishment of inter-BRICS institutions specialized in cyber risk prevention, modeled on ENISA in Europe, should also be considered. In the long run, the level of cybersecurity provided by the BRICS will directly influence the adoption of the DSR by other coveted countries. Without adequate safeguards, many states will prefer to keep their distance from a project perceived as a digital Trojan horse piloted by Beijing at the expense of national security and individual freedoms.

The Governance of the DSR: Towards a Fragmentation of the Internet?

- Challenging the Current Global Internet Governance

So far, global internet governance has been largely dominated by Western countries and a few American multinationals such as Google, Amazon or Facebook. However, the deployment of the DSR marks the desire of the BRICS to weigh more heavily in the direction and regulation of global digital networks. Behind the rhetoric about the “democratization” and “multilateralization” of the internet lies an influence struggle between two radically different models: on the one hand, the liberal model historically led by the United States; on the other, an authoritarian model piloted by China and exported via the DSR to the rest of the world. The ongoing confrontation between these two powers for global technological leadership suggests a profound fragmentation of digital space along antagonistic geopolitical lines.

- The Difficult Balance Between National Interests and Global Digital Commons

Beyond this Sino-American confrontation, the DSR more broadly raises the issue of balancing national logics with global digital commons. How to reconcile the legitimate interests of states, particularly in terms of national security, with the necessary international cooperation to regulate virtual spaces that are inherently transnational? To what extent are the BRICS willing to share certain sovereign prerogatives in cyberspace to bring about genuine multilateral governance of the internet? This seems doubtful when we see China or Russia considerably strengthening their state control over their national internet segment, in contempt of universally shared democratic values.

What Strategy for the European Union vis-à-vis the DSR?

- Opportunities and Risks for European Interests

Given its economic and political weight, the European Union cannot ignore such a large-scale digital integration project led by the BRICS. On the one hand, the DSR represents real opportunities for cooperation with these new emerging powers in key sectors such as 5G, cloud computing, artificial intelligence or smart cities. On the other hand, the EU shares the same concerns as the US about the risks that the DSR, under Chinese influence, poses to European interests, whether economic (industrial espionage), geopolitical (spread of digital authoritarianism) or security (cyberattacks).

- The European Response: Technology, Cooperation and Soft Power

Faced with this risk of digital vassalization, Europe must respond firmly. First, by investing massively in technological innovation to maintain its leadership in cutting-edge fields such as 5G, quantum computing or blockchain. The challenge here is to avoid excessive dependence on Chinese technologies on its own soil. Then by strengthening technological and security cooperation within the EU itself and with its traditional allies, the US first and foremost. Ambitious joint projects with Washington have been launched in cloud computing and artificial intelligence. The goal: present a united front in the face of the challenges posed by the BRICS and China in particular.

Finally, Europe must give more weight to its own digital model based on democratic values and respect for individual freedoms. This “European-style soft power” could appeal to many countries torn between the promises of the DSR and the fear of a “Big Brother” made in China.

Conclusion

With its Digital Silk Road project, China and the BRICS have undoubtedly scored points both economically and geopolitically. But the lack of transparency and the inherent risks of the DSR in terms of cybersecurity or citizen surveillance seriously tarnish its brand image. To succeed, the BRICS will have to dispel these many doubts that undermine the confidence of states and individuals in this still ill-defined initiative. As for the European Union, it must strongly react technologically to maintain its digital leadership in the face of China’s rise to power. The coming years will determine whether the DSR is an opportunity or a threat to global digital equilibrium.