Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has unleashed a heated debate in international relations academic circles. As is often the case with events of such magnitude, old discussions between different theoretical schools are rekindled.

For several decades, the debate has been dominated by the neo-realists and the neo-liberals (with their different strands). Other minor – but no less interesting – schools, such as constructivism, neo-Marxism, and socio-cultural studies, have timidly tried to creep in.

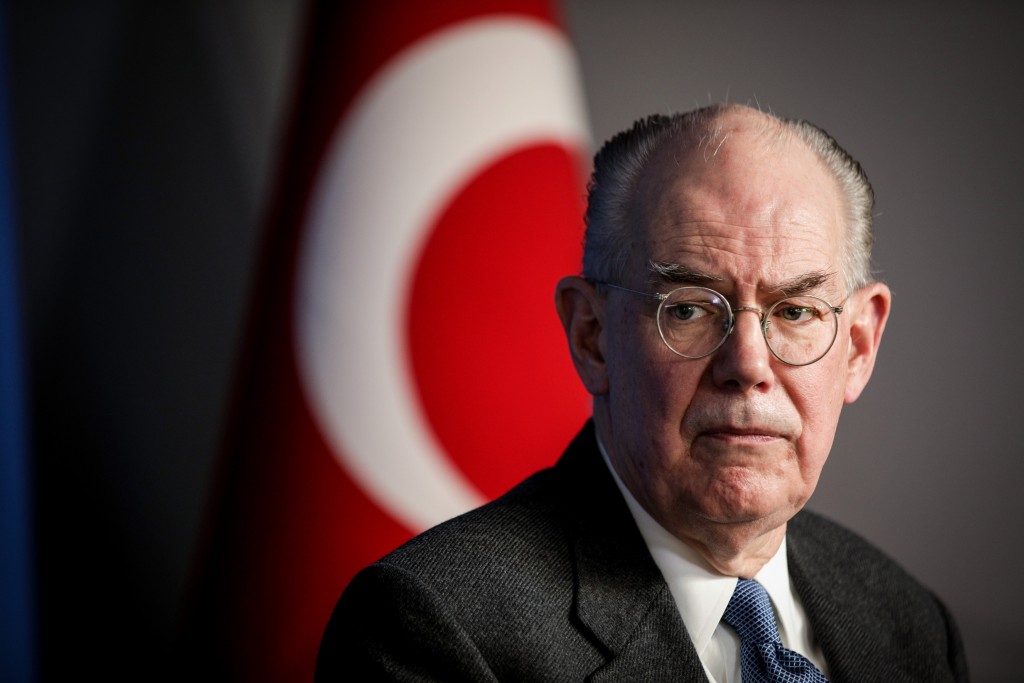

In particular, the war between Russia and Ukraine brought the polemic Professor John Mearsheimer, father of the offensive side of structuralist neorealism, back into the limelight. According to this school, great powers are inevitably forced to compete and aggress. The “security dilemma” cannot be resolved and aggression is the only rationality for self-preservation.

This aggressive behaviour of the great powers will be the main factor of change in international relations. And that is the “tragedy” of the great powers, according to Mearsheimer: “The great powers are permanently looking for opportunities to increase power at the expense of their rivals, with hegemony as their ultimate goal” (The Tragedy of the Great Powers, 2001). According to this particular vision, the status quo is only sought by those who have managed to secure a hegemonic position. The international system is basically composed of great powers with revisionist intentions.

Following the decision by the President of Russia to invade Ukraine, Mearsheimer’s supporters recalled an intervention of his in 2015, when he “predicted” that it would be best for Ukraine to sustain a neutral position or else it would be “torn apart” by Russia. But these supporters omitted several elements. First, Mearsheimer made his prediction with Monday morning quarterback in the wake of the Russian invasions of Georgia in 2008 and Crimea in 2014. In fact, Putin’s national security concerns, in the face of possible NATO expansionism, were made crystal clear in his famous speech to the Munich security conference in 2007.

So Mearsheimer did not actually predict anything. This war was perfectly avoidable if many things had happened, which unfortunately did not happen and have nothing to do with the assumptions of offensive realism. For example: If Putin had fallen in disgrace and another pro-Western political force ruled Russia today. Or if NATO had agreed to negotiate with Putin, since 2007. Even, though less likely, if Putin had changed his mind and strategy. It is clear that the possibilities of avoiding this catastrophe were many and had nothing to do with the fatal “tragedy” that Mearsheimer presents to us.

Mearsheimer is characterized by a deterministic approach in that the forces of international politics drive leaders to act as they do and he is convinced of the conflicting inevitability of competitive dynamics. But what determinism, what “forces”? There is no doubt that the predominant forces in international politics are leaders and their people. This is proven by historical evidence. They are the sole makers of that history. It can always be directed to the side they decide. As Putin is doing at the moment.

On the other hand: what “conflicting inevitability”? Mearsheimer is famous for the wars and conflicts he supposedly predicted. But we cannot overlook all the wars that have been avoided, thanks to diplomacy and the vocation of cooperation that tends to prevail among States, whether by values or by interests. And which have flatly refuted the deterministic assumptions of offensive realism.

China is an actor whose behaviour makes Mearsheimer uneasy.

Finally, it is interesting to mention Mearsheimer’s perception of China, an international actor that clearly dislocates him and forces him to say certain things in order to fit it into his contrived assumptions. Mearsheimer cannot explain, for example, how it is that China does not initiate or participate in wars and how it has been one of the main supporters of US-led capitalist globalization. However, the scholar frames both powers in an “inevitable rivalry”, where the margin for cooperation is minimal.

In this sense, Mearsheimer is also unable to explain the paradox that China, the “rising hegemon”, which would supposedly be “forced” to attack (out of necessity and opportunity), on the contrary, has recently had to defend itself from aggression (for now in the economic sphere) by the US. And how is it that these two superpowers still maintain the largest economic relationship in the history of mankind? We are talking about annual exchanges of more than US$ 500 billion which, to the surprise of the Mearsheimer’s of this world, even grew by 28% in 2021.

To conclude, the danger of Mearsheimer, as with other authors such as Graham Allison and his “Thucydides trap”, is that they end up making a great contribution to what may become self-fulfilling prophecies. Because their influence on the political and economic elites of the West is undeniable. And it is also palpable the great interest they arouse in the academic field, due to the simplicity and attractiveness of their assumptions. There is no denying the contributions of this school, as of any other in international relations. But it is very important to debunk certain myths.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies

Title image courtesy:https://theintercept.com/2022/03/06/russia-john-mearsheimer-propaganda/

Article Courtesy: ReporteAsia