Ethnicity is argued to be one of the most neglected determinants in understanding the political changes currently happening in Afghanistan. The fact there is a multitude of ethnic groups inhabiting Afghanistan is studied and deliberated upon for a long time. The problem however has been in identifying how ethnicity itself can be a deterrent with respect to ‘political reconstruction’. With the fall of Kabul and the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the question of representation of minority ethnic groups has been of growing concern. The basic response from the Taliban spokesperson Suhail Shaheen, has been that the future government will represent people from every ethnic group. But the reports on the persecution of the Hazara families by Amnesty International paints a different picture.

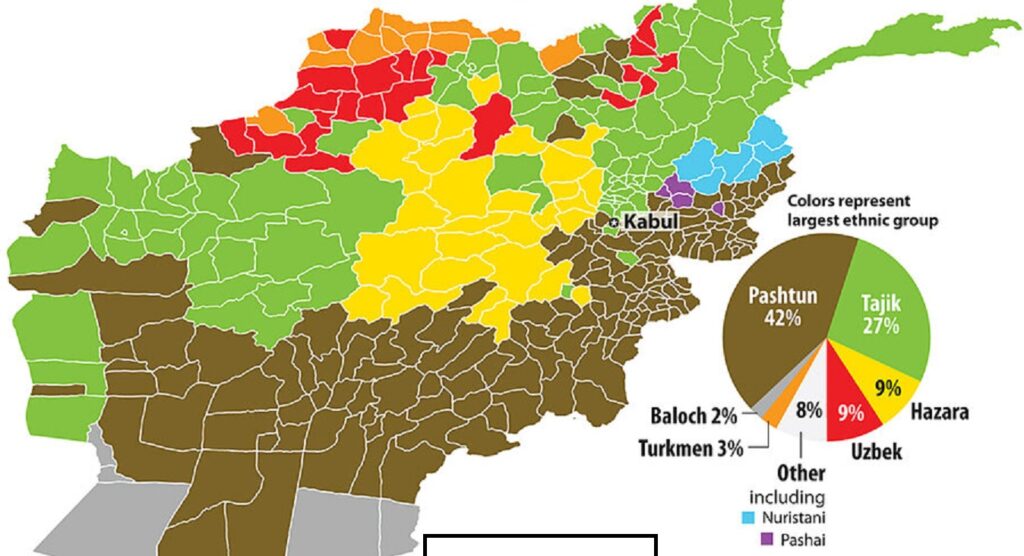

Here, it is important to define ethnicity and argue how it is such an important variable in Afghan Politics. Castell in his seminal work “ The Power of Identity: Economy, Society, and Culture” defines ethnicity as the construction of identities from geography, history, biology, and other facets of collective memory. Thus, it can be attributed to the most primitive sense of self-identification. With respect to Afghanistan, the nature of ethnic groups and their identification has evolved over time. Earlier, in the 18th-century identities like ‘Hazaras’ and ‘Shiite’ were synonymous in nature. Tajiks were the group who were primarily non Pashtuns, i.e who did not speak Persian. The word ‘Pashtun’ in Persian is a synonym of the word ‘Afghan’. The 19th century marks the beginning of explorers and soldiers coming in with their own understanding of how to identify the inhabitants of the region. The primary example of this ethnic taxonomy starts with Henry Bellew’s report. Here, he mentioned around eight major ethnic groups. While the national anthem of Afghanistan recognizes around 14 major groups, namely Pashtuns, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Balochis, Tajiks, Turkmens, Nooristanis, Pamiris, Arabs, Gujars, Brahuis, Qizilbash, Aimaq, and Pashai. The existence of groups like Pashai, Mountain Tajiks, came way later with anthropologists like Franz Schurmann (1962) coming into the picture in the late 20th century.

The signing of the Durand Line Treaty with the British, by Amir Abdul Rahman in 1893, was a point where a major Pashtun-dominated region was ceded away. Still Pashtuns being rulers were the dominating group, even though Tajiks and Qizilbash were in charge of the bureaucracy. The aspect of the “ethnic divide” was still not consolidated during these years. In the next half-century, we witness ethnicity playing a major role with respect to political constructions. Groups like Setam-e-Milli, Afghan Millat are coming into the political arena calling for the Pashtun political front. Over the next decade, around the later part of the 20th century, the Soviet Invasion is changing the political dynamics of the region. The Pashtun domination is severely challenged, with the emergence of the non-Pashtun representation from the Uzbeki, Balochi, Nooristanis under the leadership of the Parcham faction right after the 1979 invasion. This was a period of great political tussle, with Najibullah failing to unite Afghanistan. His failure gave birth to the Afghan Civil War. This period of anarchy further dissolved the leftover influence the Pashtuns had in state politics. The eras of the mujahideen’s were even more tumultuous, which served as a breeding ground for the Taliban to rise.

The fall of Kabul in 1996, was followed by hanging Najibullah’s corpse in public display. The Taliban led Kabul back in 1996, could not seek support from the Pashtun leaders as well. The restrictive policies of the Taliban created an opposing force under the leadership of the Pashtun Mujahideens. The 21st century saw a global consensus against the possibility of the Taliban taking over entire Afghanistan. The emergence of ethnic cleansing in Kabul, Hazarajat, Mazar-i-Sharif were prime examples of how minority groups like the Tajiks, Hazaras were victimized and persecuted from their homes. The 2001 attack in Washington changed the political climate in Afghanistan, with the United States declaring “a war on terror”. This initially had made the Taliban a redundant force in Afghanistan, with Hamid Karzai being given the administration. The idea was to ensure an ethnically stable and representative government with the creation of democratic institution building.

Twenty years later, with American troops walking out of Afghanistan, and practically inviting the takeover of Afghanistan by the same Taliban begs a larger question. The geopolitical relevance of the takeover has been debated and very much articulated in the past couple of months. But the question that remains is what will the re-emergence of the Taliban mean to the ethnic minorities? Aljazeera reports that there has been a striking increase in violence against the Hazara community yet again. In October 2021 Amnesty came up with a report that around 4000 Hazaras were persecuted from their homes. Mazar –e –Sharif yet again saw episodes of ethnic cleansing. History is repeating not just with respect to communities, but also with respect to locations.

This pattern of violence is parallel to the 1996 takeover, and after 25 years the chain of persecution and violence is again being strung. While we debate the relevance of ethnicity in understanding the Afghan Conflict, the current political climate of Afghanistan has already started being divided under ethnic lines. The cabinets being showcased, with the representation of some non-Pashtun groups – does not rule out the pattern of violence the Taliban comes with. While concluding, one should also observe the legitimacy politics Taliban has been playing through the last decade, where we also witness some Hazara elders coming out and supporting the Taliban rule, as opposed to the previous “foreign power” influenced rule. This version of gaining legitimacy over the years, making it suitable tactics of gaining political mileage in this new Afghanistan is quite unlike of the Taliban. The future of Afghanistan and its ethnic groups is dependent on how soon the international community can unleash checks and balances on this new Taliban-led Afghanistan. This can most likely turn into a civil war-like condition within Afghanistan, unsettling a new round of violence and persecution.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies.

Title image courtesy: https://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/life-style/