Many of the maritime zone legislations enacted decades back were not in harmony with the current needs of the maritime sector. There is a need to revisit and review these legislations.

India, its maritime neighbours, and the majority of coastal States across the globe have realised the great potential that the ocean resources hold towards propelling their national economy’s inter-alia, participated in the deliberation and development of the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Seas 1982 (UNCLOS 1982), for a maritime zone-based rights system.

Towards this end, Parties to UNCLOS 1982 adopted various national legislations to amalgamate the UNCLOS 1982 provisions in their respective domestic legal systems to safeguard their interests. The Maritime Zones of India Act of 1976 was India’s initiative toward regulating its own maritime zones. Similar legislations were enacted by India’s maritime neighbours around Mid-1970, even prior to the finalisation and opening up of UNCLOS 1982 for signatures.

Practices of States has since the formulation of UNCLOS 1982 evolved greatly and reshaped its interpretation by nations across the world. And in the past decade, there is a visible wave of amendments/ changes in the region by the majority of India’s maritime neighbours in a bid to exercise stricter control over their respective maritime zones.

Bangladesh has led the initiative of amendments by enacting major amendments to its 1974 Territorial Waters and Maritime Zones Act in 2021. The latest amendments provide definitions of a few key terms such as Military Survey, Continental Margin, Geodesic, and Installations. It also goes on to highlight provisions in respect of ‘Remotely Operated Underwater Vehicle (ROV)’, ‘Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV)’, and ‘Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (UUV)’.

Another unique provision in Bangladesh’s new amendment is its formalisation of policies, work plan, and implementation of economic activities by legislating the concept of a Blue Economy and Ocean Governance. The provision should provide legislative backing to Govt initiatives in the maritime sector. Another change reflected in the new amendment is the change in its stance, whereby Bangladesh earlier required prior permission from all foreign warships for passing through its Territorial Sea. The said condition has now been shifted to ‘prior notice’ and is reflected in its 2021 amendment.

The latest entrant to this initiative of amendments to maritime zone legislation is Pakistan. It enacted its new Maritime Zones Act in early Feb 2023 and repealed the 1976 legislation. Apart from the commonality of provisions retained in the new legislation, a few unique measures have been incorporated. In addition to governing the Security, Customs, Immigration, Sanitary, and Fiscal issues in Pakistan’s Contiguous Zone, the provision for regulating archaeological and historical objects has been added. This initiative appears to have been derived from Article 8 of the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage.

Apart from the same, Pakistan’s new legislation has incorporated provisions regulating marine pollution and dumping based on various international instruments. It incorporates provisions empowering officers of the Pakistan Navy and Pakistan Maritime Security Agency and also penalises various offences such as armed robbery at sea and piracy. It also recognises the concept of a safety zone (500 meters) and the right of hot pursuit as provided in UNCLOS 1982.

Myanmar also adopted a new Myanmar Territorial Sea and Maritime Zone Law in 2017 and repealed its earlier 1977 legislation. Noteworthy additions under the new law are the incorporation of the ‘Right of Hot Pursuit’ and specific mention of the coordinates of the sea boundary line demarcated between India and Myanmar under the 1986 agreement.

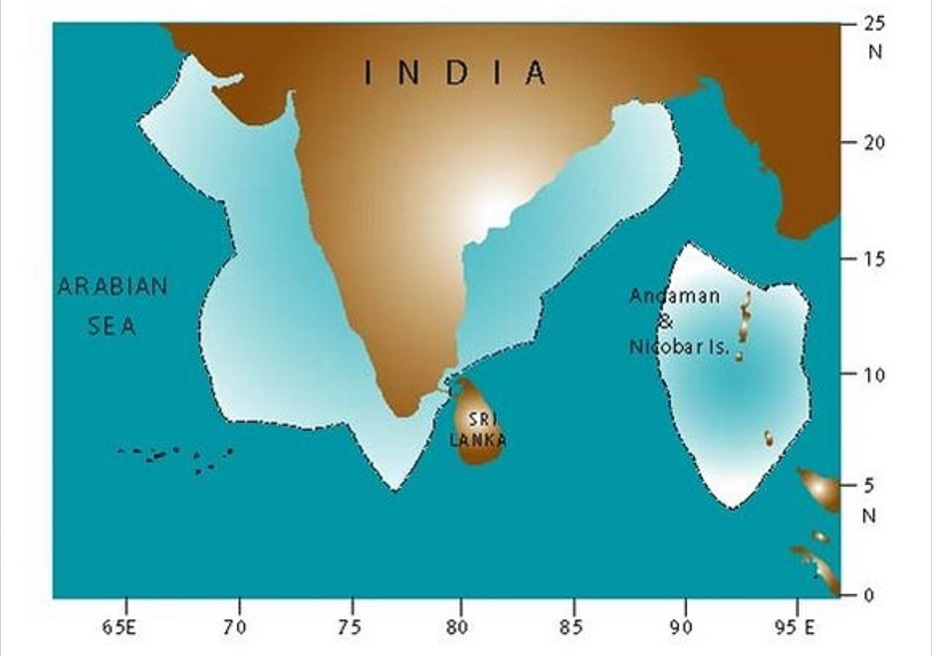

With India as an emerging power and gaining a position amongst the top five economies in the world, regulation of the maritime sector is a key focus area. Legislation and framing of domestic policies continue to remain a thrust area for developing and safeguarding Indian interests in the maritime sector. India’s maritime stance on various issues is similar to its nearby maritime neighbours like Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan, Maldives, and Sri Lanka.

With these nations in the region reshaping their maritime legislations, the need for robust and comprehensive maritime legislation that is ahead of current trends and able to cater to future developments is paramount. India’s legislative restructuring may accordingly require rethinking for enacting future-ready maritime legislation. The legislation needs to cater to the requirements of the emerging trends and also match India’s global stature, so as to reinforce it as an emerging leader not only in the economic arena but also in the field of development of the legislative framework.

Title image courtesy: Quora

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies