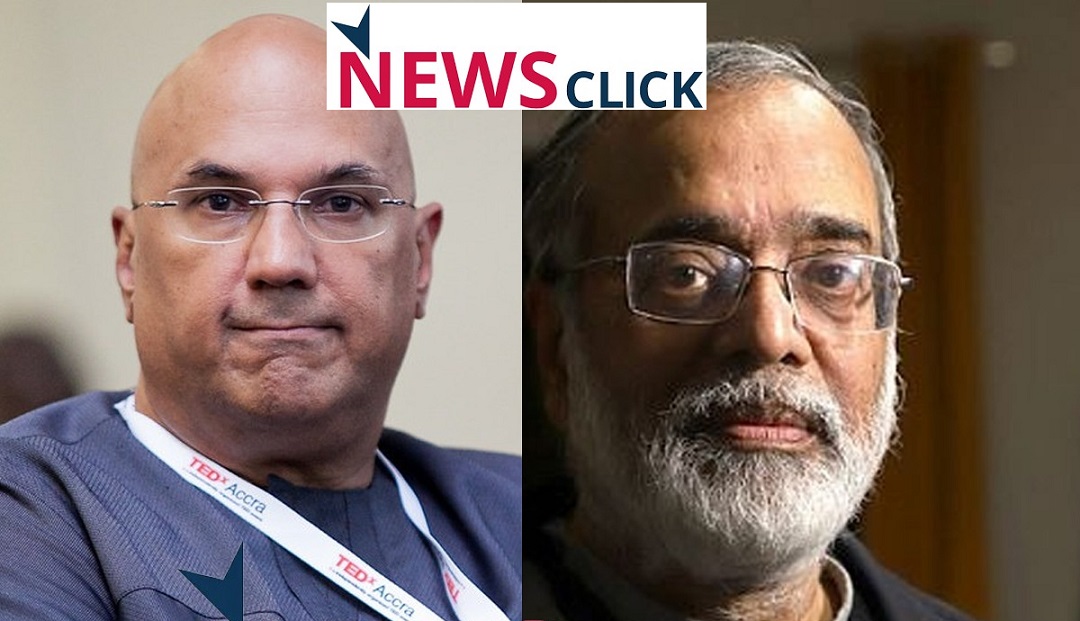

Attracted by the slogans of socialism and the creation of an egalitarian society free from exploitation and suppression, sections of political leaders, youth, intellectuals, academics and media personnel develop pro-China sentiments. In many instances, they operate as ‘proxy soldiers’ in defending China at national and international levels, often hurting India’s national interests. The New York Times has recently brought out a sensational investigative story on the global Chinese propaganda and the interlinkages of a network of activists- groups, non-profit organisations and shell companies in such operations. At the heart of this network is an American millionaire, Neville Roy Singham, a pro-left businessman having close links with the propaganda arm of the Communist Party of China (CPC). The New York Times highlighted that ‘In New Delhi, corporate filings showed, Mr Singham’s network had financed a news site, NewsClick, that sprinkled its coverage with Chinese government talking points’. It may be recalled that in 2021, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) investigated the alleged Chinese links to the NewsClick and the fraudulent infusion of Rs 38.05 crore during 2018-21. The NewsClick which was initially started as a social media site in early 2009 was incorporated as a registered company (PPK Newsclick Studio Pvt. Ltd.) on January 11, 2018, by Prabir Purkayastha, as an online news portal covering both Indian and international news. In the wake of the New York Times revelations, the ED has stepped up its investigations including the attachment of assets and properties of Purkayastha in New Delhi, worth many crores. The agency is likely to quiz certain political leaders and left intellectuals who were in touch with or had frequent digital communication with Neville Roy Singham.

The New York Times story unfolds China’s innovative techniques for pushing pro-China narratives at the international level so as to deflect international criticism of its hegemonistic designs or abuses of human rights. China, according to the Times story, used a ‘global ecosystem of activists and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to build a network that subtly promotes the Chinese nation and parrots the government’s stance’. These groups ‘echo one another and are echoed in turn by the Chinese state media’. ‘Thoughtworks’, a Chicago-based IT consulting firm founded by Singham in the 1980s played a crucial role in floating these networks of non-profit bodies and in channelising huge funds for pro-China propaganda and campaigns across the world. Some of these non-profit organisations run by pro-left activists in the US have ties to Neville Singham’s network through domain registration records, etc. in order to scuttle the mandatory registration and other procedures under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (of the US). Notable among them is ‘No Cold War’ which was at the forefront of vituperative attacks from the West for its rhetoric against China that has made it distancing from issues like climate change and racial injustice. Another outfit was ‘Code Pink’ formed at the instance of Singham’s wife, Jodie Evans. Once a strident critic of China’s authoritarian regime, Code Pink has now become a blind supporter of China, praising it as a ‘defender of the oppressed and a model for economic growth without slavery or war’. On many geopolitical issues such as the China-Taiwan conflict, the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, Covid vaccine diplomacy, human rights violations of Uyghur rebels, etc., ‘Code Pink’ operated like a mouthpiece of Chinese media. Elated by such blanket support, the Chinese state media had liberally retweeted the posts/tweets of bodies like ‘Cold Pink’ and ‘No Cold War’ across the world obviously to galvanise international opinion in China’s favour.

Of course, the ‘propaganda game’ or ‘lobbying’ is not a new phenomenon in international politics or power struggles among the comity of nations. During the cold war era, both the Soviet Union and the US and their allies went to great lengths to portray the virtues of the good life offered by their socio-economic system and to reveal the alleged deficiencies of their rivals’ systems. In many instances, truth or hard realities were suppressed, instead, rosy pictures of affluence and development were presented with much rhetoric and fanfare to attract the nations to their alliance or blocs. But power equations had drastically changed after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the sporadic geopolitical developments that had virtually changed the complexion and polity of many East European countries. An interrelated development was the emergence of China as a major power with global ambitions to surpass the US as a superpower.

Though the evolution of China’s sprawling propaganda system can be traced to the post-1978 reform era, the country has fully geared up its propaganda machine in the present millennium, greatly influenced by such geopolitical factors. The negative image of China by virtue of its ‘closed-door policies’ for many decades and blatant negation of international conventions and protocols on issues of common concern and interest for humanity has hindered the international acceptance of its rise as a global great power. Thus, one of the priority tasks of the CPC was to “gain face” (‘yao mianzi’) in the international arena, for which it has adopted various strategies and mechanisms – both traditional and modern – with heavy investment, ‘ranging from US$7 billion to $10 billion’, (Ann Marie Brady, ‘China’s Propaganda Machine’- Wilson Centre- October 26, 2015).

In the formulation of an aggressive pro-China propaganda strategy, Xi Jinping played a pivotal role. In his address at the national meeting on Propaganda and Theoretical work in April 2013, Xi underlined; ‘We should enhance our foreign-oriented publicity work through trying methods and with new concepts, domains and expressions that are understood by both China and the rest of the world, telling the story of our country and making our voice heard’. Later in 2014, while addressing the party’s Politburo, he pushed his agenda holding that China should be portrayed as a civilised country featuring a rich history, ethnic unity, and cultural diversity, and as an Eastern power with good government, a developed economy, cultural prosperity, national unity, and beautiful scenery. He further highlighted that China should also be projected as a responsible country that advocates peace and development, safeguards international fairness and justice, makes a positive contribution to humanity, and as a socialist country that is open and friendly to the world, full of hope and vitality. With such announcements and concerted moves, China’s foreign propaganda efforts have taken on a new level of assertiveness, confidence, and ambition with several new themes and slogans such as “tell a good Chinese story”, “Chinese Dream,” and “rich country, strong military.” etc., etc.

Definitely, the Chinese leadership has certain advantages to effectively pursue its global propaganda agenda. First and foremost is China’s significant advances in cyberspace and interrelated new technologies that transcend beyond countries and continents. As rightly pointed out by Kerry Allen, China media analyst of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), ‘with more than one billion internet users, China certainly has the capability to orchestrate large-scale social media campaigns, and target what it sees as anti-China voices with a wealth of opposing opinions’. Moreover, the sprawling network of hackers and fake social media profiles are pushing pro-China narratives with a view to discrediting those seen as opponents of China’s government. Their main aim is to delegitimise the West and augment China’s influence and image overseas. The ‘Dragon Bridge’ (‘Spamouflage Dragon’) channel which has been engaged in systematic US-bashing is at the forefront of posting narratives praising China’s pandemic response, criticism of pro-democracy protests, and more strident support for unification with Taiwan. Secondly, China could effectively disseminate the theme of economic cooperation and development across the world through its ambitious projects such as the New Silk Road initiative that go ‘beyond ideology’. They propagate that these projects aimed at setting new norms in international relations will not only help to put an end to the exploitation of weaker states by the affluent countries but also all other political and economic equalities of the old order. Thirdly, with a wide network of cultural and other bodies such as the Confucius Institutes, Chinese cultural centres, acupuncture establishments, etc., they could promote pro-China sentiments and traditional Chinese culture to a larger global audience.

Among the diverse methods adopted by China in its global propaganda endeavours, two established approaches are the cultivation of prominent personalities in different countries to promote the Chinese line and the borrowing/acquisition of foreign electronic and print media. The Chinese leaders or diplomats develop symbiotic relationships or partnerships with highly prominent foreign figures with pro-China proclivities and use them in different fields to promote Chinese interests. Almost all countries have such ‘friends of China ‘. In this connection, many ‘China watchers’ cite the examples of former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger or former British prime minister Tony Blair. The Chinese government or the Party extends invitations to such ‘friends’ or their delegations for visiting the country as part of familiarisation of China and the Chinese way of life. Very often, these personalities subsequently become the ‘virtual ambassadors’ of China by promoting the interests of the country. In the case of borrowing media, the official Chinese propaganda network establishes good rapport with reputed foreign journalists, channel promoters, prominent ‘think tanks’ and intellectuals who are politically or ideologically friendly to China. The Chinese propagandists use their services for publishing pro-China articles in leading foreign newspapers or telecasting programs through popular foreign channels or networks.

Against this backdrop, the NewsClick controversy assumes considerable significance in the context of India-China relations. Ever since the China-India conflict in 1962, the relations between the two countries remained strained, if not hostile with occasional skirmishes as happened in the recent past in Doklam or the Galwan valley. Moreover, the border disputes remain alive with China’s refusal to accept the Line of Actual Control and her occupation of vast areas of Indian territory. On many occasions, the CPC and its propaganda set-up tried to build up a pro-China lobby within India and outside by extending tacit support to groups or movements which raised revolutionary slogans or ‘sub-nationalist struggles’ challenging the sovereignty and territorial integrity of India. A historical example was the Naxalbari uprisings of the late 1960s. Describing the movement as ‘Spring Thunder over India’, the CPC and the Chinese media glorified it as a ‘historic turning point in the Indian revolution’ just along the lines of the Chinese revolution. Ironically, many left-wing extremist groups look towards Beijing for guidance and moral support. Attracted by the slogans of socialism and the creation of an egalitarian society free from exploitation and suppression, sections of political leaders, youth, intellectuals, academics, and media personnel declared solidarity with such movements and developed pro-China sentiments. In many instances, they operate as ‘proxy soldiers’ in defending China at national and international levels, even jeopardising Indian interests. Globalisation and the spread of new technology have given added leverage to them to fan out such propaganda using social media and other electronic channels. The threat emanating from such organised activities has grave national security implications. Unfortunately, sections of political leaders or policymakers fail to visualise such developments from the right perspective. For example, in the NewsClick controversy, certain leaders instead of nailing the actual perpetrators of the alleged deal, resorted to political rhetoric and mud-slinging undermining the gravity of the threat. So long as Indo-China relations remain strained, we should monitor such issues with an eagle eye so that our national interests would be fully protected.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of India and Defence Research and Studies

Article Courtesy: Asian Institute for China and IOR Studies (AICIS)